![]()

CHAPTER 1

Health in a changing world

INTRODUCTION

Public health is about protecting and improving the health of whole populations and communities. Its motivation is to improve the health of individual people. But unlike clinical medicine, which focuses on people one at a time, public health takes a broader focus to understand and engage with the many factors (societal, behavioural and environmental) that promote or undermine health.

Public health emphasizes the promotion of health and the prevention of disease and disability; the collection and use of epidemiological data; population surveillance and other forms of empirical quantitative assessment; a recognition of the multidimensional nature of the determinants of health; and developing effective solutions to population health problems. Any list of activities and projects carried out by a department of public health would be lengthy and diverse and not necessarily consistent with a similar list produced by another department in the same country or in a different country. That is why perusing such lists or reading and talking about public health programmes often gives a better and clearer understanding of what public health is about than memorizing a formal definition.

Public health practice can involve tackling huge issues that affect the whole world, such as the health effects of climate change, as well as quite circumscribed and small-scale interventions, such as introducing new hygiene procedures at a local children’s animal petting farm after an outbreak of serious illness caused by the bacterium Escherichia coli O157.

While most of the core concepts of public health have remained the same for many decades, there have been three big shifts of emphasis from the late twentieth century into the twenty-first century. First, the paradigm of public health is no longer national; it is global. Second, public health is no longer only the domain of professionals. Health system managers and political leaders have had to become engaged in order to address the challenges of new threats to health and the growing burden of potentially preventable, non-communicable diseases. Third, pursuing effective solutions for problems that are mainly multifactorial in causation and influenced by broader environmental, social and economic conditions requires interdisciplinary practice and multi-agency, multisector cooperative working. A simple medical model of intervention is not in keeping with a modern public health approach. This is emphasized throughout the book.

WHAT IS HEALTH?

The question ‘What is health?’ is not an easy one to answer. United Nations officials had to ponder it when, in 1948, they founded the World Health Organization (WHO). They came up with the following: ‘Health is a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’, a definition that has been widely cited ever since.

Many people do think of health, primarily, as the absence of disease. Diagnosing and treating disease is the central focus of most health systems, and at the core of traditional medical school curricula. Tackling disease is seen as the primary route to improving health – and there has been considerable success in doing so. In many parts of the world, including the United Kingdom, other government action to improve health has been far less convincing, and healthcare systems continue to focus on the absence of disease, rather than taking the more holistic view that the World Health Organization’s definition suggests. For example, in the Conservative government’s financial statement in the autumn of 2015, despite the need to find funds to pay down a deficit, a major increase was made in funding for the National Health Service (NHS), largely to address pressures in hospital services, while public health budgets were cut. In the late 1960s, the leading British public health thinker Thomas McKeown of Birmingham said, ‘The disposal of society’s investment in health is based on strange premises. It is assumed that we are ill and made well, whereas it is nearer to the truth that we are well and made ill’. Fifty years on, it is difficult to dispute the continuing validity of this telling observation when the policies of many health ministries are viewed in the cold light of day.

In the mid-1980s, the World Health Organization published the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. It followed the first major global conference to address the concept of health promotion, which is now a mainstream component of public health. The Ottawa Charter developed the idea of health as a fundamental human right, and identified a number of prerequisites for it, including:

- Peace

- Food

- Shelter

- Education

- Income

- Sustainable resources

- A sustainable ecosystem

- Social justice and equity

The Ottawa Charter saw it as more helpful to define the social and physical resources required for health and focus on improving those, rather than defining health at the individual level.

The original World Health Organization definition of health is more than half a century old. Some see its statement that health is a state of complete well-being as unhelpful. Very few people are completely well in every way, and on a pedantic view of the definition, most people are therefore unhealthy. As people age, many begin to accumulate chronic, non-communicable diseases. Arguably, a more helpful definition would not write them all off as failing to attain ‘a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being’. The World Health Organization’s original definition also says nothing about what physical, social or mental well-being means, simply stating that health requires each of these to be ‘complete’. Some maintain that the definition has led to an ideal of perfect health, and that this utopian notion has fed an increasing medicalization of society’s problems.

Today, while the World Health Organization still cites its original definition, it also discusses health in much broader terms. On a glance through its publications, the reader will see phrases linked to the concept of health like ‘a resource for everyday living’, ‘a fundamental human right’, and ‘an essential component of development’.

There is a widespread consensus among international agencies, including the World Health Organization, that the concept of health, the influences on it and the language used to debate it should indeed be very broad, with strong links to economic and social development and – particularly in the poorer countries of the world – to gender and poverty.

Different cultures view health differently. For example, First Nation people in Australia and Canada think of well-being as more important than the absence of disease. Health is a balance of spiritual, emotional and physical factors, rooted in the traditions and culture of the community and connected to the spirit of the land and to nature. Traditional Chinese medicine focuses on maintaining harmony (between the two forces of yin and yang). People are healthy when there is harmony between body and mind, and the aim of healing is to restore this harmony when it has become disturbed.

In the West, the definition of health continues to be debated. This is not an esoteric activity, since one of the reasons for defining it is to move to the practical task of measuring it. Most so-called ‘measures’ of health are not explicitly linked to a definition of health, but rather describe an aspect of an implied definition. Some traditional measures are less valuable than they once were, for example, mortality rates in countries with prolonged expectation of life. At the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development convened a conference of Dutch and international health experts, aiming to redefine health. The thrust of the meeting, to challenge the time-served World Health Organization definition, was captured in the title: Health – A State or an Ability? Towards a Dynamic Concept of Health. This conference did not conclude with an agreed, revised, new definition of health, but it did reveal the complexity of trying to do so and the multiple ways through which a definition could be arrived at. It was a deep and searching analysis of what health means and how it could be formally defined. Some of the key conclusions were:

- Health should not be considered a consistent ‘state’, but is dynamic, and is related both to the equilibrium of different aspects and to age.

- Characteristics of health include an inner resource, a capacity, an ability and a potential to cope with or adapt to internal and external challenges (resilience); to perform (relative to potential, aspirations and values); to achieve individual fulfilment; to live, function and participate in a social environment; and to reach a high level of well-being, even without nutritional abundance or physical comfort.

- Health should be considered in an individual and group context; social inequalities have a major influence on health.

- Operationalizing the concept of health is necessary for measurement purposes, to provide an evidence base for policies and interventions, and to enable appropriate evaluations.

- The individual’s capacity for self-management, participation, empowerment and resilience is of major importance, and should be stimulated and trained.

Both the Ottawa Charter and the Netherlands expert meeting brought out a much rounder view of health than is currently the mainstream concept in much of the Western world. These, and other challenges to the established Western paradigm of health, emphasize two things in particular: health as a positive concept to be strived towards, not simply the absence of disease, and the importance of mental and social health, not just physical health.

Another strand of twenty-first century thinking on health encompasses the concepts of well-being, quality of life and happiness. Each of these is as complex and argued about as health itself. Happiness is the subject of a growing academic literature. The World Happiness Report, written by British social scientist Richard Layard and others, sets out the case for making population happiness the central aim of government. It argues that society’s aim should be to maximize the happiness of its members. Judging the success of a country on factors other than economic prosperity is not a new idea. In 1968, Robert F. Kennedy (1925–1968), then a presidential candidate in the United States, raised the thought-provoking idea of an entirely differently constructed measure of nationhood. He said:

The gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.

This theme has been developed and recast in the twenty-first century. In Bhutan, the government’s key measure of success is not gross national product but gross national happiness. Bhutan measures gross national happiness using a multipart index (psychological well-being, time use, community vitality, cultural diversity, ecological resilience, living standard, health, education and good governance). Just under half of its population is happy (8% are deeply happy and 33% extensively happy). The remainder is classed as ‘not yet happy’, and the government’s aim is to understand and address the reasons why.

No country uses a direct measure of health as one of its central guiding measures.

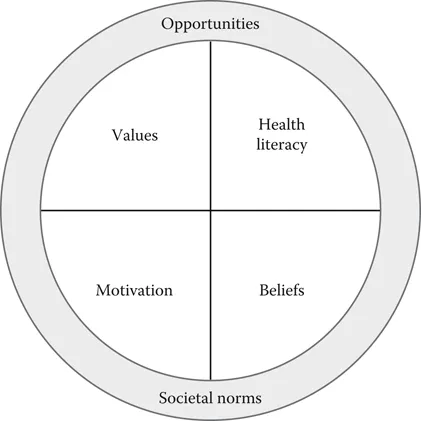

Much of the political debate about health is rather superficial. Words like behaviour are bandied around to explain why some people develop conditions like obesity. There are several different determinants of behaviour, which are complex in their dimensions: an individual’s level of understanding about risks to health, their beliefs, whether they hold the attainment of good health as a fundamental value, and self-control. In turn, all these strands, and the way that they interact, are shaped by the opportunities and the availability of the means to secure good health in the country, city, town and small community in which they live. They are also profoundly influenced by the culture and norms of their country and social group (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Determinants of health behaviour at the individual level.

PUBLIC HEALTH

When a formal definition of public health is required, two tend to be quoted. The first was formulated in 1920 by Charles-Edward Amory Winslow (1877–1957), the founding chairman of the Department of Public Health at Yale University. He defined public health as ‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society, organizations, public and private, communities and individuals’.

Winslow was a bacteriologist by training, so his definition of public health seems remarkable in being so broad based and holistic. It was so modern in its orientation that when Sir Donald Acheson (1926–2010), England’s chief medical officer, reviewed the public health function in 1988, he defined public health in a way that deviated little from Winslow’s – although it was briefer. Acheson’s definition tends to be the version more often cited in the United Kingdom: ‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organized efforts of society’.

Since the 1970s, there has been an increasing emphasis on framing strategies aimed at promoting or improving public health. Governments of countries, international organizations like the World Health Organization and professional ...