eBook - ePub

The Contemporary Caribbean

Robert B. Potter, David Barker, Thomas Klak, Denis Conway

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 528 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Contemporary Caribbean

Robert B. Potter, David Barker, Thomas Klak, Denis Conway

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This text focuses on the contemporary economic, social, geographical, environmental and political realities of the Caribbean region. Historical aspects of the Caribbean, such as slavery, the plantation system and plantocracy are explored in order to explain the contemporary nature of, and challenges faced by, the Caribbean. The book is divided into three parts, dealing respectively with: the foundations of the Caribbean, rural and urban bases of the contemporary Caribbean, and global restructuring and the Caribbean: industry, tourism and politics.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Contemporary Caribbean un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Contemporary Caribbean de Robert B. Potter, David Barker, Thomas Klak, Denis Conway en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Ciencias físicas y Geografía. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part I

FOUNDATIONS OF THE CARIBBEAN

Chapter 1

CARIBBEAN NATURAL LANDSCAPES

Introduction

At the dawn of the new millennium, the landscapes of the Caribbean region are quite different in appearance from those a thousand years ago. Then, indigenous Amerindian peoples lived throughout the islands and a recent estimate suggests a pre-1492 population of three million (Denevan 1992). Less is known about the pre-Colombian landscapes of the Caribbean islands than those of mainland America, but Sauer’s (1966) discussion of Taino (Island Arawak) raised fields or montones, based on the writing of contemporary Spanish chroniclers, suggests that humanised landscapes, at least in lowland areas of the larger islands like Hispaniola and Cuba, were extensive. Watts (1987) concludes that much of the native mature forests (especially in upland regions) remained intact until the arrival of the Europeans. Over the last 500 years, however, the natural landscapes familiar to Amerindian peoples have largely disappeared and only remnants survive. The impacts of colonisation, commerce, economic development and urbanisation have created new and unique Caribbean cultural landscapes. The transformations have been dramatic, far-reaching and irreversible. Many of these changes are considered in the chapters that follow.

In the new millennium, however, the vestigial natural landscapes have acquired a vibrant significance for Caribbean people. Their importance is epitomised by the marketing of forests, wetlands, flora and fauna in concerted efforts to broaden tourist attractions beyond the traditional nexus of sun, sand and sea (see Chapter 11). But the focus goes far beyond the desire to improve the prospects for tourism. There has been a growing concern for environmental conservation, resource management and cultural heritage, reflected in increasingly active public sector planning agencies and community-based NGOs. The Internet enables planners, environmentalists, educators, media journalists and the general public to exchange ideas and gain access to environmental information in ways inconceivable a generation ago. In recent years there has been a proliferation of useful environmental websites and networking of information resources throughout the region, for individuals and organisations alike (McGregor and Barker 2003).

Two themes underpin the heightened attention given to environmental issues in Caribbean policy debates. The first concerns the omnipresent concept of sustainable development, which has become the main paradigm linking environment, development and human welfare (Potter et al. 2004; Lloyd Evans et al. 1998). Though it is proving an elusive goal for developing countries, sustainable development tries to balance economic growth and social equity with the sustainable use of natural resources. An integral aspect of sustainable development is the wise management of the natural environment. This is particularly relevant to Caribbean islands, which have fragile tropical ecosystems and limited natural resource bases (McGregor and Barker 1995). Agenda 21 forcefully presents the problems of small island developing states [SIDS] as a special case:

Small island developing states, and islands supporting small communities are a special case both for environment and development. They are ecologically fragile and vulnerable. Their small size, limited resources, geographical dispersion and isolation from markets, place them at a disadvantage economically and prevent economies of scale (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, 1992, AGENDA 21:17.123).

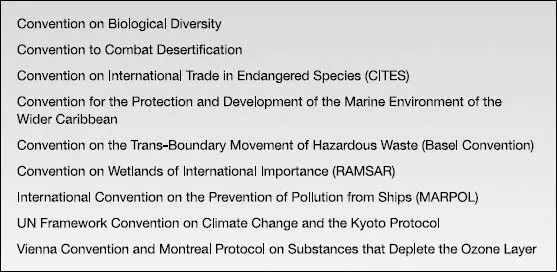

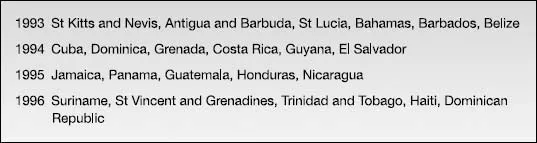

A second theme that links environmental policy issues across the region is the important role of international institutions and conventions, or global governance (Potter et al. 2004). Caribbean nations increasingly operate in this policy arena. When governments become signatories to such international conventions, they assume obligations and commitments to formulate policies and legal mechanisms to implement these written agreements. In return, countries gain access to international financial resources, and scientific and technical advice and cooperation. Figure 1.1(a) lists some international conventions concerning environmental policy that a number of Caribbean governments have signed. One of these, the Convention on Biological Diversity, unveiled at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, had been ratified by most Caribbean nations by the year 2000 (Figure 1.1(b)).

The Convention on Biological Diversity is a good example of how the global community tries to foster sustainable development through environmental conservation. Biodiversity is important because we depend on the huge variety of plants and animals in the world for food, medicine and other raw materials (WRI/IUCN/UNEP 1992). Common sense and the precautionary principle argue for the preservation of all species, so that actual or potentially useful species are not allowed to become extinct, even if we do not know their present value to society or role in natural ecosystems (WCMC 1992). However, the Convention on Biological Diversity clearly acknowledges that conserving biodiversity goes beyond protecting natural landscapes and saving endangered species. It can play a role in achieving sustainable development, and its three objectives are: the conservation of biological diversity; the sustainable use of its components; and fair and equitable sharing of the benefits. A coral reef ecosystem exemplifies the idea that biodiversity (short for biological diversity) has an inherent aesthetic value that people want to see and experience. Healthy coral reefs contribute to species conservation and protect coastal environments, but also provide significant economic and social benefits by promoting tourist activities like diving, snorkelling and trips in glass-bottomed or semi-submersible boats.

Figure 1.1(a) Selected international conventions relating to environmental policy to which some Caribbean nations are signatories

Figure 1.1(b) Ratification of Convention on Biological Diversity

Source: www.biodiv.org/conv

The purpose of this chapter is to explain the formation of Caribbean natural landscapes in the context of their diversity of landforms, ecosystem and species biodiversity, and the conservation of natural landscapes through the establishment national parks and protected areas. We highlight too, in this and subsequent chapters, the environmental impacts of the transformation of natural landscapes through human settlement and economic development. The emphasis is on the insular Caribbean, though we will refer also to the wider Caribbean Basin and territories like Guyana and Belize, which are historically and culturally part of the West Indies. Specifically, the chapter aims to:

• explain how earth-building processes, especially tectonic activity, contribute to the formation and diversity of island landforms;

• explain how denudation processes, such as weathering and erosion, influence island landforms especially with respect to the region’s ubiquitous karst landscapes;

• show how Caribbean climate and terrain influence patterns of natural vegetation;

• explain the significance of Caribbean biodiversity and highlight the need for species and ecosystem conservation;

• explain the linkages between different components of the coastal environment, highlighting the importance of coral reef ecosystems;

• illustrate how national parks and protected areas can be used to protect natural landscapes and contribute to sustainable development.

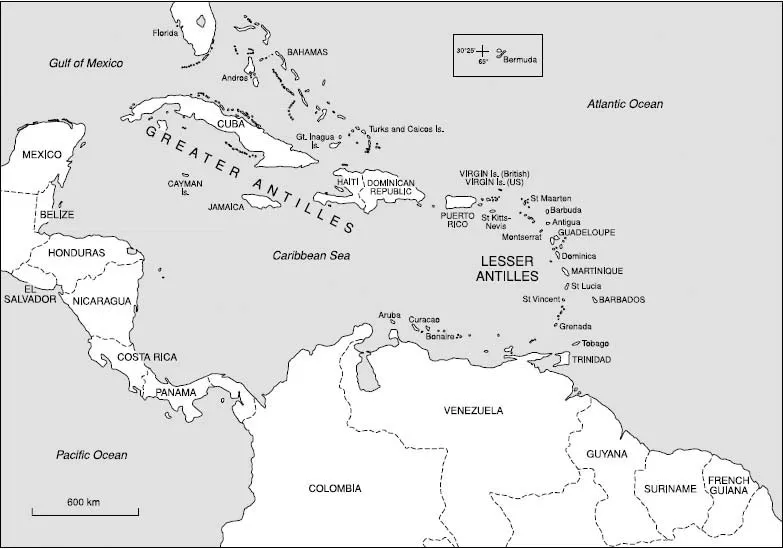

The Caribbean Basin and plate tectonics

The islands of the Caribbean Basin comprise three main geographic groupings; the Greater Antilles, the Lesser Antilles, and the islands of the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos archipelagos (Figure 1.2). A line of islands also fringes the north coast of South America, and the Cayman Islands lie to the west of the Greater Antilles. The Caribbean islands and their landforms have evolved as a result of the simultaneous interaction of endogenic (internal) processes from within the earth’s interior and exogenic (external) forces at work on the earth’s surface. Endogenic processes such as volcanic activity and earthquakes produce new landforms through uplift and island-building, whereas exogenic forces such as weathering and erosion remove surface materials and transport them elsewhere. In this section we explain how endogenic forces have shaped the geographical configuration of islands shown in Figure 1.2, and produced some of their distinctive landforms.

The Caribbean Basin was formed over an immense period of geological time as a result of tectonic forces from deep inside the earth’s interior which shifted, warped, folded and buckled sections of the earth’s surface. The theory of plate tectonics provides a basic framework for understanding these processes of deformation and recycling of rocks and the tectonic reconstruction of landforms. The theory was formulated in the 1960s and incorporates earlier theories of continental drift proposed in 1912 by Alfred Wegener, and sea-floor spreading proposed in the 1950s following deep-ocean drilling. The plate tectonics of the Caribbean Basin are a small but complex part of the planetary system of plate movements, and geologists have made great strides in unlocking the regional puzzle in recent years (Draper et al. 1994).

The earth’s lithosphere is segmented into rigid plates composed of either ocean crust or continental crust. Ocean crust is denser and heavier, but is only about 5–10 km in thickness (average = 7 km) compared with the continental crust, which may be as thick as 20–75 km (average = 33 km). Plates are of unequal size and are in constant relative motion. They move at infinitesimally slow rates of only a few centimetres per year (about the speed at which human fingernails grow). However, over the huge span of geological time, these minuscule annual plate movements are translated into distances of thousands of miles. Plates travel in different directions and at slightly different speeds, and over the millennia they collide and fuse together, or break up and fragment, altering the shape and geometry of the continents.

Figure 1.2 The islands of the Caribbean Basin

Source: Cartographic service, Geography Department, Indiana University

A significant aspect of the theory deals with the points of contact between plates because these narrow boundary zones correlate closely with global patterns of volcanic and earthquake activity and so constitute natural hazards for human populations. There are four types of plate boundary zone:

• Constructive boundaries – zones where plates move apart and new material emerges from the earth’s mantle. The African Rift Valley is a site of aborted spreading on land, and the mid-Atlantic ocean ridge is an example of the process occurring at the bottom of the ocean. The process is also termed ‘plate divergence’.

• Destructive boundaries – zones where plates collide, a process called ‘plate convergence’. When continental plates collide, fold mountains (e.g. the Himalayas) are thrust upwards. When two ocean plates collide, one is pushed beneath the other in a process known as ‘subduction’. As a plate is subducted, it sinks back into the asthenosphere under great pressures and temperatures, which cause it to melt as it descends. Melting releases basaltic and andesitic magma, which rises through the overriding plate to the earth’s surface, creating a linear pattern of volcanoes called a volcanic island arc. Destructive boundaries are associated with ocean trenches, the deepest parts of oceans.

• Transform boundaries – zones where plates slide past each other in opposite directions in a process called ‘transform movement’. These are also called ‘conservative margins’. Crust is neither being produced nor destroyed at these boundaries, which are most common in ocean settings. An example of a transform boundary on land is the San Andreas fault.

• Plate boundary zones – broad belts where boundaries are poorly defined and the effects of plate interactions are unclear.

Figure 1.3 shows the Caribbean is moving eastwards, at a rate of about 1–2 cm per year (Mann et al. 1990), relative to the North and South American ocean plates, which are moving westwards. The northern and southern boundaries of the Caribbean plate are associated with transform boundary movements, and are zones of earthquake activity. Their boundaries are difficult to pinpoint (Draper et al. 1994) so they are best characterised as plate boundary zones. On the western boundary, the Cocos and Pacific plates are moving eastward and are being subducted under the western margins of the Caribbean plate. This has created a chain of active volcanoes in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Guatemala. On the eastern boundary, the westward-moving Atlantic Ocean crust is being subducted under the Caribbean plate, forming the Puerto Rican ocean trench, which, at its maximum depth (9,220 m), is further below sea level than the summit of Mt Everest is above. The violent tectonic forces associated with A...