![]() PART I

PART I

HISTORICAL AND THEORETICAL INTRODUCTION TO THE EURO![]()

Chapter 1

Historical and Theoretical Considerations

This chapter uses a new regionalism approach to examine how the introduction of the euro has affected the so-called “new world order” in the twenty-first century and how the current economic crisis and financial uproar is affecting both the new order and the tenets of the new approach.

The introduction of the euro created the Eurozone, a new region considered a supranational or world region with an important role in the current global transformation. The euro has demonstrated that although it was introduced as an economic tool for integration, it has a political, social, and cultural dimension. Thus, the euro has become a multidimensional form of integration because the actors behind integration are not only states, but also a large number of institutions and organizations with the political desire to strengthen regional coherence and identity. The Eurozone should be considered the core region because it is economically and politically dynamic and structured and the rest of the European Union (EU) and non-EU members relate to it. Particularly, this chapter explains how, under new regionalism, the Eurozone and the euro have helped increase not only economic, but also political, social, and even cultural homogeneity respecting diversity.

Further, this book reflects that the current economic crisis and financial uproar has affected the new regionalism trend that began in the 1980s with the political and economic integration efforts in the EU and the Eurozone. The current economic events are affecting the integration process in the EU and the Eurozone in two dangerous but interesting ways. On the one hand, the economic crisis has negatively affected to different degrees the economies of some countries such as Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain. In particular, Greece, Spain, and Portugal are in financial and economic positions that are halting the integration program, particularly financial and economic integration. On the other hand, these economic difficulties are pushing certain countries to look inward in a sort of defensive mechanism. Such is the case of Belgium, the UK, and in Spain, where national nationalism is suddenly being revamped and is now becoming more skewed than ever as the economic situation is getting worse. As a consequence, countries that were in line to adopt the euro are rethinking their view on becoming part of the Eurozone. Mainly, the impossibility of using monetary policy as a method of adjustment in the event of deep monetary problems, added to the lack of coordination among Eurozone Member States on how to tackle the current crisis, has also made certain countries wanting to join the EU and the Eurozone change their prospects. Furthermore, the current crisis has affected other integration projects such as Mercosur and the African integration. However, Asian countries seem to be immune and January 1, 2010 has become a milestone date because it was the beginning of the China-ASEAN Free Trade Area. This agreement, which has an economic purpose in mind, is a “breeze of fresh air” for models for regional unity because “today, the free trade area is of greater significance amid the ongoing global financial crisis and rising trade protectionism when developing countries are more vulnerable because of their fragile economies.” (People’s Daily Online 2010)

Finally, this chapter introduces an overview of the rest of the book’s contents and presents the book’s research design and methodological approach, because this book uses a number of time series and statistical approaches to strengthen its findings in order to provide the conclusion with a solid theoretical and statistical foundation. Also, Chapter 1 explains what have been the technical and theoretical difficulties found along the way. This chapter explains that the EU and the Eurozone suffer from an important lack of time series availability and variety. The fact that it is complicated, at best, to find the same time series for a number of countries in the same time frame and period of time makes any quantitative analysis complex.

The Twentieth Century: Regionalism and the New World Economic Order

The twentieth century witnessed dramatic changes in the state and nature of government and governance. This century endured two major world wars, a cold war, a major economic recession, and a number of minor ones. However, all these events seem to have taught that conflict and confrontation result in nothing but social misery and economic pauperism.

Thus, although the first half of the century witnessed two world wars, the second half of the century put to work the lesson that cooperation is more productive than destruction. In particular, the end of the Cold War and the first stages of globalization made a number of geographically closed countries realize the benefits of cooperating and coordinating economic strategies to find synergies in a non-zero-sum game. The devastation of World War II and the economic situation in which most of world’s nations were immersed required the arrangement of the economic system, beginning with the urgency for fixing dangerous imbalances in the currency system in order to control currency fluctuations and allow commerce to flourish.

After World War II, the world had to be completely reconstructed. The regionalist approach provided the right set of tools because, according to Wallis, regionalism was characterized for being all about government, structures, coordination, and power. For instance, regionalism was oriented towards empowering any one government with the mandate to “construct” and defend the nation while the world was going through one of the most turbulent periods of history. Regionalism was concerned about developing the public sector to create a backbone of government, which consequently was necessary to establish structures. The devastation of the two wars had left nations and governments with almost no structure, and it was necessary to spend resources on the creation and organization of much-needed government and country structures for the efficient functioning of nations. Furthermore, regionalism was closed because it was concerned with defining boundaries and jurisdictions that ranged from the delimitation of national borders to the design of economic, political, and social policies that needed to be implemented. As a consequence, it was clear that countries were looking to coordinate how to best implement those policies, and as Allan Wallis (n.d., 4) explains, “coordination typically implied hierarchy; for example, a regional authority with powers to determine the allocation of resources to units of government within its boundaries.” Finally, all these four factors required accountability, which is a way of analyzing if the established goals have been accomplished and implementing corrective measures if they have not.

A number of economic and monetary systems were put in place, and although none worked out completely satisfactorily, they were all stepping-stones rather than stumbling blocks and contributed to the need for cooperation at the economic and monetary level in order to strengthen synergies to enhance governance, government, and the living standard of the population. Thus, attempts at the monetary level unveiled the advantages of monetary and economic integration.

The first stepping-stone that led to regionalism was the creation of the Bretton Woods System (July 1944–August 1971). During Bretton Woods, European currencies were under control because countries participating in the system signed an agreement in which national authorities were to submit their exchange rates to international disciplines. This system bolstered coordination and planted the seed for further cooperation and the beginning of regionalism. Under the Bretton Woods System, the US dollar was the numeration of the system, or the standard to which every other currency was pegged; this meant that other currencies were to peg their currencies to the US dollar and maintain market exchange rates within ± 1 percent of parity. At the same time, in order to bolster faith in the dollar, the US agreed to link the dollar to gold at the rate of $35 per ounce of gold. When the US economy began to weaken, loss of confidence in the dollar prompted other countries to redeem their dollar reserves for gold, further weakening US exposure. F.W. Engdahl (2004, 140) explains that “at the end of 1967, international holders of dollars went to the New York Federal reserve Gold Discount Window and demanded their rightful gold in exchange.” De Gaulle’s economic adviser, Jacques Rueff, went to London in January 1967 with a proposal for raising the price of gold, which would in turn mean the devaluation of the US and UK currencies. Washington refused to change the $35 per ounce official valuation of gold. Because the US was neither going to exchange dollars for gold nor change the gold valuation, France, the country that had most requested to redeem dollars for gold and was one of the largest holders of gold, withdrew from the system. Nonetheless, Engdahl (2004, 142) explains:

France itself was the target of the most serious political destabilization of the postwar period. Beginning with the leftist students at the University of Strasbourg, soon all of France was brought to a chaotic halt as students rioted and struck across France. Coordinated with the political unrest (which, interestingly, the French Communist Party attempted to calm down), U.S. and British investment houses started a panic run on the French franc, which gained momentum as it was touted loudly in Anglo-American financial media. The May 1968 student riots in France were the response of the vested London and New York financial interests to the one G-10 nation which continued to defy their mandate. Taking advantage of the new French law allowing full currency convertibility, these financial houses began to cash in francs for gold, draining French gold reserves by almost 30% by the end of 1968, and bringing a full-blown crisis in the franc.

Under the Bretton Woods System, Germany’s industry became the most efficient and competitive sector in Europe, and its economy became the leader among those of other European nations. The secret of this success rested in Germany’s industrial ability to take advantage of increases in demand within its borders and within most European countries by maintaining strong productivity growth while keeping labor costs from rising and achieving sound export competitiveness. As Germany’s export surplus began to grow, becoming a national symbol of monetary and economic performance, economic imbalances began to surface for other European countries. In fact, most European “firms constructed their growth strategy mostly on extracting productivity growth without much investment but by using existing capacity” (Halevi 2005, 4). Germany, instead, would use those surpluses to modernize its industries, which helped to develop new products and improve productivity.

The Bretton Woods System worked well as long as the US economy remained strong and countries agreed to hold dollars on the basis of their value in gold. Unfortunately, in the 1960s, due to the decline in the US’s balance of payments position, the system began to collapse. As a result, there was an oversupply of dollars held by foreign banks, and countries were less willing to hold dollars. These countries soon began to redeem their dollars for gold, resulting in a fall in gold reserves and an increase in the gold price. In August 1971, President Nixon announced that the US would no longer exchange dollars for gold, and the US dollar was removed from the Bretton Woods gold standard.

After the collapse of Bretton Woods, currencies opted for a system of floating rates. However, this system soon proved not to be beneficial. In an attempt to restore order to the exchange market, ten leading nations made up of the European Economic Community (EEC) Member States, as well as the UK, Ireland, and Denmark, met at the Smithsonian on December 16 and 17, 1971. This partnership marked the first step in regionalism. Two days of negotiations resulted in a new system of exchange-rate parity that was called the “Smithsonian Agreement.” As Daniels and VanHoose (2004, 12) explain, “Although this new system was still a dollar-standard exchange-rate system, the dollar was still not convertible to gold.” Unfortunately, the Smithsonian Agreement collapsed within 15 months and a de facto system of floating rates emerged. The reason for this collapse is explained by Mundell (2003, 12) as follows:

The US monetary policy was expansionary in the 1972 presidential election year and the balance of payments deficit built up large dollar balances in Europe and Japan. In February 1973 the U.S. raised the official price of gold to $42.22 an ounce (where it remains to this day). This devaluation only served to whet the appetites of speculators and the crisis intensified. The market price of gold soared and exchange markets became turbulent.

After the collapse of this agreement, European countries realized that they really needed to seek currency stability and independence from the US dollar. This time they signed the Basle Agreement, on April 10, 1972, which had been designed as an intervention system of the central banks. This intervention system, commonly known as the “currency snake,” limited fluctuations between currencies and the US dollar to a maximum of 2.25 percent and fluctuations between any two currencies participating in the snake to a maximum of 4.5 percent.

Unfortunately, this system failed mainly because economic events, led by US dollar fluctuations, made it impossible for the majority of currencies in the snake to remain within the fluctuation bands. Members participating in the snake were constantly leaving and entering. For example, the UK and Ireland left the snake in June 1972; Italy left in February 1973; and France left in January 1974, rejoined in July 1975, and left again in March 1976 (Schwartz 1983). By March 1973, only Germany and the Benelux countries remained in the snake system, underscoring once more the cohesion of the FRG economy and the strength of the D-mark. Furthermore, these events demonstrated that those countries that were not inclined to pursue price stability to avoid inflation were doomed. The lesson learned was that in order to have currency stability, countries must follow a uniform monetary policy. Consequently, Germany’s Helmut Schmidt and France’s Valéry Giscard d’Estaing did not give up on the dream of engineering a united Europe. To ensure currency stability, they originated the European Monetary System (EMS).

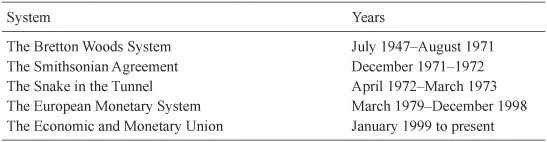

Table 1.1 summarizes the dates of the various arrangements discussed above.

Table 1.1 Monetary system date overview

The Twenty-First Century: New Regionalism and the Current Economic Crisis and Financial Uproar

At the time of writing (January 2010) the EU and the Eurozone are facing a difficult period. It seems that suddenly the integration process—widening and deepening—has come to an abrupt halt. On the one hand, there are no more countries “waiting in line” to join the EU, which gives a sense of emptiness. On the other hand, it seems as if the Lisbon Treaty impasse has stalled the deepening process, because there has been scant progress in integrating the EU in areas such as security, defense, immigration, and social policies. In addition, the four freedoms are still not fully implemented, and economic integration has not been accomplished. This situation has been worsened with the economic crisis and financial uproar that has made certain actors wonder about the EU project, particularly because economic and monetary integration successes have been the fuel necessary for the EU and the Eurozone to continue moving forward. The Lisbon Treaty impasse was the result of an implacable economic situation in Ireland that let society reject it, and in the UK, the vision of the euro changes with the economic difficulties of the country. Currently, the UK is facing one of worst recessions in history, and the actual position is that 75 percent of the population would reject adopting the euro (Tax Payers Alliance 2009). Finally, the current economic situation in Greece and the necessity for implementing harsh budgetary reforms are causing social upheavals and many complain about the prudence of remaining within the Eurozone and the EU.

David Marsh (1993) explains that the European Monetary System (EMS), introduced on March 13, 1979, became the ultimate plan designed to obtain monetary cooperation among members of the European Union in order to finally provide the currency stability necessary for the introduction of a common currency. In order to achieve this goal, Member States had to work towards synchronizing their economies in many areas, which increased their feeling of belonging to a group. Because European countries trade more with each other than with the rest of the world, it made sense for them to transcend currency fluctuations and transaction costs in order to allow trade to flourish even more. As a consequence, the EMS came into effect in 1979 with the blessing of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), which wanted to ensure its export grounds and surpluses by putting European currencies under the control of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) (see Table 1.2). The EMS became a successful mechanism and was operative until December 31, 1998 when Member States fixed their currencies to the euro. The introduction of the EMS in 1979 launched many economies further into an expansionary economic cycle that boosted productivity, exports, employment, internal demand, and investment in both equipment and construction. This has been considered the new regionalism approach in action.

Despite many setbacks, neither the political nor the economic project of a united Europe were abandoned, and the first stage of the Economic and Monetary Union’s (EMU) adoption of the euro was eventually introduced on July 1, 1990. With the introduction of the EMU, the D-mark became the anchor currency and the Bundesbank became the de facto central bank for the other countries because it was doing the best job of keeping inflation low. The problem arose due to the strength of the German economy and the low-inflation policies of the Bundesbank, which ultimately forced other countries to follow its lead. Countries were able to follow the Bundesbank but, by the mid-1980s, were driven to use changes in interest rates to maintain their currencies within the bands. However, at the beginning of the 1990s, the EMS was strained by the differing economic policies and conditions of its members, particularly those of the newly reunified Germany, and a revision of the EMS requirements was necessary. The Brussels Compromise, in August 1993, awarded the EMS with a new fluctuation band of ± 15 percent.

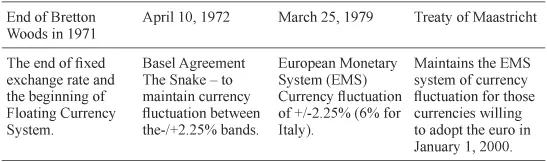

Table 1.2 Summary of monetary evolution from the Bretton Woods System to the European Monetary System

Despite all the ups and downs, the EMS worked well. Most importantly, the EMS ended with the imposition of rigid bands, which never helped to stabilize the currency, but rather attracted currency speculators. However, the EMS did help stabilize the currency to the point that—in the mid-1980s, when Jacques Delors became President of the European Commission—the momentum was perfect for the creation of the common currency. With the introduction of the euro, regionalism and its proposals made a step forward to a new regionalism approach.

The new regionalism approach better explained the necessity to promote even freer trade and economic integration, because it was proven that regionalism had positive political effects. New regionalism has been called a “halfway house between the nation-state and a world not ready to become one” (McMahon and Baker 2006, 3). Allan Wallis stated that the interest in a newer version of regionalism was the result of the globalization of the economy that at the end of the Cold War allowed for “international trade agreements, like NAFTA, and the development of a European Community all demonstrate reduced economic competitiveness on a country-by-country basis, and increased competitiveness on a region-by-region basis.” This new approach was strengthened with the creation of the European Community and all the integration efforts it conveyed. The new regionalism approach explained that

trade and broader economic integration has created a European Union in which another war between Germany and France is literally impossible. Argentina and Brazil have used Mercosur to end their historic rivalry … Central goals of APEC include anchoring the United States as a stabilizing force in Asian and forging institutional links between such previous antagonists as Japan, China and the rest of East Asia (Bergsten 1997, 1).

In fact, new regionalism is, according to Fredrik Söderbaum (2003, 1), “characterized by its multidimensionality, complexity, fluidity and non-conformity, and by the fact that it involves a variety of state and non-state actors, who often come together in rather informal multi-actor coalition.”

According to Allan Wallis, the new regionalism approach is characterized by five key elements that perfectly well explain the foundation of the EU and the Eurozone. First of all, the European project is fundamentally concerned with governance, because the main role of institutions such as the European Central Bank or the European Commission is to set the goals of what must be accomplished, establish the rules, and implement the regulation necessary to achieve these goals. Furthermore, these goals are achieved through the implementation of a process. In fact, in order for countries to join the EU, it is necessary that certain objectives are met, which requires the implementation of a process rather than mere structures. Also, recommendations on certain structural reforms—for example, labor market reforms—advise the introduction of a number of processes intended to improve employment rates. Second, new regionalism is concerned with open boundaries, a concept implied in some of the policies that have been pooled from each nation, as well as the concept embedded in the four freedoms so characteristic of the EU. Third, new regionalism entails collaboration, a trait found in most of the Treaties and Directives, the Lisbon Agenda, or even in the newly introduced Europa 2020. Collaboration means canceling all coercive measures, which annuls the need to implement the necessary structural reforms because they can be implemented as collaborative rather than as punitive measures. This goes hand in hand with the fourth characteristic of new regionalism: that Member States operate on a basis of trust and not accountability. This means that Member States are trusted to implement the recommendations and not held accountable if they do not. For inst...