Language, Bi/Multilingualism, and Translanguaging

Scholarship on language education has increasingly focused on what Conteh and Meier (2014) and May (2015) have called the multilingual turn, a recognition that those involved in language education are, or are in the process of becoming, multilingual. At the same time, poststructuralist approaches to sociolinguistics (Blommaert, 2010; Makoni & Pennycook, 2007; Pennycook, 2010; see also García, Flores & Spotti, forthcoming) have emphasized not only the very diverse language practices of people in a global world, but also the sociopolitical effects that the construction of named languages like English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, and so on have had on language-minoritized populations.

The phrase “construction of named language” is used to emphasize the fact that the terms “English,” “Spanish,” “Arabic,” “Chinese,” “Swahili,” “Russian,” “Haitian Creole,” etc. name socially invented categories. These categories are not imaginary, in the sense that they refer to entities that exist in the societies that have coined the terms and have had real and material effects (like the terms “White person,” “Black person,” “alien,” “immigrant”). But these terms for named languages do not necessarily overlap with the linguistic systems of individual speakers. While someone may be recognized in society as a speaker of a particular language, each individual uses what amounts to his or her own language, which differs in ways big and small (i.e., vocabulary, pronunciation, and structure) from that of every other person who is said by the society to also speak “English” or “Spanish,” for example (for more on this, see Otheguy, García & Reid, 2015). One matter is the named language, quite another is the linguistic system of words, sounds, constructions and so forth that permits a speaker to speak, understand, read, write, communicate, and do other linguistic work. Every human being’s linguistic system is shaped by and evolves through social interaction. In some cases, when people are very close (relatives, colleagues, friends), their linguistic systems are similar because they have been impacted through their constant interaction. In many cases, the linguistic system of people who are said to speak the same named language are close enough for them to understand each other pretty well. But in others, two people who obviously have very different linguistic systems are also said to speak the same named language. For example, people from Ireland and the southwestern United States are both said to speak the named language “English,” but we know that their linguistic systems, the words and rules in their linguistic repertoire, are so different that sometimes they do not understand each other when they speak. That is why when speaking on an American TV show, an English speaker from Ireland usually gets subtitles. Notwithstanding the fact that society thinks of the two English speakers as speaking the same named language of English, their linguistic systems are so different as to preclude understanding.

Now what about bilinguals? Well, societies usually say that they have two linguistic systems, one for each named language. But is this really true? Does the person who is said by society to speak the named language English and the named language Spanish or Russian really have two linguistic systems? In the developing movement in language education that goes under the name of translanguaging, and in our interpretation, the answer is “No!” Bilinguals, to be sure, have two named languages, but that is only when seen from the social or outsider point of view. But when seen from the point of view of their own linguistic system, it is more accurate to think in unitary terms, and to assume that they have a single system. The term translanguaging should be taken in the sense of transcending, “going beyond,” the two named languages of bilinguals (English-Spanish, English-Russian, Zapotec-Spanish, etc.), or the three of trilinguals, or the many of multilinguals, and to think of bilinguals/multilinguals as individuals with a single linguistic system (the inside view) that society (the outside view) calls two or more named languages.

Origins of Translanguaging and Our Meaning

It is by now well known that the term translanguaging was coined in Welsh (trawsieithu) by an educator, Cen Williams, who developed a different approach to bilingualism in education (García & Li Wei, 2014). To deepen the students’ use of Welsh and English, students were to recast understandings received in one language in the other language. Instead of having students always use Welsh in one situation and classroom space and time and English in another, as traditional bilingual education programs do, Cen Williams’s translanguaging (1994) provided Welsh students with opportunities to change the language of the input and the output (see Baker, 2001). For example, students were asked to read in one language and write in another or to discuss in one language and read in another, and so forth.

In many ways, this original sense of the term translanguaging went beyond the ways in which practitioners had interpreted Cummins’s interdependence hypothesis (1979). Early on, Cummins posited that there was an underlying Common Underlying Proficiency between the languages of bilinguals that allowed for transfer to occur. It demonstrated how learning academic content, no matter the language of instruction, enhanced the general knowledge base of the student. Cummins’s hypothesis was interpreted in those early days as supporting bilingual education, because not everything taught through one language had to be retaught through another. Cummins’s very influential hypothesis provided the impetus for the expansion of all types of bilingual education in the 20th century, especially in North America, where immersion bilingual programs in Canada and developmental maintenance and transitional bilingual programs in the United States flourished.

At the same time, Cummins’s early work was used by educational authorities and educators to legitimate practices that were in effect, those of double monolingualism (Grosjean, 1982; Heller, 2007). The bilingual education programs that were developed towards the second half of the 20th century were either sequential, meaning that instruction was solely in one language until two or three years later, or simultaneous, meaning that both languages were introduced at the same time. Regardless of whether the introduction of the additional language was sequential or simultaneous, the two languages were always taught at separate times, for separate subjects, and/or with separate teachers who were in separate rooms. In Canadian immersion bilingual programs, Anglophone language majority children were taught exclusively in French initially until English was introduced a year or so later, eventually maintaining a 50:50 relationship with French. In Canadian immersion programs, two classrooms and two different teachers were used (Lambert & Tucker, 1972). In the United States, in the developmental maintenance programs and the transitional bilingual education programs that became prevalent after the Bilingual Education Act was passed in 1968, educators, for the most part, allocated the languages to different times, subjects, places, and/or teachers. National languages were reified as autonomous, were taught in isolation of students’ home languages, and speakers simply had to make the transfer from one language to the other. The legacy of language separation lives on in contemporary forms of bilingual education.

In effect, the translanguaging practices that were proposed by Welsh educators at the end of the 20th century were exceptions to the common practice of separating languages strictly. Within one space, children were encouraged to use the two languages in interrelationship, building a bilingual Welsh identity that did not conceive of the child as two monolinguals, but rather as one integrated bilingual. This was not the first time, of course, that educators advocated for practices other than the double monolingualism that language education programs legitimated. Rodolfo Jacobson, for example, had proposed what he called a “concurrent approach to bilingual teaching” (1990). Jacobson developed the idea that bilingual teachers would use intersentential code-switching to teach bilingual children; that is, alternating languages but only at the end of sentences. But Jacobson’s code-switching conception of alternating languages had more to do with enabling comprehension than with supporting and developing bilingualism, which was precisely the Welsh idea behind a translanguaging pedagogy.

Since Gumperz (1976), the sociolinguistic literature has increasingly shown how code-switching represents the agency of bilingual speakers to use two separate languages that represent two linguistic systems (Auer, 1999, 2005; Myers-Scotton, 2005). And educators, especially those working in post-colonial contexts, have shown how code-switching is a common practice among educators to make comprehension possible, especially in Africa and Asia where the medium of instruction is often one that is different from the language spoken by the children (see, for example, Lin, 2013a; Lin & Martin, 2005). Arthur and Martin (2006) speak of the “pedagogic validity of codeswitching” in situations in which students do not understand the lessons.

No matter how positively code-switching is conceived, both in the sociolinguistic and the language education literature, it still endorses what García (2009), following Del Valle (2000), called a monoglossic ideology of bilingualism, one that takes an external viewpoint of language and that only takes into account two named languages that are said to constitute two linguistic systems. A translanguaging theory, however, takes the point of view of the bilingual speaker himself or herself for whom the concept of two linguistic systems does not apply, for he or she has one complex and dynamic linguistic system that the speaker then learns to separate into two languages, as defined by external social factors, and not simply linguistic ones. Translanguaging, García (2009) says: “is an approach to bilingualism that is centered, not on languages as has been often the case, but on the practices of bilinguals that are readily observable” (p. 44).

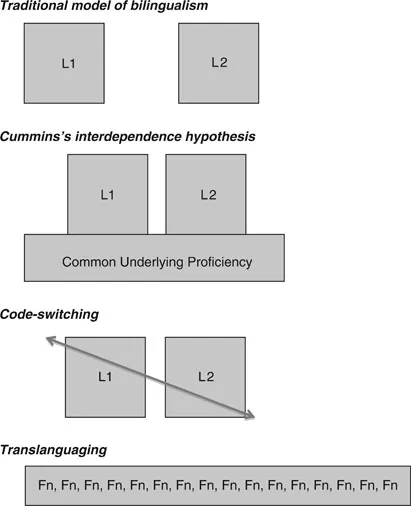

Figure 1.1 displays the differences between a traditional model of bilingualism, Cummins’s model of interdependence, a model of code-switching, and what we are naming translanguaging.

Figure 1.1 Different Models of Bilingualism

Traditional models of bilingualism consider speakers as having a first language (L1) that is separate from the second language (L2). A language education program would then require students to simply add a second language to their first, but always keeping them separate. It was this model of bilingualism that enabled Lambert (1974) to talk about “additive bilingualism” and “subtractive bilingualism.” The conception of additive bilingualism responds to two language systems that are always separate. Today many educators still refer to these types of bilingualism and their corresponding educational models, using these terms.

Cummins’s interdependence hypothesis brought the two languages closer together by positing a Common Underlying Proficiency that enabled students to transfer concepts (both academic and linguistic) from one language to the other. Cummins’s model supported the idea that bilinguals possess two separate linguistic systems, although they feed each other and are interdependent because speakers have one linguistic and cognitive behavior.

Code-switching also relies on the idea that there are two language systems, but indicates that bilinguals transgress these all the time by alternating languages that are still seen as autonomous, closed systems with their own linguistic structures. Even though the recent literature on code-switching refers to this ability of bilinguals as an important and creative resource (see especially Auer, 1999), it is still viewed as exceptional transgressive behavior. Code-switching relies on the notion of named national languages (the external view) rather than on the ways in which bilingual speakers deploy their own linguistic resources (the internal view).

In contrast, for us, translanguaging refers to the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire, which does not in any way correspond to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named languages. That is why we annotate the features (F) of the speaker’s linguistic repertoire with a nominal number (n), and we do not designate L1 or L2. The features of a bilingual’s repertoire simply belong to the bilingual speakers themselves who have one language system, and not to the languages. For example, when Ofelia speaks in her bilingual home, she uses words such as amigo, casa, room, dinner, comida, árbol, plants, building, cielo, earth, table, etc. Now, we might say that these words belong to Spanish or English as nationally or culturally defined, but for Ofelia these are simply Ofelia’s words. In speaking to her grandparents, Tatyana also uses words like TV, stroll, гулять, eat, ужин, home or дома. However, outside of her home Tatyana differentiates between those that are English and those that are Russian because she knows that not everyone shares all the elements of her linguistic repertoire. So Tatyana knows how to select the features that are socially named English from those features that are socially named Russian.

It is important to understand the major difference of our theory of translanguaging from all the other models provided in Figure 1.1. In all the other models besides the translanguaging one, language is considered from the external viewpoint of the political state and imbued with a linguistic reality that is illusory, since named languages have been socially const...