![]()

Chapter 1

Why Text-Based Questions?

Even though I made “As” most of the way through grade school, I do not believe I was adequately prepared for the rigors of higher education. While I thoroughly enjoyed my K–12 experience and believe I learned a lot, much of the work I did, even in my advanced classes, was not particularly challenging. Rather than teach me to think analytically, it simply required me to regurgitate facts—facts I had acquired from reading my textbook or actively listening to my teachers’ presentations. For this reason, I graduated high school with a false sense of confidence that I was ready for the challenge of a university education.

Reality hit home, however, by the end of my first day of college. In fact, I called my parents after classes to tell them that I was considering dropping out of school. The workload, I said, was too intense, and the reading was too complex. I had more reading to do in one night than I had ever done in a week during high school. Furthermore, I had a three-to-five-page paper to write by the end of the weekend (longer than any essay I had to write in high school), and a test to start studying for that would constitute 25 percent of my entire semester grade. Fortunately, my parents managed to calm me down and convince me to stay in school; after a few months of very hard work, I began to feel more confident about my ability to do well. Still, I believe there was too great a gap between the expectations of my high school teachers and the demands placed on me by my university professors.

Perhaps if I had taken more AP classes in high school, I would not feel this way. My AP English class, which I took as a junior, was the one most closely aligned with college-level expectations. Our reading assignments were diverse, and our essay prompts required at least a shred of analytical thinking. Books we read included The Scarlet Letter (Hawthorne, 1850), A Separate Peace (Knowles, 1959), As I Lay Dying (Faulkner, 1930), and The Great Gatsby (Fitzgerald, 1925). While we read other classic works of literature in my other English classes, such as Silas Marner (Eliot, 1861), The Canterbury Tales (Chaucer, 1400), and Romeo and Juliet (Shakespeare, 1597), I do not remember reading anything but the textbook in any of my other subjects.

Looking back, I should have taken more AP classes when I was in high school. Even though some of the courses offered now, such as AP human geography and AP world history, did not exist then, there were plenty of other AP classes for me to choose from. However, at that time, I naturally assumed that a high school education consisting mostly of honors classes would mirror the expectations of university professors and more than adequately prepare me for college.

I suspect a lot of students today assume this as well. I know my own students, including students in my non-advanced courses, talk about college as if it will simply be an extension of their high school education. They talk about going to the University of Florida and other universities in our state as if their academic experiences at these schools will closely resemble their high school experiences. In fact, students sometimes complain about the work they are expected to do in my classes, asking if they will ever have to do this much (and this kind of) intellectual work in college.

I cannot help but chuckle, at least on the inside, whenever my students ask me this question, especially when they insinuate that kids these days are being made to work so much harder and “be so much smarter” than students were when I went to high school almost 15 years ago. Because I do not want to make them feel bad, I do not tell them that there is a lot of evidence to suggest that students today are not working harder, and are not any smarter, than they were 15 or 30 years ago. If anything, they are falling behind their peers in other parts of the world. For example, the United States currently ranks 25th in math and 21st in science among 30 developed countries. When the comparison is restricted to the top 5 percent of students, the United States ranks last. In 1970, the United States produced 30 percent of the world’s college graduates. Today, however, it produces only 15 percent. Since 1971, education spending in the United States has more than doubled from $4,300 per student to more than $9,000 per student. Yet reading and math scores have remained flat in the United States, even as they have risen in virtually every other developed country (Weber, 2010).

There are several reasons for this disparity in student achievement. First, students do not possess the skills they need to compete globally in the 21st century. In his book The Global Achievement Gap (2008), Tony Wagner identified seven important skills our schools are not currently teaching. These skills, which include critical thinking and problem solving, effective oral and written communication skills, and accessing and analyzing information, are a must-have for the future. Yet, sadly, only 1 in 20 classes in our nation’s best schools are teaching them. Second, schools are narrowing their curriculum in order to show progress on state tests that emphasize math and reading. Instructional resources are being diverted toward these subjects and away from subjects such as art, music, foreign language, and social studies (Farkas Duffet Research Group, 2012). Third, students are becoming increasingly lazy. According to Thomas Friedman (2005), American students do not work as hard as students in other countries. This is especially true when American students are compared to students in countries like Finland, Singapore, Korea, and China (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

Additionally, each state in our country has developed its own standards for measuring student achievement. What a student is expected to know in Idaho, for example, is not necessarily what a student is expected to know in Florida. Furthermore, the standards developed by individual states during the past two decades are primarily content driven and are generally not as rigorous as standards in other developed countries. On the other hand, the Common Core State Standards are internationally benchmarked to ensure that students are college- and career-ready and can compete with their peers around the globe. Instead of being content driven, the Standards emphasize the development of skills students need to be truly literate in the 21st century—the same skills Wagner said our schools should be teaching. While content will always be important, we, as teachers, must stop making content coverage our primary focus and focus instead on teaching these skills.

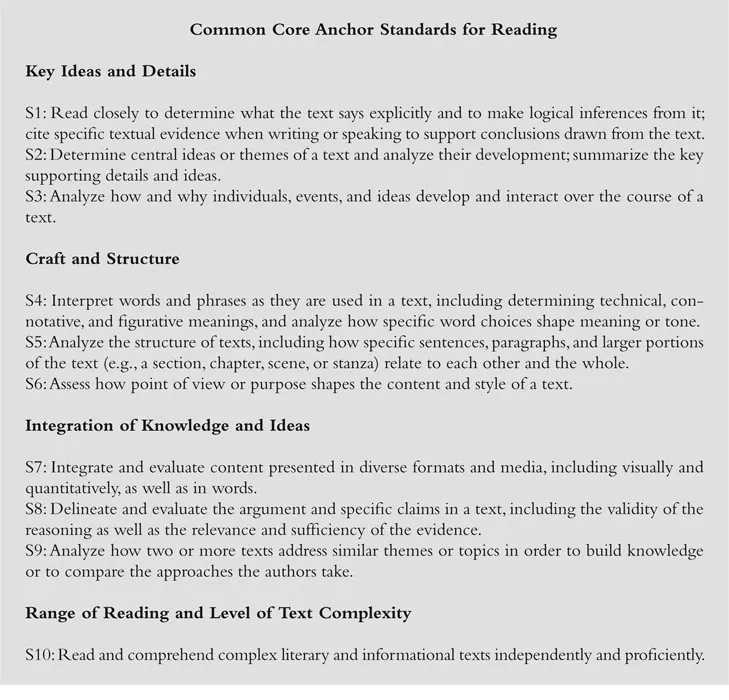

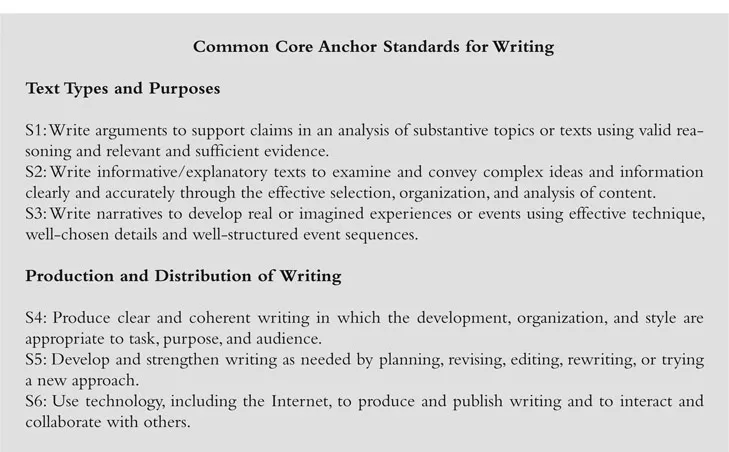

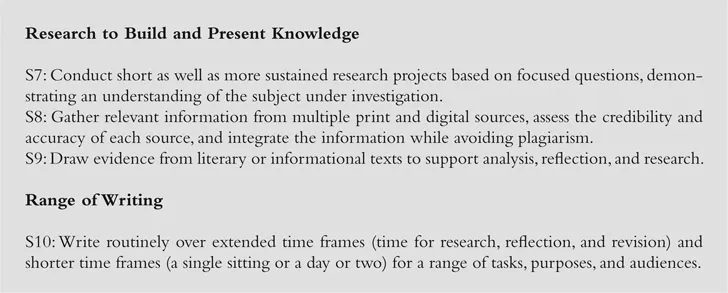

In the past, the responsibility for teaching literacy skills fell almost exclusively on English teachers. Today, the expanding concept of literacy requires that teachers in all grades and content areas share this responsibility. Teaching these skills will certainly be a challenge, considering many K–12 students have been raised on a system that has not emphasized critical thinking. Therefore, if we expect all students to master the Common Core grade level and anchor standards before graduation (see Figure 1.1), we must develop and use effective tools for teaching content as well as analytical thinking and writing.

Text-based questions are such a tool. Broadly defined, TBQs are questions that can only be answered by referring back to the text. While not all TBQs require high-order thinking, good TBQs require students to analyze and evaluate what they are reading and support their responses with strong textual evidence. Unlike questions that require students to recall factual information, good TBQs integrate skills with content and facilitate a deeper reading of texts. More complex TBQs require students to work with multiple sources written from different points of view and understand how those sources work together to answer a question. While background knowledge may be useful to

Figure 1.1 Common Core Anchor Standards for Reading and Writing

Source: CCSSI, 2010

students for answering the question, their answers must always be supported with evidence from the text.

Even though school districts around the country are just now beginning to encourage the use of TBQs in all K–12 classes to teach analytical thinking and writing skills and meet the nonfiction requirements of Common Core, TBQs have been around for quite some time. Since 1973, the College Board has been using a form of TBQs, called document-based questions (DBQs), on its AP history examinations to assess students’ ability to work with historical documents (including primary sources). The creators of the DBQ, Giles Hayes and Stephen Kline, were unhappy with students’ answers to free-response questions. Like the thematic essays typically assigned to high school students in non-AP courses, these questions allowed students to parrot back information with little historical analysis or argument. The purpose of creating the DBQ was to make students less concerned with factual recall and more concerned with getting students to think and write like historians (Henry, n.d.).

Today, TBQs make up part of the AP U.S. history, AP world history, AP European history, and AP English language and composition exams as well as the history exams given by the International Baccalaureate (IB) and Advanced International Certification of Education (AICE) programs. They are also a part of the New York Regents Examinations in U.S. history and government and global history. However, TBQs are not just for high school students, students in advanced classes, or those taking history courses. They are useful to students in all grades and subjects. In fact, what makes TBQs such an effective and versatile tool is their ability to be used by teachers in all grades and content areas to teach students how to analyze, evaluate, and write about informational, literary nonfiction, and visual texts. They can be written for any subject, be about any topic, and incorporate as many different types of sources (written from as many different points of view) as teachers choose. They can be easily incorporated into regular classroom instruction and can be completed individually, in small groups, or as a class.

My own journey with TBQs began during my first year of teaching. After completing my internship and graduating from college in the spring of 2003, I was hired to teach AP world history and world history honors at a brand new high school in northeast Florida. Because my experience teaching AP courses was obviously very limited (I taught AP human geography during internship but under the supervision of a directing teacher), my principal sent me to a week-long training that summer in Atlanta, Georgia.

Despite having read the 100-page course description for AP world history before leaving for Atlanta, I arrived at the training with very little knowledge about TBQs. Fortunately, most of the other teachers at the training knew little about TBQs as well, so our instructor spent a lot of time on them. A few hours each day were spent looking at TBQs, discussing them as a group, and grading sample student responses. By the time the training was over, I felt I had a better understanding of what I was supposed to cover in the course as well as how TBQs were supposed to be read and scored.

What I did not have, however, were resources I could use for teaching TBQs. While I obviously had copies of the TBQs we used during the training, these were not enough. In order for my students to get sufficient practice working with TBQs, I was going to need at least a dozen more. Furthermore, I was going to need something easier than any of the TBQs we were given at the training. These TBQs were truly AP caliber—that is, they were as challenging as the TBQs students would see on the AP exam in May. Given that this was August, I was going to need something simple to start with. Over time, of course, the TBQs could become increasingly challenging.

I looked online for what I needed; but, unfortunately, there was nothing— nothing, at least, that I could use at the end of August as opposed to May. That being the case, I set to work creating my own TBQs. Starting with the Neolithic Revolution and ending with the collapse of the Soviet Union, I created more than 20 TBQs for use in AP world history—TBQs that got progressively more challenging as the year went on.

At the same time, I began developing effective strategies for teaching my students the skills they needed to complete TBQs successfully. For example, I developed specific techniques for getting my students to ask questions of their reading (the first step toward analysis) and for distinguishing one type of text from another. I developed strategies for teaching point of view and understanding the relationship between sources. I taught them to formulate a thesis statement, write analytical essays, and cite textual evidence. I got them thinking about what points of view were missing from the texts and to suggest additional texts they thought would be helpful. While these strategies were—and still are—a work in progress, they served their purpose. By the end of the year, my students’ skill set had improved dramatically. Not only could they navigate different types of text and write analytical essays, their vocabularies, I noticed, had significantly improved, and they made fewer spelling and grammatical errors.

When my students’ AP scores came back in July, the results supported the growth I had witnessed during the year. Eighty-three percent of my students passed the exam with a 3, 4, or 5—the highest percentage in the entire school. The next year, the results were even better: 92 percent of students passed the exam. In 2005, I took on an AP European history class in addition to AP world history and had 100 percent of my students pass that exam.

Obviously, I was very proud of my students’ success. However, I w...