eBook - ePub

Prehistory of North America

Mark Sutton

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 432 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Prehistory of North America

Mark Sutton

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A Prehistory of North America covers the ever-evolving understanding of the prehistory of North America, from its initial colonization, through the development of complex societies, and up to contact with Europeans.

This book is the most up-to-date treatment of the prehistory of North America. In addition, it is organized by culture area in order to serve as a companion volume to "An Introduction to Native North America." It also includes an extensive bibliography to facilitate research by both students and professionals.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Prehistory of North America un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Prehistory of North America de Mark Sutton en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sozialwissenschaften y Archäologie. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

| CHAPTER | |

Introduction

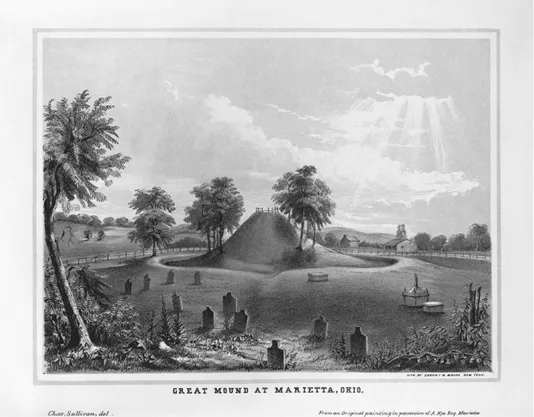

As Europeans settlers began to enter the regions west of the Appalachian Mountains, they encountered large, sophisticated, and complex earthworks (Fig. 1.1) in the form of pyramids, conical mounds, and linear mounds, some in geometric forms and others as representations of animals. Some of these mound complexes looked to Europeans like defensive constructs and were called “forts.” Early investigations of the mounds revealed some details of their complicated construction, and many contained elaborate burials and exotic materials. It was realized that the construction of the mounds would have required a huge investment in labor, but it was thought that were too few Indians currently living in those regions to have built them. So, who had built these mounds? How could this have been done? What happened to the people who built them? The mystery of the “Moundbuilders” generated considerable public interest and was the subject of a great deal of speculation (see Silverberg 1968; Tooker 1978; Willey and Sabloff 1993:22–28, 39–45).

To some of the people first looking at this question, it seemed impossible that the Indians were responsible, partly due to the racist view that the Indians were not intellectually or culturally capable. Speculation then centered on some sort of a “lost race” of white people—perhaps an old and vanished group of Europeans or one of the Lost Tribes of Israel. Others thought that the mounds had indeed been built by Indians. For many decades, considerable ink was spilled in speculation concerning this issue, but very little actual work was done to uncover the truth behind it. The problem was more than just academic. If whites could be shown to have previously occupied the interior of eastern North America, a much better case could be made for taking the land “back” from the Indians.

By the early 1800s, some actual fieldwork to document and describe some of the many mound sites was beginning to be undertaken. The most important of these was the now classic study of Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin U. Davis (1848), who documented a large number of mound sites in the Mississippi Valley. In the end, they concluded that the mounds had been built by some “lost race” of whites. The “lost race” theory was subsequently rejected by Haven (1856), who wrote the first general summary of the archaeology of the United States. The debate subsequently continued to rage.

FIGURE 1.1 The Marietta Mound in Ohio as it appeared in 1840 (from Squire and Davis 1848: 40).

(Source: © CORBIS All Rights Reserved.)

By the late 1800s, the discipline of archaeology was beginning to become professional, and some serious archaeological investigations were undertaken, often by the newly formed federal Bureau of Ethnology. The moundbuilder issue was important and popular enough that Congress itself assigned the Bureau to investigate and resolve the problem. Cyrus Thomas was given the task and undertook to develop the necessary evidence in a scientific and objective fashion. Thomas assembled the existing data, undertook new surveys and excavations of some mounds, and concluded that the Indians had built the mounds (Thomas 1894). The “lost race” hypothesis was rapidly discarded, and attitudes about the Indians slowly began to change. Today we know that the mounds were constructed by a number of different Indian groups at various times in the past, some as recently as the early 1700s. One of the moundbuilder sites, Cahokia, is located near the city of St. Louis, covers more than five square miles, and contains more than one hundred mounds, including Monk’s Mound, the largest single mound in North America. A video on the Moundbuilders is available at www. archaeologychannel. org, “Legacy of the Mound Builders.”

The debate over who built the mounds is instructive. After more than one hundred years of speculation on this relatively simple problem, which had racial and political overtones, a concerted effort by scientific archaeology solved it rather quickly. As a result, attitudes toward the Indians began to improve and an appreciation of the fantastically complex prehistory of North America began to emerge, along with the realization that a great deal of archaeological work would be required to discover and understand that prehistory.

Today, a great deal of archaeology has been done, and our knowledge of North America’s past is vastly greater than it was a hundred years ago. New techniques and approaches have made it possible to investigate things that were undreamed of just a few years ago. Who would have known in the 1930s that we would be able to use radiocarbon to accurately date just about any organic material? Who would have guessed in 1990 that we would be able to determine the genetics of early Americans through DNA analysis? What will we be able to discover ten years from now? As we learn more about the past, old interpretations are discarded and new ones are adopted. New and more interesting questions can be addressed, and the search for the past becomes more and more exciting.

Understanding North America’s past is of great archaeological importance. It was one of the last places to be colonized by people and provides a natural laboratory for investigating many anthropological questions. Humans entered North America with one or two basic adaptations—terrestrial hunter-gatherers and/or maritime hunter-gatherers—a relatively short time ago (compared to Old World prehistory), although exactly when people first arrived is still uncertain. Once in North America, people developed a complex array of social and political entities, from hunting and gathering bands to (perhaps) agricultural states. How did this happen? How did such a large and linguistically diverse group of cultures develop in California? What was the role of women in early North American societies? What happened to the ancestral pueblo people in the Southwest? What was the role of warfare in the development of political complexity in the Northwest Coast? Was Cahokia really the center of a state-level society? The number of such questions is seemingly endless, and as we expand our knowledge of the archaeology of North America, we can begin to address them. There is so much more to learn.

THE STUDY OF THE PAST

The study of North America’s past is conducted primarily through archaeology, the recovery and analysis of the material remains left by past peoples. Archaeology employs a series of techniques to discover, recover, and interpret the past through the study and analysis of the materials found in archaeological sites. In North America, the archaeology of native groups before written records (e. g., prior to contact by Europeans) is generally called prehistoric, the archaeology of native groups just after contact with Europeans is called ethnohistoric, and the archaeology of groups after the time of written records is generally called Historic Archaeology.

Other sources of information employed by archaeologists include the historical record, such as the accounts of explorers, missionaries, and the military. Even in historic times, however, many events were unrecorded, and these events can be elucidated by archaeology. Detailed written descriptions of native peoples, or ethnographies, can provide a great deal of information useful to archaeologists. Finally, additional information about the past can be obtained in the oral traditions of native groups (Vansina 1985; Echo-Hawk 2000).

An interpretation, or series of interpretations, of the prehistoric past based on information generated by archaeology is called a prehistory. Thus, a prehistory is really an account of what happened in the past based on current information. As more information is obtained through archaeological research, the understanding of prehistory is constantly revised. This is an never-ending process of data acquisition and reinterpretation and is the way all Western science operates.

To begin to construct a prehistory, one begins with some basic understanding of remains through space and time. Once a basic idea of the archaeology of a region has been obtained, the information can be synthesized into definitions and descriptions, known as culture history, of the past groups for that region. In conjunction, the delineation of cultural chronology, the description and sequences of groups through space and time, is also a major goal. The basic culture histories of most regions of North America are now known.

Archaeological information is generated first through the discovery and description of archaeological materials in archaeological sites—artifacts, ecofacts, and features. A site is a distinct geographic locality containing some observable evidence of past human activity, such as broken tools (artifacts) or abandoned houses (features). Material remains, including the artifacts, ecofacts, and features within a site, are distributed in patterns that reflect past behaviors, somewhat like evidence at a crime scene. Some sites may be small and fairly simple, while others may be quite large and extend over broad areas. Large sites often contain distinct areas, or loci (singular: locus), within them, such as areas where tools were made or plants were processed. Sites can be classified into many types based on a number of criteria. Three of these are (1) geographic context, such as open sites, rockshelters, and caves, (2) function, such as habitation, storage, and ceremonial, and (3) age, such as Pleistocene or historic.

In many cases, materials will begin to accumulate on a site and a site deposit will develop. Soils that form as the result of human activity are generally called midden soils and often contain broken tools, used-up artifacts, plant and animal remains, charcoal and ash from fires, and general household trash, all mixed together and decomposed. Sometimes a midden may contain stratigraphy, which is layers of different materials deposited on top of each other.

All archaeological materials in a site belonging to a particular group or time period constitute a site component. All sites contain at least one component, and some contain many. Thus, a site may be said to have “a Clovis component” or a “Middle Woodland component,” meaning that part of the site deposit dates from those time periods.

Artifacts are the basic units of archaeological analysis and consist of portable objects made, modified, or used by humans. Examples of artifacts include projectile points (arrowheads), ceramic vessels, grinding stones, baskets, and hammerstones. In addition, the debris left over from the manufacture of tools or other objects is also considered artifacts. Natural materials altered by humans, such as the burned rocks around a hearth, are commonly found in a site but are not considered artifacts.

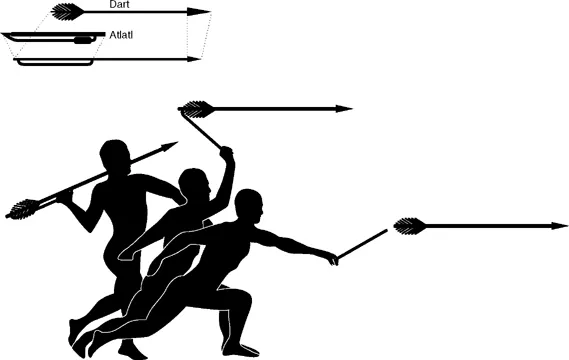

Native North American peoples utilized a variety of weapons prior to the introduction of firearms and metal knives and blades by Europeans. Among the most common were the spear, harpoon, atlatl and dart (see Fig. 1.2), bow and arrow, and blowgun. These weapons utilized sharp tips, sometimes of wood or bone but often of stone. These “projectile points” (e. g., spear points or arrowheads) are very important artifacts to archaeologists since many are of specific styles that can be placed generally in time.

Ecofacts are the unmodified remains of biological materials used by people, such as the bones of animals killed for food or the remains of plants, such as seeds, charcoal, and pollen. While an unmodified bone from an animal used as food is an ecofact, it would become an artifact if it were made into a tool.

Features are nonportable constructions people manufacture for some purpose. Features occur in a wide variety of forms and sizes, including fire pits (hearths), trails, canals, rock art, and earthworks. Sites can contain many features of various kinds, including hearths, pits, floors, structures, and caches.

The remains of humans themselves are often found in sites and can take a variety of forms. Some human materials, such as baby teeth or even an occasional limb bone, represent body parts lost during life and do not necessarily indicate the presence of a burial. If the dead were interred in a site, the remains would generally occur as either inhumations (burials) or cremations, although naturally mummified remains are sometimes discovered.

FIGURE 1.2 The atlatl/dart system. The atlatl is a device used to propel a large “arrow-like” dart with greater force and accuracy than an arrow. Nevertheless, the bow and arrow replaced the atlatl/dart across North America.

Information on sites and their contents is generated through the process of survey and excavation. To find sites, one has to actually go out on the ground and look for them, a process called archaeological survey (or inventory). Some surveys cover large areas and can result in the discovery of large numbers of sites. Much of the archaeology done in the United States today is survey work conducted during environmental studies, a part of archaeology known as cultural resource management (CRM). When a site is discovered in a survey, it is recorded, mapped, described, and assigned a site designation (commonly the state, county, and a number, such as CA-KER-450—the 450th site formally recorded in Kern County, California) so that other researchers know of its existence and an evaluation of its significance can be made.

Some of the sites recorded are investigated further, generally through excavation. Some are selected for excavation due to their importance to a specific research goal or project. Others are excavated because they will be destroyed by some development project, such as a dam or housing tract. Today, an explicit research design—or project plan that outlines why a site is being excavated, the methods used, and the kinds of information sought—is required prior to most excavation work. Excavations can be very small to very extensive, depending on the site itself and the project requirement...