![]()

1 Meaning Beyond Syntax

Discourse and Conceptualization

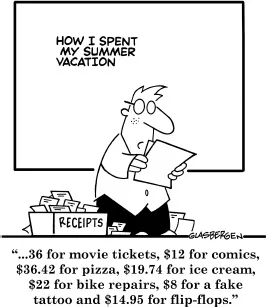

Figure 1.1 “How I spent my summer vacation”

This is a book on grammar and its relation to discourse and meaning. One of the main underlying philosophies of the book is that grammatical structures are meaningful in and of themselves and that, similar to our word choices, our grammatical choices have the power to create and communicate meaning. Even the smallest bits of grammar, like determiners a, the, each, and every, are conceptually meaningful in systematic and potentially powerful ways.

We present an approach to grammar and discourse that reveals meaning from a conceptual perspective, focusing on the ways in which users of language express viewpoints, stances, and information and depict imageries using the conceptual categories that underlie all of grammar within discourse. We introduce and work with particular grammatical categories as frameworks of meaning, often appealing to scalar conceptual notions of degree, for example, degree of individuation and specificity when referring to places, people, things, and concepts; degree of focus in picking out entities in discourse; degree of change potential in discussing events or states; degree of control over actions and outcomes; degree of intensity in descriptions; degree of personal involvement; and so forth. As you will see, much of grammar involves scalarity and gradience rather than rigidly compartmentalized categories like parts of speech and tense and aspect marking, as presented in most traditional approaches to language, both prescriptive and descriptive ones.

This book also differs from the prescriptive and descriptive accounts of English grammar in that we view grammar and conceptual meaning as integrally and inextricably linked to discourse and genre. It is within these broader contexts of discourse and genre that grammatical forms come alive and become relevant, vibrant, and meaningful, in concert with other interrelated grammatical categories and/or parts of speech. Grammar involves the choice of certain forms over other possible competing forms, each evoking a difference in the speaker’s or writer’s perspective or perception of an event, a difference in the degree of responsibility assigned to an entity active in the discourse, or a difference in stance vis-à-vis the topic or issue at hand. Grammatical choice influences how we shape, create, organize, and understand discourse within the multiplicity of discourse genres.

The book addresses individual parts of speech, like nouns and determiners, and individual grammatical categories, like negation, transitivity, and voice, as interrelated with other parts of speech and other grammatical categories and as integral components of discourse and genre. In this way, the book is designed dually to introduce the various elements of grammar as parts of coherent wholes as well as to present grammar as an all-encompassing construct of language and discourse that is present in all facets of our everyday lives. That is, unlike the traditional accounts and reference materials on grammar that isolate parts of speech and grammatical categories as independent and isolated linguistic components, the explanations and review sections in this book cycle back and re-introduce other relevant and related bits of grammar that contribute integrally to the meaning and imageries expressed in the data samples—pointing out and asking our readers to also notice, for example, how, within the discussion of adverbials, other grammatical categories like conjunctions, adjectives (including relative clauses), nouns, determiners, and verbs (and verb types) work together to depict the beautifully crafted scene in the opening paragraphs of a novel.

The traditional rules of grammar can be confusing. They seem and sometimes truly are superficially arbitrary. And they often occur as long lists of proper usages associated with one type of grammatical construction or another, followed, as we all know, by other lists that are full of exceptions. In fact, when we think of the term grammar rule, what may come to mind just as easily and just as spontaneously is the word exception, or more accurately, the plural form of the word, exceptions, because there are usually so many of them for each traditional grammar rule. Sometimes, there are even more exceptions to the rules than there are “proper usages.”

By tweaking the generalizations of the so-called grammar rules and incorporating meaning based on conceptual representations of grammatical categories and parts of speech, we re-evaluate the regularities in grammar patterns. In this way, many of the traditional exceptions are incorporated into the new generalizations. This approach to grammar is based on more flexible rules, more dynamic ones that are linked to conceptual meaning. As such, the rules become simpler, and the exceptions to those rules fewer and easier to explain.

In this book, grammar is not simply discussed from the perspectives of right vs. wrong, grammatical vs. ungrammatical, proper vs. sloppy, “good grammar” vs. “poor grammar,” and especially not from the point of view of “That’s just the way it is, because the rules say so.” Instead, rules of grammar are presented as the system of language through which speakers and writers organize thoughts, experiences, ideas, perceptions, and stances.

The book’s content and approach evolved from our nearly two decades of teaching grammar to students who enter our classes with the expectation that the term grammar is equivalent to “diagramming sentences,” “rules of word order and syntax,” and even “standards by which to judge how people use language.” Students enter our courses expecting more of the same: rules and exceptions, or what constitutes “proper” vs. “improper” structures or “right” vs. “wrong” choices. And more than that, students leave our courses and workshops with a keen sensitivity to the nuances of meaning created through choices of grammatical forms and structures and, generally, a keen sensitivity to how language is used—everywhere.

For speakers and writers, teachers, learners, and users of language, this enhanced awareness of language and discourse not only improves our skills in oral and written communication but also helps us see beyond the words, beyond the literal, and beyond the surface, while attending to choice-making and concepts, meaning and stance, within the wide range of genres and registers that permeate all of our discourse throughout all of our lives.

A simple illustration is the opening cartoon, Figure 1.1. One classic back-to-school genre of discourse is the oral report or essay in which students share what they did during their summer break. Often these essay types are reduced to cliché titles like “How I Spent My Summer Vacation.” In the cartoon, instead of describing his summer activities, the student itemizes his full list of expenses—playing on the literal meaning of the verb spend as it pertains to money and the figurative meaning as it pertains to time.

Our approach to grammar is designed to guide learners and teachers of English to become more keenly aware of meaning and its connection to grammar—from the more obvious types of distinctions like singular vs. plural or present tense vs. past tense to the more subtle ones like Has the plane from Newark arrived? vs. Did the plane from Newark arrive? and further variations in which grammatically optional adverbials appear, for example, Has the plane from Newark arrived yet? vs. Has the plane from Newark arrived already? Contrasts like these are most clearly disambiguated by examining the actual discourse and genre in which they were produced and by considering the various possible stances (or attitudes) of the speaker or writer. That is, distinctions in sentence-based examples like these cannot really be accounted for without considering the surrounding discourse. We also address, as grammar, seemingly subtle distinctions in word meanings like tall vs. high or big vs. large, and gradable adjectives like cold and cool or happy and glad vs. absolute adjectives denoting upper limits, like freezing or delighted. Most of our illustrative examples draw on actual spates of discourse from a multiplicity of sources such as public signage, emails, policy documents, classroom lectures, essays, news reports, poetry, encyclopedia entries, novels, and so forth.

With regard to meaning, we also point out in multiple sections throughout the book that literal, strictly denotative meanings of words are actually quite uncommon, since genre, context, and surrounding discourse all affect and color the meanings of words. The following quote from Lemony Snicket will illustrate:

It is very useful, when one is young, to learn the difference between “literally” and “figuratively.” If something happens literally, it actually happens; if something happens figuratively, it feels like it is happening.

If you are literally jumping for joy, for instance, it means you are leaping in the air because you are very happy. If you are figuratively jumping for joy, it means you are so happy that you could jump for joy, but are saving your energy for other matters.

(Snicket, 1999, p. 68)

For someone to “jump for joy,” literally, as the passage describes, he or she is springing upward into the air out of happiness, feet off the ground. How often have you actually (and literally) witnessed something like this? In what sorts of contexts might people literally jump for joy? Possibly, in scenarios like these:

Employees receiving a huge raise, prospectors finding gold, students on the last day of school just before summer vacation …

Figuratively, though, “jumping for joy” expresses a high degree of happiness in which a person feels like leaping into the air but doesn’t actually do it in a realistic context. Literal interpretations of language make for interesting imaginary scenarios but often not realistic ones.

If you think about the disparity in pay between male and female professional athletes, you might be opening up a huge can of worms, but not literally, of course. It just means you’d be opening up a controversial or problematic issue, one that could be immensely difficult to resolve.

The meanings of phrasal verbs change significantly with literal and figurative interpretations: You can pull your socks, boots, or gloves off, or someone’s wig can fall off. Both expressions yield a possible literal interpretation of an event. But if you laugh your head off or cheer your lungs out, there could be real trouble.

Also, meanings of words depend on context, the speaker(s), the addresse(s), and the genre(s). And, as you will see, there is no such thing as a true synonym in the sense of a word that has an exact one-to-one corresponding meaning with another word. While tall and high carry similar types of meanings with respect to verticality, they are near-synonyms at best, each evoking a distinct conceptual profile.

Therefore, an app that simply translates one language into another as a person speaks or as a dog barks is also impossible and potentially quite comical, as represented in the cartoon in Figure 1.2. The parody can be extended to some comical “translations” that result from such translation apps as TripLingo, Google Translate, and Waygo.

Every chapter of this book opens with a cartoon whose caption illustrates one of the main points that will be discussed in depth. The cartoon encapsulates the gist of the chapter (as this one does) or contains exemplars of the target function, part of speech, or grammatical category.

All chapters provide detailed discussions of the grammatical feature, category, or part of speech, together with robust examples from actual discourse data that elucidate and solidify the meanings and functions of those grammatical features.

All chapters contain sections called “Mini Review and Practice” and “Putting It All Together” that review the concepts and apply their meanings beyond the initial introductions and discussions. And Chapters 3 through 15 contain practice exercises that contain “Common Errors, Bumps, and Confusions” surrounding the target grammatical features (as well as those from earlier chapters), which are designed to help identify grammatical bumps and to then articulate ways that speakers and writers might revise or edit for more natural-sounding discourse. The chapters conclude with activities constructed to extend discourse- and genre-based practice and to deepen understandings of the concepts through pointed questions and suggestions for further development.

Figure 1.2 “Just bark. The app automatically translates it to English!”

In all, this book intends to reconceive “grammar,” not as a strict and unbendable set of prescriptive rules, but as a system of conceptual representation through which users of language evoke differences in perspective, opinion, and stance. Grammar traditionally gets camouflaged by “rules of structure” that not only determine “correctness” or “incorrectness” of utterances but also eclipse meaning—meaning that relates to conceptualizations of entities and events, of time and space. There is no such thing as equivalent synonyms in any language. A speaker’s or writer’s choice of an individual word or string of words evokes varying conceptual representations of people, objects, actions, states, habits, facts, and opinions.

Reference

Snicket, L. (1999). The bad beginning. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.