![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

Contemporary Theoretical Debate in Archaeology

Ian Hodder

Any archaeology student is today faced with a large number of volumes dealing with archaeological theory, whether these be introductory texts (e.g. Johnson 2010), historical surveys (Trigger 2006), readers (Preucel and Mrozowski 2010; Whitley 1998), edited global surveys (Hodder 1991; Meskell and Preucel 2004; Ucko 1995), or innovative volumes pushing in new directions (e.g. Schiffer 1995; Shanks and Tilley 1987; Skibo et al. 1995; Tilley 1994; Thomas 1996, etc.). It has become possible to exist in archaeology largely as a theory specialist, and many advertised lecturing jobs now refer to theory teaching and research. Regular conferences are devoted entirely to theory as in the British or USA or Nordic TAGs (Theoretical Archaeology Group). This rise to prominence of self-conscious archaeological theory can probably be traced back to the New Archaeology of the 1960s and 1970s.

The reasons for the proliferation of theory texts are numerous, and we can probably distinguish reasons internal and external to the discipline, although in practice the two sets of reasons are interconnected. As for the internal reasons, the development of archaeological theory is certainly very much linked to the emphasis in the New Archaeology on a critical approach to method and theory. This self-conscious awareness of the need for theoretical discussion is perhaps most clearly seen in Clarke’s (1973) description of a loss of archaeological innocence, and in Binford’s (1977) call “for theory building.” Postprocessual archaeology took this reflexivity and theorizing still further. Much of the critique of processual archaeology was about theory rather than method, and the main emphasis was on opening archaeology to a broader range of theoretical positions, particularly those in the historical and social sciences. In fact, anthropology in the United States had already taken its historical and linguistic “turns,” but it was only a view of anthropology as evolution and cultural ecology that the New Archaeologists had embraced. When the same “turns” were taken in archaeology to produce postprocessual archaeology, the theorizing became very abstract and specialized, although such abstraction was also found in other developments, such as the application of catastrophe theory (Renfrew and Cooke 1979). In fact all the competing theories have developed their own specialized jargons and have a tendency to be difficult to penetrate.

One of the internal moves was towards a search for external ideas, and external legitimation for theoretical moves within archaeology. There has been a catching up with other disciplines and an integration of debate. Similar moves towards an opening and integration of debate are seen across the humanities and social sciences. There are numerous examples of close external relations between archaeology and other disciplines in this book. Shennan (chapter 2) describes the productive results of interactions between biology, population demography and archaeology. Human behavioral ecology (Bird and O’Connell, chapter 3) is closely tied to ecology and evolutionary ecology. Discussion of complex systems in archaeology is part of wider debates in cybernetics and systems theory (Kohler, chapter 5). Renfrew (chapter 6) describes debates with cognitive science and evolutionary psychology. Barrett (chapter 7) shows how the agency debate in archaeology owes much to sociology. Thomas (chapter 8) demonstrates that archaeological work on landscapes has been greatly influenced by geography, especially by the recent cultural geographers, and by art history and philosophy. Socio-cultural anthropology is a key partner in the debates described in chapters 7 to 13, and science and technology studies have greatly influenced archaeological discussions of symmetry (Olsen, chapter 10) and materiality (Knappett, chapter 9). History and the history of art are central to many of the chapters in the latter part of this book, especially the work on visualization (Moser, chapter 14). But it should be pointed out that these interactions with other disciplines are not seen as borrowing from a position of inferiority. Increasingly the particular nature of archaeological data, especially their materiality and long-term character, is recognized as having something to offer other disciplines in return.

Gosden (chapter 12) points out the need for archaeologists to engage with post-colonial theory. The critique from other voices and from multiple non-western interests has often forced theoretical debate (Colwell-Chanthaphonh, chapter 13). For example, Norwegian archaeology saw a long theoretical debate about the abilities of archaeologists to identify past ethnic groups as a result of Sami–Norwegian conflicts over origins. Reburial issues have forced some to rethink the use of oral traditions in North American archaeology (Anyon et al. 1996). Indigenous groups in their claims for rights question the value of “objective science” (Langford 1983). A similar point can be made about the impact of feminism. This has questioned how we do research (Gero 1996) and has sought alternative ways of writing about the past (Spector 1994), opening up debate about fundamentals. The same can also be said of debates about representation in cultural heritage and museums (see Moser in chapter 14; Merriman 1991). These debates force a critique of interpretation. They challenge us to evaluate in whose interests interpretation lies, and to be sensitive to the relationship between audience and message.

The community of discourses model

It can be argued that archaeology has a new maturity in that, as claimed above, it has caught up with disciplines in related fields in terms of the theories and issues being discussed. Many now, as we will see in this book, wish to contribute back from archaeology to other disciplines – this emphasis on contributing rather than borrowing suggests a maturity and confidence which I will examine again below. This maturity also seems to involve accepting diversity and difference of perspective within the discipline.

There are always those who will claim that archaeology should speak with a unified voice, or who feel that disagreement within the ranks undermines the abilities of archaeologists to contribute to other disciplines or be taken seriously. A tendency towards identifying some overarching unity in the discipline can be seen in some of the chapters in this volume. Renfrew (1994) has talked of reaching an accommodation between processual and postprocessual archaeology in cognitive processual archaeology. Kohler (chapter 5) suggests that current approaches to complex systems incorporate critiques of a simple positivism, and he refers to Bintliff’s (2008) argument that complexity theory integrates culture historical, processual, and postprocessual perspectives. Several authors over the past two decades have argued for some blending of processual and postprocessual approaches (e.g. Hegmon 2003; Pauketat 2001; Wylie 1989) though not without critique (Moss 2005).

There is often an implicit assumption in discussions about the need for unity in the discipline that real maturity, as glimpsed in the natural sciences, means unity. But in fact, Galison (1997) has argued that physics, for example, is far from a unified whole. Rather he sees it as a trading zone between competing perspectives, instrumental methods, and experiments. In archaeology, too, there is a massive fragmentation of the discipline, with those working on, say, Bronze Age studies in Europe often having little in common with Palaeolithic lithic specialists. New Archaeological theories were introduced at about the same time as, but separate from, computers and statistics, as the early work of Clarke (1970) and Doran and Hodson (1975) shows. Single-context recording (Barker 1982) was introduced to deal with large-scale urban excavation, and was not immediately linked to any particular theoretical position. And so on. In these examples we see that theory, method, and practice are not linked in unified wholes. While the links between domains certainly exist, the history of the discipline is one of interactions between separate domains, often with their own specialist languages, own conferences and journals, and own personnel. As Galison (1997) argues for physics, it is this diversity and the linkages within the dispersion which ensure the vitality of the discipline.

We should not then bemoan theoretical diversity in the discipline. Diversity at the current scale may be fairly new in theoretical domains, but it is not new in the discipline as a whole. These productive tensions are important for the discipline as a whole. We should perhaps expect periods of to and fro as regards diversity and unity. Marxist, critical, and feminist archaeologists (Conkey 2003; Leone and Potter 1988; McGuire 1992; Patterson 1994) provide examples of the ways in which important movements in archaeology get incorporated over time into the mainstream. Each of these approaches, fundamental struts of contemporary debate in archaeology, have for many archaeologists now become integrated into all aspects of their work, forming part of the currency of intellectual exchange. And yet at the same time, new tensions and divisions emerge (e.g. Shennan 2002 or Watkins 2003) to create new forms of diversity.

From “theory” to “theory of”

The partial disjunction between theoretical and other domains identified above, as well as the specialization and diversification of theoretical positions, has reinforced the view that there can be something abstract called “archaeological theory,” however diverse that might be. For many, archaeological theory has become rarified and removed. In this abstract world, apparently divorced from any site of production of archaeological knowledge, theoretical debate becomes focused on terms, principles, basic ideas, universals. Theoretical debate becomes by nature confrontational because terms are defined and fought over in the abstract. The boundaries around definitions are policed. Abstract theory for theory’s sake becomes engaged in battles over opposing abstract assertions. Theoretical issues very quickly become a matter of who can “shout the loudest,” of “who sets the agenda?” (Yoffee and Sherratt 1993).

But in practice we see that the abstract theories are not divorced from particular domains at all. Rather, particular theories seem to be favored by certain sets of interests and seem to be related to questions of different types and scales. Thus evolutionary perspectives have been most common in hunter-gatherer or Palaeolithic studies; gender studies have had less impact on the Palaeolithic than on later periods; human behavioral ecology tends to be applied to hunter-gatherers or societies with simple systems; power and ideology theories come into their own mainly in complex societies; and phenomenology seems to be particularly applied to prehistoric monuments and landscapes.

When archaeologists talk of a behavioral or a cognitive archaeology, they tend to have specific questions and problems in mind. For Merleau-Ponty (1962), thought is always “of something.” In this book, Thomas (chapter 8) describes how for Heidegger place is always “of something.” So too, archaeological theory is always “of something.” Theory is, like digging, a “doing.” It is a practice or praxis (Hodder 1992). Post-colonial and Indigenous archaeologies (Gosden, chapter 12, and Colwell-Chanthaphonh, 13) have come about as part of a critical and socio-political movement. Much contemporary social archaeology and heritage theory deals with issues such as reconciliation and healing (Meskell, chapter 11). This practical engagement undermines claims for a universality and unity of archaeological theory.

Of course, it can be argued that archaeology as a whole is engaged in a unified praxis, a unified doing, so that we should expect unified theories. But even at the most general theoretical levels, archaeologists are involved in quite different projects. Some archaeologists wish to make contributions to scientific knowledge, or they might wish to provide knowledge so that people can better understand the world around them. Other archaeologists see themselves in a post-colonial context of multiple stakeholders where a negotiated past seems more relevant. This negotiation may involve accommodation of the idea that past monuments may have a living presence in the world today – that they are “alive” in some sense (Mamani Condori 1989). In the latter context, abstract theory deals less with abstract scientific knowledge and more with specific social values and local frameworks of meaning (see Colwell-Chanthaphonh in chapter 13).

It is in the interests of the academy and of elite universities to promulgate the idea of abstract theory. The specialization of archaeological intellectual debate is thus legitimized. But critique from outside the academy has shown that these abstract theories, too, are embedded in interests – they, too, are “theories of something.” Within the academy, archaeologists vie with each other to come up with yet more theories, especially if they can be claimed to be meta-theories that purport to “explain everything.” In fact, however, this diversity comes from asking different questions – from the diversity of the contexts of production of archaeological knowledge.

Variation in perspective

As a result of such processes, there are radical divergences in the way different authors in this book construe theory. In summary, these differences stem partly from the process of vying for difference, with innovation often influenced by developments in neighboring disciplines. The variation in perspective also derives from the fact that radically different questions are being asked from within quite different sites of production of knowledge.

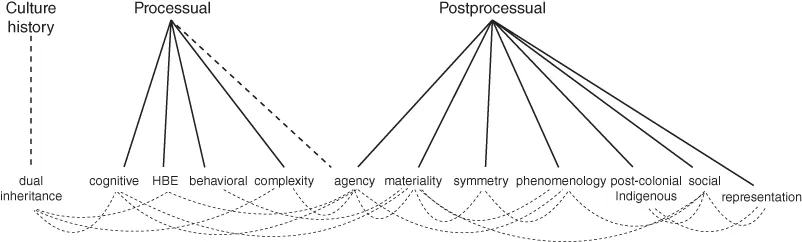

Many of the differences of perspective remain those that have dogged the discipline since the 1980s or earlier. Although there are convergent moments (see below), many of the authors in this volume ally themselves to either processual or postprocessual archaeology. Bird and O’Connell (chapter 3) and LaMotta (chapter 4) argue that human behavioral ecology and behavioral approaches derive from processual archaeology. Both Kohler (chapter 5) and Renfrew (chapter 6) recognize links to postprocessual approaches but draw their main heritage from processual archaeology. Post-colonial archaeology is seen by Gosden (chapter 12) as blending with the postprocessual critique, and Colwell-Chanthaphonh (chapter 13) links Indigenous archaeology partly to the same source. Indeed it is possible to argue that the genealogies of current approaches can be traced to three general perspectives: culture history, processual, and postprocessual as shown in Figure 1.1. Despite some blending and slippage to be discussed below, in origin each theoretical position seems to see itself as largely in one or other of these camps. By culture history I mean approaches in archaeology that are concerned with the descent and affiliation of ceramic and other types through time. The differences between processual and postprocessual archaeology have increasingly become aligned with the wider divisions within contemporary intellectual life between universal rationalism and positivism, on the one hand, and contextual, critical reflexivity, on the other.

The opposition between the two main theoretical camps in archaeology is clearly seen in Schiffer’s account of behavioral archaeology. “Readers may be nonplussed at the absence in the new theory of much vocabulary … such as meaning, sign, symbol, intention, motivation, purpose, goal, attitude, value, belief, norm, function, mind, and culture. Despite herculean efforts in the social sciences to define these often ethnocentric or metaphysical notions, they remain behaviorally problematic and so are superfluous in the present project” (Schiffer 1999: 9). Many approaches in archaeology are less clearly assigna...