![]()

One

Introduction

The Greek word skepsis means enquiry or investigation. But a sceptic is not merely one who investigates; almost everyone does that. Sceptical investigation is distinctively shaped by the possibility of deception and error; and it is an important corrective to our credulous and sometimes gullible inclinations. In this book we shall examine the two philosophical movements – Pyrrhonian and Academic – that stretch from approximately the third century bce to the second century ce and together constitute ancient Scepticism.

Both Academic and Pyrrhonian Scepticism develop in complicated ways in response to each other and in response to their common dogmatic opponents. In order to trace these lines of historical influence and development, I present the Sceptics in the following chapters in chronological order (with the exception of Chapters 5 and 6). While it would be misleading to describe the whole of ancient Scepticism as a unified philosophical movement, the ancient Sceptics do share some family resemblances. As a general introduction, I offer a brief characterization of common argumentative strategies and concerns followed by a sketch of the historical narrative to be developed and some remarks about the distinction between Academics and Pyrrhonists.

Suspension of judgement

By the time the Sceptics arrived on the scene there were many competing and incompatible philosophical theories available. One of the central preoccupations of Greek philosophy from the Presocratics onward was to account for the variability and deceptiveness of appearances, and more generally to explain how and why things change. This led to a great deal of speculation and philosophical argument regarding the relation of appearance to reality. But on this important issue, as on virtually everything else, philosophers disagree. This fact adds considerably to the sceptic’s impression that we are not up to the task of explaining the variability and deceptiveness of appearances. Philosophers as well as ordinary people disagree with each other about virtually everything; at times we even disagree with ourselves.

The solution, it seems, must be epistemic: we need some non-arbitrary and principled way to resolve these disagreements. But even with regard to the proper method for resolving disagreements, philosophers disagree.

All of this is grist for the sceptical mill. But ancient Scepticism does not develop merely as a rejection of the aspirations and views of earlier philosophers; it also draws on them in a positive way.

Perhaps the most valuable skill the Greek Sophists (fifth and fourth centuries BCE) offered to teach is the ability to argue persuasively for or against any proposition. Protagoras, for example, claims that on every issue there are two opposed accounts (DL 9.51, see also 3.37), and that mastering his rhetorical techniques will lead to sound, practical judgement (Prot. 319a). The historian Thucydides, who is strongly influenced by the Sophists, opposes one account of events to another in order to do justice to the complexity of human affairs and to arrive at a properly cautious, and informed, judgement (History of the Peloponnesian War 1.22–23). The Sophist Antiphon teaches his students how to oppose arguments for the sake of learning to be an effective legal advocate. For his part, Aristotle counters Plato’s worry about the unscrupulous use of rhetorical power by claiming that arguing for and against an issue, and deriving opposed conclusions from the same premises, helps us to discern where the truth lies (Rh. 1.1; Topics 1.1–2, especially 101a34–36).

In general, the practice of opposing arguments was developed as a valuable means of arriving at philosophical judgements about the truth, deliberative decisions about the best course of action and forensic judgements about innocence and guilt. In many of the Sceptical appropriations of this method, however, the outcome is suspension of judgement (epochē), even if the goal is initially the discovery of truth. (However, Cicero’s later Academic version of this method marks a reversion to its originally positive employment; see Chapter 5, and further below.)

In so far as the ancient Sceptics promote the suspension of judgement, they are quite unlike other schools or movements. Normally we seek to understand a philosopher in terms of his doctrines, and the arguments he offers in support. For example, a Stoic believes virtue is sufficient for a good life, an Aristotelian believes we need some external goods in addition to virtue to live well, and an Epicurean believes nothing is worthwhile in the absence of pleasure. When studying such philosophers we try to determine what their doctrines amount to and why they believe them to be true.

We employ the same focus whether the doctrines in question are positive or negative. An atheist, for example, argues that God does not exist, or that we cannot know whether God exists. And an antirealist argues that there are no mind-independent structures in the world, or that we cannot know such structures exist. Even though we sometimes refer to such views as sceptical, we must note that the cognitive attitude expressed is not uncertainty or indecision, but rather a kind of belief: to disbelieve p is to believe that not-p. From the agnostic’s standpoint, both the theist and the atheist are mistaken. And generally speaking, from the standpoint of one who has suspended judgement, those who confidently deny are just as dogmatic as those who confidently affirm. For this reason the former are often referred to as negative dogmatists.

It is controversial whether any ancient Sceptics were negative dogmatists. Whether or not they were (which will be explored case by case in the following chapters) it is easy to see how they might have appeared to be. As far as the sceptic is concerned, no one, so far, has managed to establish a non-arbitrary, principled way of resolving the ubiquitous disputes. Every argument has so far been (or at least could be) refuted or met with an equally compelling counter-argument. If the Sceptics were so successful in refuting all arguments, it is hard to see how they could resist the negatively dogmatic conclusion that knowledge is impossible. At the very least it seems they must have believed something about our cognitive limitations, or about what we should do in light of these limitations.

Inconsistency

This suspicion is evident in the frequently raised objection that it is inconsistent to claim to know that knowledge is impossible or even to believe that we should have no beliefs. More generally, the project of rationally establishing that nothing can be rationally established seems to be a non-starter. Either the sceptic will provide reasons for this conclusion or he will not. But he would not provide reasons if he thought it were futile to do so. So he has to assume that we can rationally establish something if he is going to try to rationally establish that we cannot. On the other hand, if the sceptic offers no reasons, then it seems we can just ignore him.

We may restate this problem by considering the status of the premises in sceptical arguments. Either the sceptic has adequate justification for his premises or he does not. In either case he is in trouble. If he has adequate justification, scepticism is refuted. If he does not, then we may demand to be persuaded that his premises are true. The only way he can do this is to show that his premises are adequately justified, which again undermines his sceptical conclusion. (For more on this argument see Chapter 7.)

But the sceptic does not need to employ any personal convictions in his arguments. Instead, he may draw all that he needs from his interlocutor. Plato often portrays Socrates arguing in this manner. In his conversation with Euthyphro, for example, Socrates draws out the implications of a definition of piety that he probably does not accept himself. If we say that piety is what is dear to the gods, and we believe that the same thing is dear to Hera but displeasing to Hephaestus, we will have to conclude that the same thing is and is not pious (Euthyphro 7a–8a). Whether or not Socrates accepts any of these propositions is beside the point since he is primarily interested in testing Euthyphro. This is why Socrates elsewhere compares himself to a barren midwife who gives birth to no philosophical theses but merely draws them out of others (Tht. 148e–149a).

This style of argument is called “ad hominem”, not in the pejorative sense of an irrelevant attack on someone’s character, but because it relies solely on the proponent’s own views. It is also called “dialectical”, since the argument is essentially part of a dialogue in which one person defends his position against the other’s attack. From the sceptic’s perspective, the crucial point is that the questioner need not endorse either the premises or the conclusion of the argument. He may even remain agnostic about the standard of justification that he holds his interlocutor to.

The dialectical style of argument is a common sceptical strategy, but it is by no means a necessary feature of ancient Scepticism. Nevertheless, this strategy shows us one of the ways of responding to the inconsistency charge. If the sceptic is able to engage in his characteristic argumentative activity without committing himself to any beliefs about the efficacy of reason, the desirability of truth or some other related matter, then he will not be vulnerable to the charge of inconsistency. Since the sceptic need not believe anything he is asserting, he cannot be charged with inconsistently believing those things.

But the persistence with which the charge of inconsistency is levelled suggests either a persistent misunderstanding or that at least some Sceptics did in fact hold some second-order beliefs about the status of first-order beliefs; in other words, perhaps some of them did believe they knew that knowledge is impossible or that we should hold no beliefs. It is, after all, a short step from the observation that so far no belief has been adequately justified to the dogmatic conclusion that no belief can be justified. Academic Sceptics, in particular, have been thought to be negatively dogmatic in this way. In Chapters 3 and 4 we shall see why this claim is so oft en repeated and why it is mistaken.

Impracticality

While the charge of inconsistency presupposes that the sceptic has some beliefs, another persistent objection presupposes that the sceptic has no beliefs. Many critics argue that a life without beliefs is impractical, claiming that one must have beliefs either in order to act, or, at least, in order to act well and live a good, moral life (see Striker 1980). This type of objection is aptly described by the Greek term apraxia (inaction).

In responding to apraxia objections the Sceptics describe various positive attitudes one may take towards appearances without compromising the suspension of judgement. (We should note that in these discussions, intellectual seemings are counted as appearances along with ordinary perceptual seemings – so it may appear that the book is green, and it may appear that two arguments are equally compelling.) There is no standard sceptical account of how life without belief is possible. This is due in part to differences about the scope of epochē (how much we are to suspend judgement about) as well as the proper understanding of the sceptically acceptable attitudes that guide the Sceptics’ actions.

Despite these differences, the fact that most Sceptics were so keen to respond to apraxia objections indicates how important the practicality of scepticism is to them. Unlike most modern and contemporary varieties, the ancient Sceptics offered their scepticism as a way of life. This is in keeping with the general Hellenistic emphasis on philosophy as a set of practices or spiritual exercises (Hadot 1995, 2002). As we shall see in Chapter 2, the earliest official ancient Sceptic, Pyrrho, makes the revolutionary move of substituting the question “What must I know to live well?” with the sceptical question “How can I still live well in the absence of knowledge?”

The insistence on the viability of scepticism is in stark contrast with the way modern and contemporary philosophers often insulate their daily life from their sceptical doubts. For example, after proposing to take seriously the possibility that there is an all-powerful evil demon systematically deceiving him, Descartes calms the fears that might arise from his radical hypothesis: “I know that no danger or error will result from my plan, and that I cannot possibly go too far in my distrustful attitude. This is because the task now in hand does not involve action but merely the acquisition of knowledge” (Cottingham 1986: 15). The point of Descartes’ sceptical journey is to establish the reliability of his cognitive equipment, thereby providing a firm and lasting foundation for the sciences. And while he is convinced that scientific progress will improve the human condition, his attempt to establish its philosophical foundation is a purely theoretical matter. His scepticism is a thought experiment. He has no intention of allowing such speculation to influence his actions, and he would be utterly unimpressed by the apraxia objection.

None of the ancient Sceptics start out with the view that scepticism is an awful, if rarefied, condition that must be overcome. Ancient Scepticism is not so much a problem or set of objections as an argumentative practice situated in a philosophical way of life. And, at least for Pyrrhonian Sceptics, epochē is an accomplishment and the means to tranquility.1

The distinction between Academics and Pyrrhonists

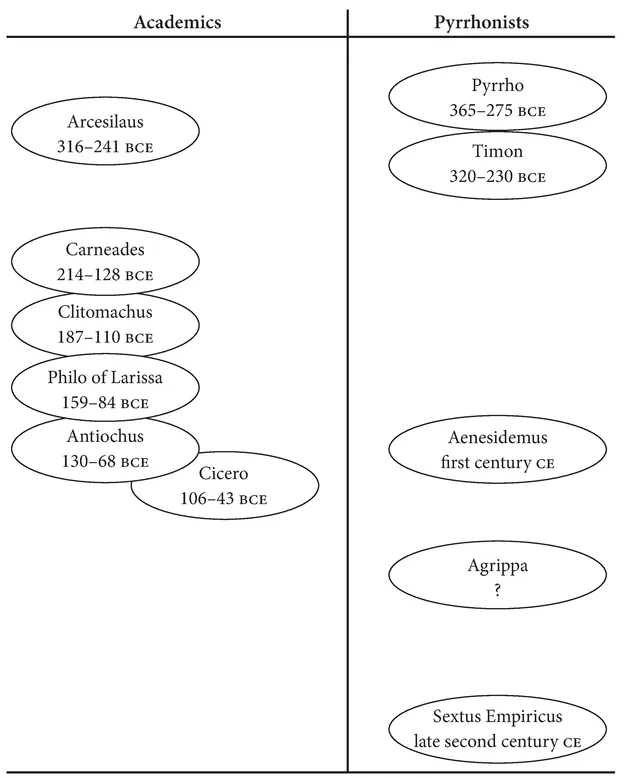

Although it is easy enough to classify the Sceptics as Academic or Pyrrhonist (see Figure 1), this sheds little light on any substantive differences between individual Sceptics or between the two camps more generally.

In the second century CE, the Roman author Aulus Gellius refers to the distinction between Academics and Pyrrhonists as an old question treated by many Greek writers (NA 11.5.6; see Striker 1981). Gellius uses the following terms to describe both Academics and Pyrrhonists: skeptikoi (those who investigate), ephektikoi (those who suspend judgement), and aporētikoi (those who are puzzled).2 As to the difference, he reports it in this way:

the Academics apprehend[3] (in some sense) the very fact that nothing can be apprehended, and they determine (in some sense) that nothing can be determined, whereas the Pyrrhonists assert that not even that seems to be true, since nothing seems to be true.

(NA 11.5.8)

Figure 1. Academics and Pyrrhonists.

The Pyrrhonian Sceptic Sextus Empiricus offers roughly the same distinction in his preliminary division of kinds of philosophy:

Those who are called Dogmatists … think they have discovere...