![]()

I

Introduction: Approaches to the Problem of Rationality

The rationality of beliefs and actions is a theme usually dealt with in philosophy. One could even say that philosophical thought originates in reflection on the reason embodied in cognition, speech, and action; and reason remains its basic theme.1 From the beginning philosophy has endeavored to explain the world as a whole, the unity in the multiplicity of appearances, with principles to be discovered in reason—and not in communication with a divinity beyond the world nor, strictly speaking, even in returning to the ground of a cosmos encompassing nature and society. Greek thought did not aim at a theology nor at an ethical cosmology, as the great world religions did, but at an ontology. If there is anything common to philosophical theories, it is the intention of thinking being or the unity of the world by way of explicating reason’s experience of itself.

In speaking this way, I am drawing upon the language of modern philosophy. But the philosophical tradition, insofar as it suggests the possibility of a philosophical worldview, has become questionable.2 Philosophy can no longer refer to the whole of the world, of nature, of history, of society, in the sense of a totalizing knowledge. Theoretical surrogates for worldviews have been devalued, not only by the factual advance of empirical science but even more by the reflective consciousness accompanying it. With this consciousness philosophical thought has withdrawn self-critically behind itself; in the question of what it can accomplish with its reflective competence within the framework of scientific conventions, it has become metaphilosophy.3 Its theme has thereby changed, and yet it remains the same. In contemporary philosophy, wherever coherent argumentation has developed around constant thematic cores—in logic and the theory of science, in the theory of language and meaning, in ethics and action theory, even in aesthetics—interest is directed to the formal conditions of rationality in knowing, in reaching understanding through language, and in acting, both in everyday contexts and at the level of methodically organized experience or systematically organized discourse. The theory of argumentation thereby takes on a special significance; to it falls the task of reconstructing the formal-pragmatic presuppositions and conditions of an explicitly rational behavior.

If this diagnosis points in the right direction, if it is true that philosophy in its postmetaphysical, post-Hegelian currents is converging toward the point of a theory of rationality, how can sociology claim any competence for the rationality problematic? We have to bear in mind that philosophical thought, which has surrendered the relation to totality, also loses its self-sufficiency. To the goal of formally analyzing the conditions of rationality, we can tie neither ontological hopes for substantive theories of nature, history, society, and so forth, nor transcendental-philosophical hopes for an aprioristic reconstruction of the equipment of a nonempirical species subject, of consciousness in general. All attempts at discovering ultimate foundations, in which the intentions of First Philosophy live on, have broken down.4 In this situation, the way is opening to a new constellation in the relationship of philosophy and the sciences. As can be seen in the case of the history and philosophy of science, formal explication of the conditions of rationality and empirical analysis of the embodiment and historical development of rationality structures mesh in a peculiar way. Theories of modern empirical science, whether along the lines of logical empiricism, critical rationalism, or constructivism, make a normative and at the same time universalistic claim that is no longer covered by fundamental assumptions of an ontological or transcendental-philosophical nature. This claim can be tested only against the evidence of counterexamples, and it can hold up in the end only if reconstructive theory proves itself capable of distilling internal aspects of the history of science and systematically explaining, in conjunction with empirical analyses, the actual, narratively documented history of science in the context of social development.5 What is true of so complex a configuration of cognitive rationality as modern science holds also for other forms of objective spirit, that is, other embodiments of rationality, be they cognitive and instrumental or moral-practical, perhaps even aesthetic-practical.

Empirically oriented sciences of this kind must, as regards their basic concepts, be laid out in such a way that they can link up with rational reconstructions of meaning constellations and problem solutions.6 Cognitive developmental psychology provides an example of that. In the tradition of Piaget, cognitive development in the narrow sense, as well as socio-cognitive and moral development, are conceptualized as internally reconstructible sequences of stages of competence.7 On the other hand, if the validity claims against which we measure problem solutions, rational-action orientations, learning levels, and the like are reinterpreted in an empiricist fashion and defined away—as they are in behaviorism—processes of embodying rationality structures cannot be interpreted as learning processes in the strict sense, but at best as an increase in adaptive capacities.

Among the social sciences sociology is most likely to link its basic concepts to the rationality problematic. There are historical and substantive reasons for this, as a comparison with other disciplines will show. Political science had to free itself from rational natural law; even modern natural law started from the old-European view that represented society as a politically constituted community integrated through legal norms. The new concepts of bourgeois formal law made it possible to proceed constructively and, from normative points of view, to project the legal-political order as a rational mechanism.8 An empirically oriented political science had to dissociate itself radically from that view. It concerned itself with politics as a societal subsystem and absolved itself of the task of conceiving society as a whole. In opposition to natural-law normativism, it excluded moral-practical questions of legitimacy from scientific consideration, or it treated them as empirical questions about descriptively ascertainable beliefs in legitimacy. It thereby broke off relations to the rationality problematic.

The situation is somewhat different in political economy. In the eighteenth century it entered into competition with rational natural law and brought out the independence of an action system held together through functions and not primarily through norms.9 As political economy, economics still held fast at the start to the relation to society as a whole that is characteristic of crisis theories. It was concerned with questions of how the dynamic of the economic system affected the orders through which society was normatively integrated. Economics as a specialized science has broken off that relation. Now it too concerns itself with the economy as a subsystem of society and absolves itself from questions of legitimacy. From this perspective it can tailor problems of rationality to considerations of economic equilibrium and questions of rational choice.

In contrast, sociology originated as a discipline responsible for the problems that politics and economics pushed to one side on their way to becoming specialized sciences.10 Its theme was the changes in social integration brought about within the structure of old-European societies by the rise of the modern system of national states and by the differentiation of a market-regulated economy. Sociology became the science of crisis par excellence; it concerned itself above all with the anomic aspects of the dissolution of traditional social systems and the development of modern ones.11 Even under these initial conditions, sociology could have confined itself to one subsystem, as the other social sciences did. From the perspective of the history of science, the sociologies of religion and law formed the core of the new discipline in any case.

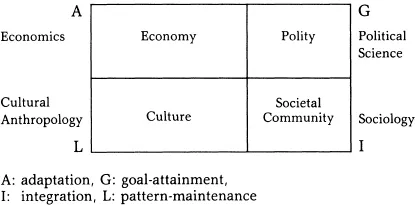

If I may—for illustrative purposes and, for the time being, without further elaboration—refer to the schema of functions proposed by Parsons, the correlations between social-scientific disciplines and subsystems of society readily emerge (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

To be sure, there has been no lack of attempts to make sociology a specialized science for social integration. But it is no accident—rather a symptom—that the great social theorists I shall discuss are fundamentally sociologists. Alone among the disciplines of social science, sociology has retained its relations to problems of society as a whole. Whatever else it has become, it has always remained a theory of society as well. As a result, sociology could not, as other disciplines could, shove aside questions of rationalization, redefine them, or cut them down to small size. As far as I can see, there are two reasons for that.

The first concerns cultural anthropology and sociology equally. The correlation of basic functions with social subsystems conceals the fact that social interactions in the domains important to cultural reproduction, social integration, and socialization are not at all specialized in the same way as interactions in the economic and political domains of action. Both sociology and cultural anthropology are confronted with the whole spectrum of manifestations of social action and not with relatively clear-cut types of action that can be stylized to variants of purposive-rational action with regard to problems of maximizing profit or acquiring and using political power. Both disciplines are concerned with everyday practice in lifeworld contexts and must, therefore, take into account all forms of symbolic interaction. It is not so easy for them to push aside the basic problem of action theory and of interpretation. They encounter structures of a lifeworld that underlie the other subsystems, which are functionally specified in a different way. We shall take up below the question of how the paradigmatic conceptualizations “lifeworld” and “system” relate to one another.12 Here I would like only to stress that the investigation of societal community and culture cannot be as easily detached from the lifeworld paradigm as the investigation of the economic and political subsystems can. That explains the stubborn connection of sociology to the theory of society.

Why it is sociology and not cultural anthropology that has shown a particular willingness to take up the problem of rationality can be understood only if we take into consideration a circumstance mentioned above. Sociology arose as the theory of bourgeois society; to it fell the task of explaining the course of the capitalist modernization of traditional societies and its anomic side effects.13 This problem, a result of the objective historical situation, formed the reference point from which sociology worked out its foundational problems as well. On a metatheoretical level it chose basic concepts that were tailored to the growth of rationality in the modern lifeworld. Almost without exception, the classical figures of sociological thought attempted to lay out their action theory in such a way that its basic categories would capture the most important aspects of the transition from “community” to “society.”14 On a methodological level the problem of gaining access to the object domain of symbolic objects through “understanding” was dealt with correspondingly; understanding rational orientations of action became the reference point for understanding all action orientations.

This connection between (a) the metatheoretical question of a framework for action theory conceived with a view to the rationalizable aspects of action, and (b) the methodological question of a theory of interpretive understanding [Sinnverstehen] that clarifies the internal relation between meaning and validity (between explicating the meaning of a symbolic expression and taking a position on its implicit validity claim), was connected with (c) the empirical question—whether and in what sense the modernization of a society can be described from the standpoint of cultural and societal rationalization. This connection emerged with particular clarity in the work of Max Weber. His hierarchy of concepts of action is designed with an eye to the type of purposive-rational action, so that all other actions can be classified as specific deviations from this type. Weber also analyzes the method of Sinnverstehen in such a way that complex cases can be related to the limit case of understanding purposive-rational action; understanding action that is subjectively oriented to success requires at the same time that it be objectively evaluated as to its correctness (according to standards of Richtigkeitstrationalität). Finally, the connection of these conceptual and methodological decisions with Weber’s central theoretical question—how Occidental rationalism can be explained—is evident.

This connection could, of course, be contingent; it could indicate merely that Weber was personally preoccupied with these problems and that this—from a theoretical point of view— contingent interest affected his theory construction down to its foundations. One has only to detach modernization processes from the concept of rationalization and to view them in other perspectives, so it seems, in order to free the foundations of action theory from connotations of the rationality of action and to free the methodology of interpretive understanding from a problematic intertwining of questions of meaning with questions of validity. Against that, I would like to defend the thesis that there were compelling reasons for Weber to treat the historically contingent question of Occidental rationalism, as well as the question of the meaning of modernity and the question of the causes and side effects of the capitalist modernization of society, from the perspectives of rational action, rational conduct of life, and rationalized worldviews. I want to defend the thesis that there are systematic reasons for the interconnection of the precisely three rationality themes one finds in his work. To put it a different way, any sociology that claims to be a theory of society has to face the problem of rationality simultaneously on the metatheoretical, methodological and empirical levels.

I shall begin (1) with a provisional discussion of the concept of rationality, and then (2) place this concept in the evolutionary perspective of the rise of a modern understanding of the world. After these preliminaries, I shall point out the internal connection between the theory of rationality and social theory: on the one hand, at the metatheoretical level (3) by demonstrating the rationality implications of sociological concepts of action current today; on the other hand, at the methodological level (4) by showing that similar implications follow from approaching the object domain by way of interpretive understanding. This argumentation sketch is meant to demonstrate the need for a theory of communicative action that arises when we want to take up once again, and, in a suitable way, the problematic of societal rationalization, which was largely ousted from professional sociological discussion after Weber.

![]()

1

“Rationality”—A Preliminary Specification

When we use the expression “rational” we suppose that there is a close relation between rationality and knowledge. Our knowledge has a propositional structure; beliefs can be represented in the form of statements. I shall presuppose this concept of knowledge without further clarification, for rationality has less to do with the possession of knowledge than with how speaking and acting subjects acquire and use knowledge. In linguistic utterances knowledge is expressed explicitly; in goal-directed actions an ability, an implicit knowledge is expressed; this know-how can in principle also be transformed into a know-that.1 If we seek the grammatical subjects that go with the predicate expression “rational,” two candidates come to the fore: persons, who have knowledge, can be more or less rational, as can symbolic expressions—linguistic and nonlinguistic, communicative or noncom-municative actions—that embody knowledge. We can call men and women, children and adults, ministers and bus conductors “rational,” but not animals or lilac bushes, mountains, streets, or chairs. We can call apologies, delays, surgical interventions, declarations of war, repairs, construction plans or conference decisions “irrational,” but not a storm, an accident, a lottery win, or an illness.

What does it mean to say that persons behave “rationally” in a certain situation or that their expressions can count as “rational”? Knowledge can be criticized as unreliable. The close relation between knowledge and rationality suggests that the rationality of an expression depends on the reliability of the knowledge embodied in it. Consider two paradigmatic cases: an assertion with which A in a communicative attitude expresses a belief and a goal-directed intervention in the world with which B pursues a specific end. Both embody fallible knowledge; both are attempts that can go wrong. Both expressions, the speech act and the teleological action, can be criticized. A hearer can contest the truth of the assertion made by A; an observer can dispute the anticipated success of the action taken by B. In both cases the critic refers to claims that the subjects necessarily attach to their expressions insofar as the latter are intended as assertions or as goal-directed actions. This necessity is of a conceptual nature. For A does not make an assertion unless he makes a truth claim for the asserted proposition p and therewith indicates his conviction that his statement can, if necessary, be defended. And B does not perform a goal-directed action, that is, he does not want to accomplish an end by it unless he regards the action planned as promising and therewith indicates his conviction that, in the given circumstances, his choice of means can if necessary be explained. As A claims truth for his statement, B claims prospects of success for his plan of action or effectiveness for the rule of action according to which he carries out this plan. To assert this effectiveness is to claim that the means chosen are suited to attain the set goal in the given circumstances. The expected effectiveness of an action stands in internal relation to the truth of the conditional prognoses implied by the plan or rule of action. As truth is related to the existence of states of affairs in the world, effectiveness is related to interventions in the world with whose help states of affairs can be brought into existence. With his assertion, A makes reference to something that in fact occurs in the objective world; with his purposive activity, B makes reference to something that should occur in the objective world. In doing so both raise claims with their symbolic expressions, claims that can be criticized and argued for, that is, grounded. The rationality of their expressions is assessed in light of the internal relations between the semantic content of these expressions, their conditions of validity, and the reasons (which could be provided, if necessary) for the truth of statements or for the effectiveness of actions.

These reflections point in the direction of basing the rationality of an expression on its being susceptible of criticism and grounding: An expression satisfies the precondition for rationality if and insofar as it embodies fallible knowledge and therewith has a relation to the objective world (that is, a relation to the facts) and is open to objective judgment. A judgment can be objective if it is undertaken on the basis of a transsubjective validity claim that has the same meaning for observers and nonparticipants as it has for the acting subject himself. Truth and efficiency are claims of this kind. Thus assertions and goal-directed actions are the more rational the better the claim (to propositional truth or to efficiency) that is connected with them can be defended against criticism. Correspondingly, we use the expression “rational” as a disposition predicate for persons from whom such expressions can be e...