![]()

1

Early Greece: Homer and Hesiod

Bronze Age Greece

The island of Crete was one of the earliest centres of civilization in the Mediterranean. The remains at Cnossus show that the Bronze Age civilization called Minoan was highly developed and lasted from roughly 3600 to 1000 BC. On mainland Greece, a Bronze Age civilization, centred upon royal palaces such as those excavated at Mycenae, Tiryns and Pylos, developed somewhat later and lasted from about 1580 to 1120. The physical remains of these civilizations were largely unknown to the later Greeks, nor were there any written records available to later historians of the Classical period. In the opening chapter of his history of the Peloponnesian war, Thucydides, the most highly regarded of the Greek Classical historians, says that he has found it impossible, because of the remoteness in time, to acquire a really precise knowledge of the distant past or even of the history preceding his own period. In modern times the growth of archaeological science has enabled historians to fill in some of the gaps before the age of written records and also to supplement and sometimes to challenge the literary record. Examinations of burial sites and of their grave goods and of sanctuaries and their votive offerings have revealed patterns of settlement and trade. Not only do Minoan and Mycenaean pottery differ in style, but scientific analysis of the chemical composition of the pottery has enabled specialists to date it and to pinpoint its place of origin fairly precisely.

Minoan Civilization

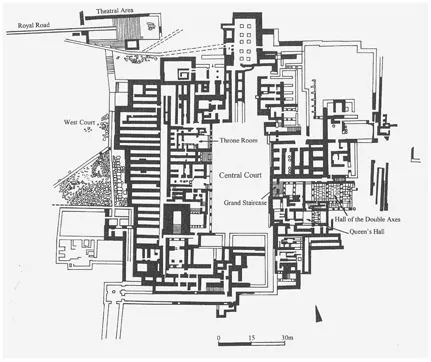

The modern world first owed its knowledge of Minoan civilization to the pioneering work of the British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851–1941) who excavated the site of Cnossus in early years of the twentieth century. He first uncovered the substantial remains of a great palace; his further investigations over a period of a quarter of a century discovered more and earlier remains, so that he distinguished various phases of Cretan civilization which have since been further refined by subsequent archaeologists after further excavations and ever more sophisticated techniques for dating ancient material remains. The several large palaces that have been excavated are not fortified, suggesting that development at Crete was largely peaceable. The largest palace at Cnossus which is highly sophisticated in its design and its decoration (fig. 1) dates to 1700, replacing a previous one destroyed by an earthquake; it covers a huge area of more than three acres and comprises a complex of labyrinthine buildings around a central courtyard with storerooms for grain and food, and workshops for potters and painters.

Figure 1 Plan of the palace at Cnossus

Evans called the civilization uncovered by his excavations Minoan because later Greek historians believed Minos had been a powerful king whose empire dominated the Cycladic islands in the Aegean, while in Greek myth Minos is the lawgiver of Crete and the subject of celebrated stories. In the most famous, Minos was a son of Zeus by Europa whom he carried off by taking the form of a bull. Minos had brothers and to settle the question as to who was to be ruler of Crete, he prayed to Poseidon, god of the sea, to send him a victim for sacrifice, whereupon Poseidon sent a bull from the sea. But Minos failed to sacrifice the magnificent animal and so Poseidon caused Minos’s wife Pasiphae to fall in love with the bull. The creature that resulted from their union with the head of a bull and the body of a man was the Minotaur. The labyrinth was constructed by the craftsman Daedalus in order to hide the monster.

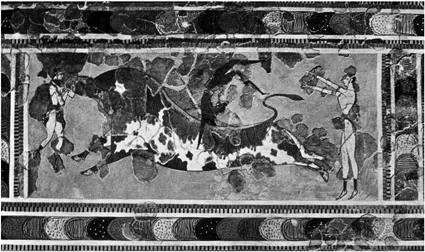

Figure 2 Fresco at Cnossus: bull-jumping

The motif of the bull is prominent on the fresco decorating the wall above the north entrance of the main palace, as reconstructed by Evans. The historical importance of the bull in Cretan life is further evidenced in one of the dynamic frescoes, which depicts the sport of ‘bull-jumping’ (fig. 2). The idea seems to have been that as the bull charged, jumpers, perhaps in succession, grabbed the horns of the bull and somersaulted over the head landing on the bull’s back. This is certainly what is depicted on the elegantly designed representation that manages to capture both the power and speed of the bull and the acrobatic agility of the jumper. The two standing figures are women, who are evidently not excluded from the society of men in what might seem the most masculine of endeavours. In their restored condition, these palace frescoes are quite stunningly beautiful. One of these (fig. 3), known as the Minoan Lady, was given the title La Parisienne by Sir Arthur Evans because it seemed to represent a stylish feminine beauty and elegance. Some of her colouring survives, notably the red on the lips, black for the eyes and blue for the dress. In its

Figure 3 Fresco at Cnossus

original condition it must have been a very vibrant image testifying to a highly developed appreciation of beauty.

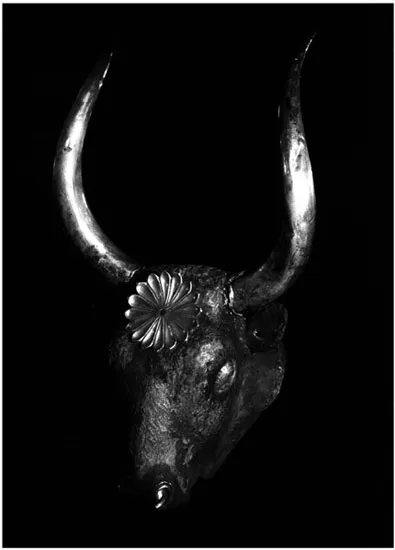

In Cretan pottery there are bull pots, that is, pots not simply with bulls decorating them but actually in the form of a bull’s head. Cretan vessels have been found in various parts of the Aegean, notably in considerable quantities at Akrotiri, an island in the southern Cyclades, which suffered a fate similar to that of Pompeii when it was overwhelmed in a volcanic eruption in 1628. At the least, this indicates thriving trading relations with neighbouring islands, though perhaps falling short of an empire. The palace at Cnossus was evidently the centre of a successful highly developed mercantile society.

Further evidence of sophisticated Cretan development is the presence of writing on clay tablets and other objects from 1800 to 1450. Not enough of this script, known as Linear A, survives for modern scholars to decipher but it is agreed from study of it that the Cretans were not Greek speaking. Many of these tablets contain numbers and are thought to be accounts and evidence of a developed bureaucracy. Some Minoan specialists have concluded that the palaces were centres that took in grain and olive oil from palace lands or from outlying farmers in the form of tax. This means the palace community of the well-to-do and their workers were supported. Surpluses were redistributed to villages and outlying communities and sold overseas. A second script starting in the mid-fifteenth century was discovered at Crete similar in its form to Linear A and so designated Linear B. This script was also discovered on the mainland at Mycenaean centres such as Thebes, Tiryns, Pylos and Mycenae itself. Linear B was deciphered in the 1950s and shown to record an early form of Greek. These Linear B tablets are all records or inventories. Their decipherment places the Mycenaeans in Crete probably as conquerors and establishes an ancestral connection between the Mycenaeans and the later Greeks.

Mycenaean Civilization

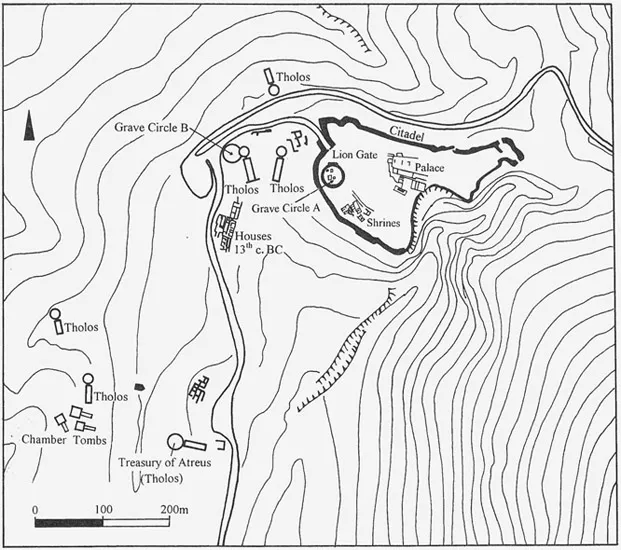

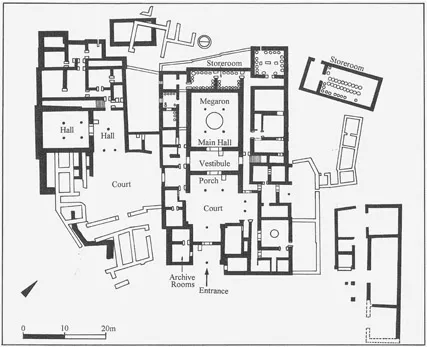

This civilization is centred upon royal palaces on the Greek mainland and is called Mycenaean after what seems to have been its most powerful centre. In Homer’s Iliad, Mycenae, called in Homer’s Iliad ‘rich in gold’, ‘well built’ and ‘broad-streeted’, is the home of Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek expedition, and the city that sends the largest contingent of ships. When he visited Mycenae in about 150 AD, Pausanias reported that it is the location of the graves of Atreus (the father of Agamemnon) and his children (Description of Greece, 2,16,6). The amateur German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann (1822–1890) first excavated the site in the 1870s, and he believed that he had found the tombs of Agamemnon’s family. Subsequent scholars have rejected his conclusion that these graves could have been contemporary with any likely date of the Trojan War. Nevertheless, the Homeric names given by Schliemann to his finds are still used today. As in the case of the Minoans, archaeologists have identified various phases in Mycenaean culture, which endured over four centuries in the different centres such as Pylos and Tiryns. The remains of the palace at Pylos, traditionally known as the Palace of Nestor, are particularly impressive and on a scale that looks comparable to the excavations at Cnossus.

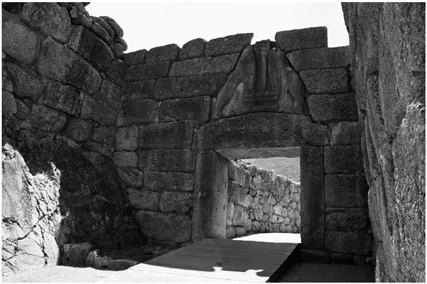

The most substantial remains at Mycenae are the finest example of early monumental architecture. The so-called Treasury of Atreus and the Tomb of Clytemnestra (the wife of Agamemnon), were built after 1300. The tombs themselves have the shape of a beehive (called a tholos in Greek); this is forty-three feet high and forty-seven feet in diameter. The great ‘dome’ has no interior buttress and its form is self-supporting, being held in shape by the weight of the stones alone. The tomb must have contained treasures but it had been plundered in antiquity. The focal point of the city is the megaron, or great hall, situated on the acropolis; it has a columned entrance and an interior room. The Lion Gate of Mycenae (so called from the relief over its lintel) that forms the entrance to the palace dates from 1250 (see fig. 6) added a century after the first fortification wall. The lions, clearly a symbol of royalty, have lost their heads, possibly because they were gilded or made of bronze. The fortification walls were mighty indeed. They were between 12 and 45 feet thick and it has been estimated they were as high as 40 feet. Mycenaean culture is generally thought to have been more warrior-based than the Minoan which flourished primarily through trade. Certainly no comparable defensive structures have been discovered on Crete. Nevertheless, remains of Mycenaean pottery are widespread in the Mediterranean world, indicating that the Mycenaeans, like the Minoans, were great sailors and traders. The Linear B tablets discovered at Mycenae and other Mycenaean sites such as those at Pylos, Tiryns and Thebes, also indicate a highly organized administrative system akin to developments on Crete.

Figure 5 Plan of Nestor’s palace at Pylos

The treasures found by Schliemann in the royal graves at Mycenae which date from the sixteenth or fifteenth century and include the famous gold face masks (see fig. 7), bear witness to the opulent beauty of Mycenaean artwork, which was highly sophisticated in craftsmanship and design. The techniques of engraving, enchasing and embossing were well developed and so was that of inlaying bronze with precious metals. Ivory and amber imported from the east and the north are commonly found and indicate the extent of Mycenaean commercial relations. The handsome silver vessel for making libations, called in Greek a rhyton (fig. 8) in the shape of a bull’s head with magnificent gold horns, discovered in a grave circle into which it was doubtless put to honour a great hero or king, has been beautifully crafted by hammering the metal from the inside. It is Minoan in conception and design and its presence among these Mycenaean treasures two centuries before the fall of Cnossus in 1400, whether it was inspired by a Cretan original, copied or imported, suggests a long-standing cultural connection between Crete and the Greek mainland. After the destruction of Cnossus in 1400, Mycenaean civilization was at its most powerful and advanced and it seems to have lasted for a further three hundred years until its collapse just before 1100.

Figure 6 Lion Gate, Mycenae

Schliemann’s excavations at Mycenae came after his earlier excavations at Hissarlik in northern Turkey, which he believed to be the site of Troy. Excavations here have recorded nine settlements, the seventh of which was destroyed by a great fire in the mid-thirteenth century, so that archaeological evidence might seem to lend support to the possibility of a historical Trojan War of which the Homeric account records the distant poetic memory.

Figure 7 Gold face mask of Agamemnon

The Dark Age

Soon after the possible date for the sack of Troy came the collapse of the mainland centres of Mycenaean civilization; the Bronze Age gave way to the Iron Age and ushered in what has been called the Dark Age lasting from the eleventh to the eighth century. The great palaces were destroyed and not replaced. Settlements became smaller and fewer. The use of Linear B was lost. There was a general decline in art and craftsmanship. The reasons for this collapse have been much debated. The Greeks

Figure 8 Rhyton in the shape of a bull’s head, Archaeological Museum, Athens

themselves talk of Dorians invading from the north but archaeologists have not found convincing evidence of a mass takeover by invading peoples. Other explanations involve some natural catastrophe or internal conflict or both in conjunction with external attacks.

The general picture of life in Dark Age Greece has been one of impoverishment on all fronts. However, recent excavations at Lefkandi on the island of Euboea have revealed a substantial and prosperous settlement that is so far a single exception to this general rule. Artefacts have been found dating from the early Mycenaean period down to about 800. Excavations have turned up fine examples of Levantine pottery and Phoenician bronze bowls indicating contact with the outside world thought until recently to have been lost in this period. But the most interesting finds are the remains of a large building dating from about 950 and built in a style different from anything Myceneaean but anticipating the first temples of some two hundred years later. In one of its rooms are two pits, one containing the skeletons of four horses and the other the cremated remains of a man in a bronze urn decorated with a hunting scene. His iron sword and spearhead lay nearby. Also nearby is the skeleton of a woman laid out with feet and hands crossed and decorated with items of gold jewellery. Scholars have drawn parallels with burial customs elsewhere, notably with those performed in the final book of Homer’s Iliad for Patroclus who is cremated with his horses and with the human sacrifice of Trojan youths, though here the woman may be a wife who died from natural causes and was subsequently buried with her husband. The figure was evidently a man of substance and power, leading to speculation about the social order of this p...