![]()

1

THE STUDY OF TERRORISM AND COUNTERTERRORISM

Andrew Silke

Introduction

Terrorism and counterterrorism have always been challenging subjects to study. Emotive, controversial and sometimes even dangerous, throughout the 20th century the study of both has lurked on the fringes of scientific research. There were few scholars willing to commit their careers to the area, funding was extremely limited and inside and outside academia there were plenty who questioned whether terrorism and counterterrorism were even appropriate subjects for scientific study, and questioned too the motives of any researcher willing to explore such controversial issues.

It was only after the 9/11 attacks in 2001 that terrorism moved from the fringes of scientific interest to a subject of major attention. Controversy remained, but the funders of research were now taking it seriously as a subject of interest. Prior to 9/11, research on terrorism had usually been conducted on shoestring budgets. Ultimately, a lack of funding and a shortage of researchers stifled the ambition of research plans. Expensive and time-consuming methodologies and analysis could only rarely be contemplated. Instead, making do with what was available, researchers favoured methods and approaches which could be accomplished with the meagre resources at hand. The result was that, although quite a lot was still written, much of it was of limited quality, often adding little or no new data to the field. Adding to the mire, much of the research was often conducted by authors with only a limited understanding of the existing literature on terrorism, with a result that a lot of dead-end research was unnecessarily repeated and some of the rest was incredibly poorly linked with the rest of the field.

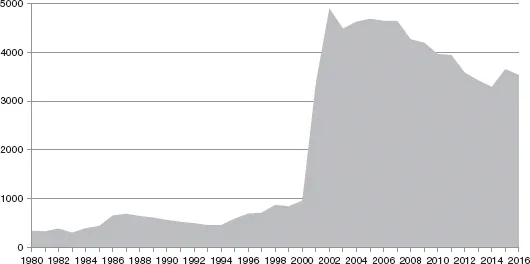

Much of this changed in the aftermath of 9/11. There was a massive surge in research interest on terrorism and counterterrorism and as Figure 1.1 highlights, a dramatic and instant change. The figure shows all the scholarly works recorded by Google Scholar which had at least one of the following terms in the title: terrorism, terrorist, political violence, radicalisation, radicalisation or insurgency. This, though, should not be seen as a complete tally of the relevant research. A book or an article which focused on a particular terrorist group or conflict but which did not use any of the search terms in its title would be missed. Nevertheless, the graph demonstrates that almost overnight, terrorism went from an exotic curiosity to a subject of apparently strategic international importance. Research budgets were massively increased and substantial funding was made available for a wide range of studies. Major new research centres and institutes were established at many universities, while the handful of existing centres were able to grow significantly in size and scope.

Figure 1.1 Scholarly publications on terrorism and counterterrorism, 1980–2016.

Terrorism and counterterrorism entered university course curriculums across the globe and became widely taught. Today it is rare to find any medium-sized university in the West which does not offer at least one module on terrorism in its syllabus. Before 9/11, it was a rarity.

Figure 1.1 also illustrates that the surge in interest has largely been sustained in the years following 2001. New research continues to be published at a formidable rate. Almost 35,000 scholarly works have been published since 9/11 with ‘terrorist’ or ‘terrorism’ in the title. That number jumps to 635,000 if you also include those works which mention terrorist or terrorism somewhere in the text. It averages at over 100 scholarly works published each and every day since 9/11: books, journal articles and theses. Keeping track of such a blizzard of research and analysis is a massive challenge in itself. And yet, despite this incredible flood of output, a recurring fear among researchers is that the study of terrorism and counterterrorism is actually failing.

Challenges in understanding terrorism and counterterrorism

A variety of factors drive this fear of failure, but the reason most often cited is that the research methods used to study terrorism and counterterrorism are too weak. A vocal recent critic is Marc Sageman (2014), who argued that research on terrorism has stagnated. In a stark overall analysis, he concluded that:

Overall, the post-9/11 money surge into terrorism studies and the rush of newcomers into the field had a deleterious effect on research. The field was dominated by laymen, who controlled funding, prioritizing it according to their own questions, and self-proclaimed media experts who conduct their own ‘research.’ These ‘experts’ still fill the airwaves and freely give their opinions to journalists, thereby framing terrorist events for the public. However, they are not truly scholars, are not versed in the scientific method, and often pursue a political agenda. … The voice of true scholars is drowned… it is hard to escape the judgment that academic terrorism research has stagnated for the past dozen years because of a lack of both primary sources and vigorous efforts to police the quality of research, thus preventing the establishment of standards of academic excellence and flooding the field with charlatans, spouting some of the vilest prejudices under the cloak of national security.

(Sageman, p. 8)

This was not the first time that experienced researchers had hit out at the poor quality of large amounts of terrorism research. In an early famous review of research, Schmid and Jongman (1988) found that most researchers were not producing substantively new data or knowledge. Instead, they were primarily reworking old material which already existed. In the 1980s, only 46 per cent of the researchers said that they had ever managed to generate data of their own on the subject of terrorism. For the majority of researchers, all of their writings and analyses were based entirely on data produced by others.

Figure 1.2 comes from a review at the end of the 1990s which showed that researchers remained very heavily dependent on easily accessible sources of data. Only about 20 per cent of articles provided substantially new knowledge which was previously unavailable to the field. The field thus was very top-heavy with what are referred to as pre-experimental research designs. Unfortunately, these are ‘the weakest designs since the sources of internal and external validity are not controlled for. The risk of error in drawing causal inferences from pre-experimental designs is extremely high and they are primarily useful as a basis... for exploratory research’ (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 1996, p. 147).

Figure 1.2 Methods in terrorism research (Silke, 2001).

There was some improvement after 9/11, but a 2009 review still found that only 35 per cent of articles in the core terrorism studies were providing new data (Silke, 2009). Most of the rest were again essentially rehashing knowledge that was already there. This leads us back to Sageman’s stagnation argument, which recognised that while a great deal was being written on terrorism and counterterrorism, the heavy reliance on weaker methodologies and limited data analysis meant that the field was failing to make meaningful progress.

There was a polemic edge to the stagnation argument and many serious and experienced terrorism researchers countered that Sageman had overstated the case (e.g. Taylor, 2014; McCauley and Moskalenko, 2014). Yes, there were a lot of mediocre studies, but there were also definite signs of progress. Indeed, some have argued instead that the study of terrorism and counterterrorism is actually in a golden age: a period of unparalleled research activity where a wide range of progress is taking place, even if somewhat more slowly and hesitantly in some areas than others (e.g. Schmid, 2011; Silke and Schimdt-Petersen, 2017).

To a degree, patchy progress is a reflection of the multi-disciplinary nature of terrorism studies. It has long been recognised within the field that terrorism studies is a strongly inter-disciplinary subject area (Silke, 2004), and while it has often traditionally been dominated by the political sciences, there have been very significant contributions from other areas, including psychology, criminology, economics, anthropology, history, religious studies, etc. (e.g. Schmid, 2011; Horgan, 2017; LaFree and Freilich, 2016). The interdisciplinary nature of the field is generally widely viewed in positive terms, helping to ensure an extensive range of perspectives and methodologies can be brought to bear. One challenge, however, is the risk of disciplinary silos developing, with researchers from one discipline being poorly aware of potentially useful and relevant findings from others.

Richard English (2016, pp. 148–149) highlighted that breaking down such silos was one of the major challenges now facing the future of terrorism research:

Sometimes, what we know about terrorism and how to respond to it can only be seen most clearly if we read along continua and across disciplines and beyond a narrowly-defined field of work. There has recently been something of an eirenic turn in the wider scholarly literature relevant to terrorism and counter-terrorism; but this is only properly visible if one reads well beyond the terrorism studies literature itself, and if one digs deeply into diverse disciplines… in order to see this scholarly insight properly, we have to read across methodological boundaries and, equally importantly, to address the problem that some people still too narrowly define the boundaries around the study of terrorism (and discuss terrorism research as if it occurs overwhelmingly in a very small set of journals and titles). Much of the best work on terrorist violence and terrorist actors is not published in terrorism studies journals, or in books with ‘terrorism’ in the title. Instead, it addresses the contextually, historically, culturally located emergence and dynamics of political violence which many would consider to be terrorism. To ignore this wider literature limits the profundity and accuracy of the conclusions that can be reached.

Adding yet another hurdle for research to grapple with is the troublesome issue of how terrorism is defined. To put it bluntly, there has never been a widely agreed definition of terrorism, and some writers have concluded that ‘it is unlikely that any definition will ever be generally agreed upon’ (Shafritz, Gibbons and Scott, 1991). The failure to find a widely acceptable definition of terrorism is tied to the political use of the word. Fundamentally, ‘terrorism’ is a pejorative term with a range of negative meanings. These concerns tie into the long-standing truism that ‘one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.’ Individuals such as Nelson Mandela, for example, were labelled as terrorists for many years, and yet Mandela went on to become an internationally respected statesman.

Terrorists rarely describe themselves as ‘terrorists’. While on trial in 1878 for shooting a Russian police general, Vera Zasulich proudly proclaimed in court, ‘I am a terrorist, not a murderer’ (Bergman, 1983), but subsequent inheritors of her legacy have shied away from the label. Instead, later generations of ‘terrorists’ portrayed themselves as soldiers, freedom fighters, volunteers, partisans or the resistance (at least in their own minds if nowhere else). Normally they were equally bitter about any effort to describe them as criminals.

The dividing lines between terrorism, guerrilla warfare and insurgency, for example, have never been clear-cut. For some, inevitably, the terms are completely interchangeable. For others there are important and powerful differences. The common thread running across all three is the use of violence for political purposes, but little else is agreed about, and many governments tend to be quick to apply the label ‘terrorist’ to an opponent if they can possibly get away with it.

Uncertainty over what terrorism is not only has political implications, but also has real consequences for research. For example, if you are interested in understanding the root causes of terrorism, one study might have a very narrow focus only exploring instances of terrorism perpetrated by lone actors; another might focus instead on conflicts which could be regarded as insurgencies or civil wars; while a third study might try to look at the state use of terrorism. All three studies might in theory be looking at ‘the causes of terrorism’, but what each means by ‘terrorism’ is very different. Inevitably, the studies come to different conclusions. Similar problems apply in terms of research on counterterrorism: exactly what type of terrorism is being countered? This is not always clearly spelt out with the inevitable result that there is often confusion and mixed findings around the impact of counterterrorism too.

Persistent concerns about the impact of how terrorism was defined within research partly contributed to the development of the sub-field of Critical Terrorism Studies (CTS) in the 2000s. Formally established in 2007, CTS argued that a variety of issues had not been adequately addressed by mainstream terrorism research. A particular concern was that research tended to see terrorism as something only non-state actors did. As Jackson (2009, p. 70) noted:

An important consequence of these conceptual practices are that terrorism comes to be understood and studied solely as a form of violence carried out by non-state groups, and terrorism by states remains unstudied and mostly invisible… When state terrorism is discussed, it is usually limited to descriptions of ‘state-sponsored terrorism’ by so-called ‘rogue states’. Further, the subsequent silence on the direct use of terrorism by state actors within the Terrorism Studies literature underpins a mostly unspoken belief that Western liberal democratic states in particular never engage in terrorism as a matter of policy, but only occasionally in error or misjudgement.

A linked concern for CTS was how:

much of the literature defines the ‘terrorist’ as the main or exclusive security problem and inquiry is largely restricted to the assembling of information and data that would solve or eradicate the ‘problem’ as the state defines it. This focus ignores both terrorism being a social phenomenon which is typically the outcome of a long dynamic process, and the potential contribution of the state itself to the creation of the conditions in which terrorist action by non-state actors occurs.

(Jackson, Gunning, and Smyth, 2007)

Controversy around the appropriate role of research with regard to terrorism is not new. Terrorism is an emotive subject, and many researchers have traditionally not been overly concerned with remaining objective and neutral in how they view the subject and its perpetrators. Indeed, it has been noted that many researchers seem confused by their roles. As Schmid and Jongman (19...