eBook - ePub

Intermediate Microeconomics

Neoclassical and Factually-oriented Models

Lester O. Bumas

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 544 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Intermediate Microeconomics

Neoclassical and Factually-oriented Models

Lester O. Bumas

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This is the first intermediate microeconomics textbook to offer both a theoretical and real-world grounding in the subject. Relying on simple algebraic equations, and developed over years of classroom testing, it covers factually oriented models in addition to the neoclassical paradigm, and goes beyond theoretical analysis to consider practical realities.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Intermediate Microeconomics un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Intermediate Microeconomics de Lester O. Bumas en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Business y Business General. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

CHAPTER ONE

Some Economic Perspectives

Economics is a fascinating, dynamic discipline. This is essentially so because the economy continually changes, and economists are continually trying to understand why these changes have come about. But the ruling economic theory has not readily changed. The current paradigm is roughly a century old—and may be in need of some serious updating.

Adam Smith is generally credited as the founder of economic analysis. The paradigm of Smith and his followers is called “classical economics.” That system of ideas, ideology if you will, dominated economic thinking from 1776 to roughly a century later. Smith stressed the role of productivity growth in advancing a nation’s living standards. David Ricardo combined Smith’s analysis with Malthus’s theory of population to attain long-run predictions regarding the distribution of income among workers, capitalists, and landowners.

The production-supply-side approach of Smith and his followers was countered by the demand-side stress of William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, and Carl Menger. In the 1870s they independently discovered or rediscovered marginal utility-demand analysis. They emphasized it to such an extent that virtually no recognition was given to the supply side. Shortly thereafter Alfred Marshall developed a new paradigm which is still in vogue today, “neoclassical” economic analysis. It combined the supply- and the demand-side approaches. The main concern of the neoclassical paradigm became efficient resource allocation in a static economy, quite at odds with the classical school’s focus on the dynamics of growth and the distribution of income.

Adam Smith’s Emphasis on Increasing Productivity

The title of Adam Smith’s 1776 masterpiece, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, implies that Smith felt that the primary concerns of economics were the material well-being of people and the way in which it could be increased. Smith saw the “division of labor,” specialization in narrow areas of work, as the key to increasing productivity and production. The effects were direct and indirect. Narrow specialization could directly increase the expertise and productivity of workers and save time in moving from one part of the process of production to another. Then, with production broken down into numerous small tasks, machinery could be designed more readily to augment productivity further and more dramatically. Smith’s famous growth example is that of a pin factory in which labor productivity was greatly increased by the division of labor and mechanization:

These ten persons [with the division of labor and mechanization] … could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins a day. Each person might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently … they certainly could not have made twenty; perhaps not one pin in a day (1937 [1776], p. 5).

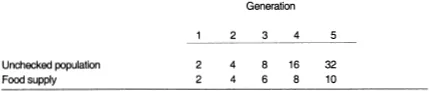

Table 1.1. | Malthus’s Theory in Numerical Form |

Productivity growth remains a major contemporary concern. Substantial productivity growth was experienced in our post-World War II economy. But starting about 1973, productivity growth declined and has yet to regain the rate experienced in the earlier period. The significance of the decline is indicated by the fact that had we maintained the growth rate of the 1948–1965 period, our 1990 national output would have been roughly 50 percent greater than that actually experienced.

Ricardo’s Stress on the Future Distribution of Income

The classical model, created by David Ricardo, combined a polished version of the analytical. content of Smith’s work and the population theory of Thomas Robert Malthus. The Reverend Malthus, by the way, wrote his famous essay on population as a polemic against the proposal of English Prime Minister William Pitt to liberalize the dole, the scant welfare payments doled out to the poor. The Malthusian theory of population is really a model of population and food supply growth. Unchecked, Malthus had the population growing as a geometric series: two begets four; four begets eight; eight begets sixteen; and so on. At best, Malthus guessed, the food supply could be increased as an arithmetic series, a series with equal increments, here over each generation. Appropriate numbers for the growth of population and food appear in Table 1.1.

The numbers imply that for the first and second generations, population and food supply growth are in accord. Starting with the third generation, however, there is an increasing shortfall of food per person. Growth in the population is then checked by malnutrition and starvation. Malthus contended that any rise in the standard of living above the subsistence level, coming from a good harvest or a more generous dole, would result in an increase in population growth until living standards were again driven down to or below the subsistence level. The only thing that would help the poor, according to Malthus, was their abstinence from procreation—not far from an important argument in the debate of recent years on welfare reform.

Ricardo’s dynamic model is primarily concerned with the prospective returns to the owners of labor, capital, and land. As Ricardo saw it, the standard of living of the masses would tend toward the subsistence level. Were the standard of living higher, population would increase driving living standards back to the subsistence level. As investment in plant and equipment increased over time, new investment opportunities would disappear and the rate of profit would tend to fall toward zero. Only landowners would prosper as a result of the fixed supply of land and an increasing demand for it by a growing population.

Ricardo’s analysis and forecasts were developed in the 1815–1819 period. Fortunately, the English economy paid no heed to them. Statistical evidence available in the 1830s and 1840s falsified every one of these Ricardian predictions according to Mark Blaug. Nonetheless, Ricardo’s classical paradigm dominated economics for another half-century.

Marginal Utility Analysis: Transformation of the Focus of Economics

During the 1870s William Stanley Jevons, Leon Walras, and Carl Menger independently discovered or rediscovered marginal utility analysis. Their work displaced the then existing focus of economic analysis in several fundamental ways:

• It replaced the classical focus on dynamic change with one concerned with the operation of the economy at a moment in time.• It changed the basic focus of economic analysis from productivity, the standard of living, and the distribution of income to the efficient use of resources for the benefit of consumers.• It replaced the stress of the classical model on the supply side, the side of production, with stress on the demand side, particularly consumer demand.• It broadened and stressed maximizing behavior. Consumers were theorized as maximizing their satisfaction, workers as determining the hours per week they would work to maximize their satisfaction, and producers theorized as maximizing profits.

This fundamental change is sometimes called the marginal revolution.

Jevons’s opinion concerning what economics should be about is summed up in the last chapter of his 1871 work, The Theory of Political Economy. In it he essentially defined the neoclassical perspective decades before its arrival:

The problem of economics may, as it seems to me, be stated thus: Given, a certain population, with various needs and powers of production in possession of certain lands and other sources of material: required, the mode of employing their labour which will maximize the utility of the produce (1970 [1871], p. 254).

Jevons’s slighting of the supply side went so far as to make the costs of production irrelevant with respect to price setting. What was relevant to him was the willingness of the holder of a good to sell from his inventory at a price acceptable to buyers. There is no explicit or conscious recognition of the firm, the institution of production, and its need for revenues to cover its costs.

Alfred Marshall and Neoclassical Economics

Alfred Marshall created what is now called “neoclassical economics” toward the end of the nineteenth century. The first edition of his Principles of Economics was published in 1890. His text is far richer in cultural and institutional matters than are modern economic tracts as indicated by his definition of economics:

Political Economy or Economics is the study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of wellbeing.Thus it is on the one side a study of wealth; and on the other and the more important side, a part of the study of man. For man’s character has been molded by his every-day work, and the material resources which he thereby procures, more than by any other influence unless it be that of his religious ideals (1961 [1890], p. 1).

Particularly interesting is Marshall’s contention that our character is strongly affected by economic and religious institutions, those stressed a half-century earlier by a famous follower of Ricardo, Karl Marx. “The more important side,” the study of man, has been obviated by the construction of “Economic Man,” a maximizing robot.

Popular Perspectives Defining Economic Activity

Two of the most popular approaches to defining the realm of economics are those associated with Frank Knight, a founder of the Chicago school of economics, and Lord Lionel Robbins. Knight’s approach can be viewed as institutional. It stresses the role of the social organizations required to respond to what are deemed the basic questions of economics. Robbins’s approach is highly abstract or analytical and yi...