![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The sight and sound of Russian film

When are we to have music, the Text?

(Barthes, 1977, p. 77)

Cinema has become the dominant art form of the twentieth century and beyond, in Russia as almost everywhere else in the world. Cinema exerts its powerful influence through the twin powers of sight and sound, providing pleasure and stimulation through these most direct of senses. However, Russian cinema has not evolved in a vacuum and the major motifs and values of the ‘classical age’ of the nineteenth century have very much informed the images and themes developed by Soviet film-makers and which persist to this day.

Russian and European cinema

What is a national cinema? What makes Russian cinema ‘national’? What is distinct about Russian cinema and what cultural specifics inform its development? The task of this book is to address these questions and to affirm the aesthetic identity of Russian cinema within the totality of Russian and Soviet cultural discourse. Certain Russian aesthetic values, especially developed in its artistic and literary culture, have been passed down to cinema and have influenced the content and style of a film, so that in dialogical terms film culture has influenced or changed the appreciation of what can be widely termed Russian ‘art’.

In the chaos and disruption of post-Soviet Russia, the cinema industry has barely managed to exist, deprived of the state funding it once enjoyed and forced to look to private, occasionally shady, sponsors for resources. As a result, the number of films produced has sharply decreased. Yet those that are made – and some to great international acclaim – reflect a vision of Russia and explore the national experience and collective identity in a manner and style very different even from the cinema of Gorbachev’s glasnost a decade earlier. We are used to defining a ‘European’ cinema as one offering a cultural bulwark against the ever-increasing power of Hollywood, but is Russian cinema, for decades cut off from mainstream discourses, part of the European tradition? Recent attempts to define European cinema have concentrated on Europeans’ sense of their own cultural identity and feeling of nationhood:

The national question is, of course, more acutely felt by some film-makers than by others, but it is nevertheless a constant of European cinema and it finds a range of expressions. One is the reworking or re-appropriation of genres felt to be typically American, as seen in the Italian spaghetti western, the French crime film or polar, or the German road movie. Another is the attempt to repossess the national history, a particularly acute problem in relation to Germany or Russia.

(Forbes and Street, 2000, pp. 40–1)

Russian cinema can certainly be seen to be part of the European cinematic context in this respect. At the same time it has its own individual identity and ethos, factors driven and informed both by the experience of the last 100 years, but also by perceived ‘Russian’ cultural values passed down primarily by its literature.

What is striking to the foreign observer of Russian cinema is just how much of it is influenced not so much by currents and ideas from other cinema cultures – given the enforced isolation of most of the Soviet period this lack of penetration is understandable – but rather how many themes are as relevant today as they were over 100 years ago. Russian directors today, just as in the 1920s, see their brief as primarily to educate, not to entertain, and in their aspiration to address the burning issues of the day they resemble their nineteenth-century literary brethren. Many directors and producers in prerevolutionary cinema saw themselves not only as providing entertainment – they also sought respectability by adapting the literary classics and making films on historical themes.1 Many of the directors of the ‘golden age’ (approximately 1924–30) very deliberately set film up as the ‘high’ art of the Revolution, a highly intellectual medium through which political ideals could be expressed with maximum (i.e. visual) effect. But the Russian artistic heritage passed on not only its own self-importance, but also ideas of historical destiny, the fate of the individual and its great moral questions. Also, it encouraged a feeling for Russia as a country, an almost palpable sense of what Russia looks, feels and smells like, not simply a backdrop for various dramas. Here the role of the landscape, the natural contours of Russia, is highly relevant.

Landscape: art and literature

In his ground-breaking work on art, the natural world and cultural memory, the historian and broadcaster Simon Schama traces the profound fascination held through the centuries by scholars, artists and statesmen for nature’s basic components, in particular wood, water and rock. Moreover, this fascination has often been translated into aesthetic ideals or even political manifestos:

[…] It is clear that inherited landscape myths and memories share two characteristics: their surprising endurance through the centuries and the power to shape institutions that we still live with. National identity, to take just the most obvious example, would lose much of its ferocious enchantment without the mystique of a particular landscape tradition: its topography mapped, elaborated, and enriched as a homeland. [… ] The famous eulogy of the ‘sceptred isle’, which Shakespeare puts in the mouth of the dying John of Gaunt, invokes cliff-girt insularity as patriotic identity, whereas the heroic destiny of the New World is identified as continental expansiveness in the landscape lyrics of ‘America the Beautiful’.

(Schama, 1995, p. 15)

Landscape art is not only visually striking, but also appeals to deeper, emotional notions of home and being. Landscape art constructs certain inescapable cultural concepts:

Landscape in art tells us, or asks us to think about, where we belong. Important issues of identity and orientation are inseparable from the reading of meanings and the eliciting of pleasure from landscape. The connection between such fundamental issues and our perception of the natural world is a key reason for the proliferation of images of landscape over the last 500 years in the West, and particularly over the last 250 years.

(Andrews, 1999, p. 8)

Landscape in any national cinematic culture is therefore of enormous value, the first point of contact between viewer and director. We know that some of the early pioneers of Soviet film took a great interest in art. Lev Kuleshov’s father had dabbled in art and he himself says of his own teenage years:

More than anything else the rich, luxuriant, festive and often monumental art of the stage painters Korovin and Golovin imprinted itself on my soul And I decided to become a theatrical painter. [ …] Art – the theatre and painting – thrilled me comprehensively and imperiously.

(Kuleshov and Khokhlova, 1975, pp. 16–17)

Kuleshov studied painting privately and his tastes were eclectic, including Gauguin, Van Gogh, Picasso, Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Cézanne, Serov, Vrebel, Korovin and Surikov (Kuleshov and Khokhlova, 1975, p. 20). In other words, Kuleshov entered cinema not through any background in the theatre, as was more common, but through his exposure to art. Alexander Dovzhenko was another who worked in art before entering the cinema. His classic film Earth (1930) teems with images of mystical natural beauty and man’s place within it and in his writings he picked out the landscapes of Isaak Levitan as being ‘artistic, but with their sublime qualities distinct from the ten thousand mediocre things which seemed on the surface similar’ (Dovzhenko, 1967, p. 234).2

Furthermore, Russian art has a famous landscape tradition, especially in the nineteenth century, but one that transferred into images of natural beauty concepts of home, identity and patriotism. Soviet critics emphasised the critical realist painting of the Itinerants (‘Peredvizhniki’) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with their emphasis on real people and events and perceived social injustice. The paintings of Repin, Iaroshenko, Makovskii, Maksimov and others produce harsh and vivid images of suffering and dejection and were hailed as being ‘progressive’ and ‘democratic’. However, landscape painting can be seen as a corrective, a move from the harsh social realities towards a more aesthetic, even poetic mainstream. The work and ideas of nineteenth-century landscape artists, such as Levitan, Kuindzhi, Klodt, Shishkin and Kiselev are among the best in the landscape tradition; they convey peace, the harmony of nature and man and the epic greatness of the Russian land, a land where sky and earth meet and both stretch into the distance and eternity. Nature is seemingly alive, trees and grass rustling in the breeze, rivers as the great arteries of Russia.

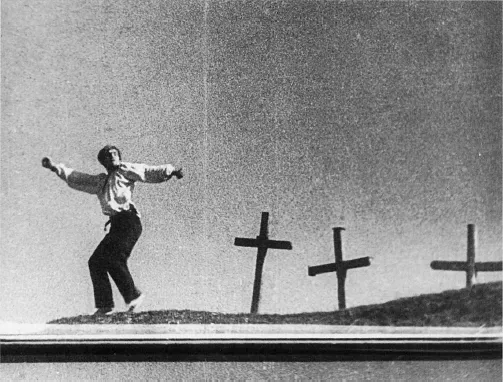

Petr Masokha in Earth (Alexander Dovzhenko, 1930)

The great writers of the nineteenth century, such as Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoi, Fet, Tiutchev and Turgenev, also expressed their fascination with Russia’s natural landscape, as well as that of the outlying reaches of the then Russian empire. Lyrical poems could find contentment in the deep forests or dewy meadows of Mother Russia. Other more adventurous souls would find excitement and awe in the majesty of the Caucasian mountains, the place where European Russia ends and the great unknown of Asia begins. As the century ends, nature comes under threat as Chekhov’s cherry orchard is cut down and the urge to modernise takes over.

Landscape and film

There is ample cinematic evidence, from the 1920s to the post-Soviet period, to affirm that Russian and Soviet directors imbued natural images with the symbolic significance explored by their cultural ancestors.3 Dovzhenko’s sky canvases of the 1920s speak of majesty and grandeur and of the essential unity of nature and man. A decade or two later, the bright, summer vistas of rural Russia, with sun-baked fields and gently winding rivers viewed from above, paraded before us in ‘optimistic’ comedies, speak of the greatness of Russia and its true blossoming under the benevolent eye of Iosif Stalin. Alexandrov’s Volga-Volga (1938) can be seen as a cinematic extension of Levitan’s Volga, for here, in Stalin’s Russia, the Volga leads inexorably to the centre of power, Moscow, where true achievement can be attained and recognised.

A more revisionist slant on the river-as-history theme could be possible only after the death of Stalin. Mikhail Kalatozov’s Loyal Friends (1954) sees three old friends rediscover their childhood values and friendship via a raft trip down the Iauza river. In the 1970s and early 1980s rural Russia became idealised as the repository of values seen as being lost in the drive toward modernity. Books as well as films were directed at what Kathleen Parthé calls ‘time backward’: the reverse flow whereby the passing of time and the ebbing away of old values signify the death of a way of life deeply connected with the natural world (Parthé, 1992, pp. 48–63).

What is interesting about the role of cultural memory in the development of Russian art, and in particular film, is that the move away from nature – urbanisation, collectivisation – has been viewed negatively, as the loss of true Russia, its age-old value systems and its very identity. Constructivism was hailed as the perfect blending of man and technology, the control and utilisation of space, for the machine age that beckoned in the 1920s, but ‘time, forward!’ became the somewhat forlorn and discredited slogan from the 1960s onwards. Progress, in the form of electricity, unites the country, closes down the otherwise indomitable expanse of Russia, but it is resisted by the antirational, anti-modern forces in Russia in the latter half of the twentieth century.

The natural expanse, contours and topography of Russia thus offer a cultural space for the articulation of myths and ideologies. Lands...