eBook - ePub

Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau

Steven R Simms

This is a test

- 383 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau

Steven R Simms

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Written to appeal to professional archaeologists, students, and the interested public alike, this book is a long overdue introduction to the ancient peoples of the Great Basin and northern Colorado Plateau. Through detailed syntheses, the reader is drawn into the story of the habitation of the Great Basin from the entry of the first Native Americans through the arrival of Europeans. Ancient Peoples is a major contribution to Great Basin archaeology and anthropology, as well as the general study of foraging societies.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau de Steven R Simms en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sozialwissenschaften y Archäologie. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

The Ancient World of the Basin-Plateau

The slice of time fictionalized in the Prologue belongs to a world obviously different from our own. It is different not just because people were “hunters and gatherers” and did not have automobiles, shopping centers, health care systems, armies, and schools. The differences are more fundamental and found in the arrangements and meanings of kinship, in the workings of politics and economics, and in worldview itself. The differences are not specific to comparisons of American Indians vs. modern Americans but are found in every comparison of simple and complex societies across the planet.

Life was not necessarily hard in small-scale ancient societies, and the word “primitive” is inappropriate, because depending on your point of view, aspects of modern American culture might just as easily be dubbed “primitive.” Nor was life in foraging societies a relentless and desperate quest for food. The people’s work patterns were deliberate, informed, and structured. They had in some ways more free time than we do and like us, they had their trials and failures. Like people today, the ancient foragers of the Basin-Plateau shaped the world around them and in turn were shaped by the consequences of their choices. Like today, the “environment” consists of other people and the organizations of their behavior, not just the physical and nonhuman environment. Human culture is shaped by the twin forces of material circumstance and the historical hand we are dealt by those who preceded us.

The goals of this book are to describe what ancient life in the Basin-Plateau was like and explain why it happened the way it did. To do this, we need to “let the present serve the past” by employing a modern baseline of native cultures.1 Baselines must begin somewhere; hence the idea of “contact” between the indigenous Native Americans and the Europeans to mark a beginning. In space, our baseline is anchored by the Wasatch Front of northern Utah.

Identifying a baseline risks casting precontact cultures as monolithic and changeless before the intrusions of history altered them from their “pristine” state. We will find that the economic moniker “hunter-gatherer” takes many forms and that it includes a great deal of cultural diversity. Moreover, for more than 1,000 years, over half the Basin-Plateau region was dominated by farming societies, not hunters and gatherers. Despite the utility of a cultural baseline, it is impossible to know the ancients by simply projecting historically known cultures backward in time. This chapter provides some guidelines for knowing the peoples of the past as diverse, dynamic, and sometimes quite different from the native cultures of the past two centuries.

Finally, we extend our baseline from the Wasatch Front outward, not only to the region but to surrounding regions and the continent as a whole. This is important because in order to know why things happened in the Basin-Plateau, we need to know what happened elsewhere. Despite the seeming remoteness of the mountains and the deserts, the Great Basin and the northern Colorado Plateau were part of a “spiral of contexts”—an interconnectedness of local, regional, and even continental contexts, historically linked through vast amounts of time.

NATIVE CULTURE BEFORE THE HORSE

All of us are familiar with images of horse-riding Indians who lived in tipis, hunted bison, shot bows and arrows, and wore buckskin clothing. These images are steeped in history and are based on the eyewitness documentation of Native American life by Euro-American explorers, pioneers, writers, and scholars. This knowledge is rich and vivid, and it is part of the traditions of contemporary Native Americans in the Great Basin and on the Colorado Plateau.

Horses were introduced to the eastern Ute in Colorado in the A.D. 1600s via the Spanish entradas to New Mexico. Horse adoption likely preceded the direct arrival of European visitors to the Northern Ute and Northern Shoshone, diffusing among the native Utah groups as early as A.D. 1700 and clearly by the mid to late 1700s. The horse reached the Wasatch Front before A.D. 1776, when the Dominguez-Escalante expedition visited villages of Utah Lake Ute near modern-day Provo. They had no horses but told the Spaniards that they feared the “Cumanches,” horse-mounted peoples to the north. The Spaniards did not see the Salt Lake Valley, but the Utah Valley Ute described a “peaceful” people living around Great Salt Lake (Shoshone), with a lifestyle similar to their own and owning no horses.2

Horses brought fundamental change to how people obtained food, where they lived, and how they associated, married, led, and fought. Horses symbolized a suite of other changes brought by the associations of Europeans and natives, and natives with or without horses. The changes fall into three conceptual categories: sociopolitical, epidemiological, and demographic.

The effects of sociopolitical change are well documented, and for the Northern Ute and Shoshone they involved trading, especially the slave trade and raiding introduced by the Spanish. The new markets changed the organization of labor, leadership, and the interactions among tribes. The Ute of Colorado raided the more remote western groups of Ute in northern Utah, and by A.D. 1750, even Plains tribes were getting involved.3

These contacts provided vectors for European-introduced diseases, such as smallpox and measles passing among concentrations of indigenous groups. Since using horses promoted mobility and periodic large gatherings of people, the effects of disease were likely significant, albeit difficult to fully document, because they appear to have occurred prior to direct European visitation and eyewitness accounts.4

The adoption of horses changed basic patterns of Indian life in only a few years, but we must remember that individual elements and strongly connected patterns of the previous life remained. Cultural change may tear the fabric of a society but rarely dissolves it completely. For instance, the people continued to harvest native plants, but those filled a different niche in the diet. The native pharmacopoeia was surely the same. Many of the same places were used, albeit in different ways. Time depth is apparent in some of the themes and characters of folklore.5 Characteristics of social organization among the historic native cultures also give us some connection to a deeper past, or at least some analogies to point the way.

By the 19th century, only pockets of people remained who could help us glimpse the old world, and even in those cases, they had firearms and had been forced into the most marginal areas by Euro-American encroachment or by other Native Americans. By the early 20th century, when anthropologists set out to systematically reconstruct the precontact cultures, the memories of the few old people living in small enclaves of indigenous culture were fading. The extent to which these glimpses of life before the horse and tipi apply to the deep past is a matter of debate, but the classic ethnographies provide a rich accounting from informants who lived the “old ways.”6

Anthropology extends this record by contributing evidence from hundreds of foraging societies and simple farming societies documented around the world in recent history. Many of these societies are classified as bands and tribes by anthropologists. Bands are the simplest form of human society. A band comprises a small group of kin related by blood and by marriage, often formed into clans that trace descent to a perceived common ancestor. Leadership is based on skills and charisma, bands have little economic specialization, and their population typically numbers a few hundred people often scattered over large areas. Tribes are associations of bands and signify that hunter-gatherer societies did exhibit complexity at times—greater economic specialization and differences in wealth and power among individuals, families, and clans.

The world’s cross-cultural sample reveals that there are strong regularities in the way band and tribal societies are organized socially, politically, and in worldview and ideology. This knowledge complements the information we have from our local historical and ethnographic records that describe the Native American cultures of the Basin-Plateau region.

The following sections of the chapter break native life before the horse into categories often used by anthropologists. We begin with tangible things such as technology and economics. These things shape people’s food choices and how people moved across the landscape—two things archaeologists can usually see. The material foundations of cultures shape the abstractions of social life and the life of the mind; hence, these sections follow. They are more difficult to find in the archaeological “record.”

The archaeological record includes the artifacts, their context, the remains of houses, hearths, refuse dumps, burials, and places where they hunt, collect plants, and find toolstone—places of resource extraction. Each of these kinds of places is a signature of the past. Mostly though, the archaeological record consists of the patterns created when thousands of sites and tens of thousands of artifacts are studied in systematic ways. Our excursion here, then, through the ethnographic and historical evidence for native life, is taken with an eye for what might be relevant for the archaeology. The following sections provide some analogies to help us step into a foreign past.

TECHNOLOGY

Technology determines how people get their groceries and their raw materials, and this fact holds regardless of whether food is taken with bow and arrow and nets or is dependent on the flow of oil that fuels modern agriculture around the world. The suite of food options that Mother Nature presents to foraging cultures, and the seasonal availability and their cost of acquisition, shapes where people live and in what size of a group. The patterning of settlements, where they are, their size, and how long they are used between moves are crucial to shaping human interactions—kinship, status, role, and the politics of alliance and conflict. Technology, subsistence, mobility, and settlement are thus entryways to describing the ancient lives and cultures.

The indigenous technology of the Basin-Plateau region is ingenious, and it is one of the most simple found anywhere in the world. For the first few thousand years after the first people arrived to the region over 13,000 years ago, the stone-tipped thrusting spear was the primary large weapon. It is not known if the earliest spears were assisted by the atlatl, or spear thrower, but by 8,000–9,000 years ago, the atlatl was clearly present and caused a shift from large tipped spears to smaller tipped “darts.” This technology persisted for millennia until the bow and arrow entered the region between A.D. 0 and 500. These were the primary changes in weapon technology in the prehistory of this area until the introduction of firearms.

Atlatls and darts, and the bow and arrow, are only the most obvious food acquisition technologies. An array of gear aided the capture of small or specialized prey, including snares and traps, nets for fish and rabbits, throwing sticks, and slings. There were decoys, such as woven cattail duck decoys covered with duck skins. Pronghorn (antelope) head-dresses served the dual purpose of decoying these curious animals while enhancing the power of the shaman who “charmed” the creature into proximity.

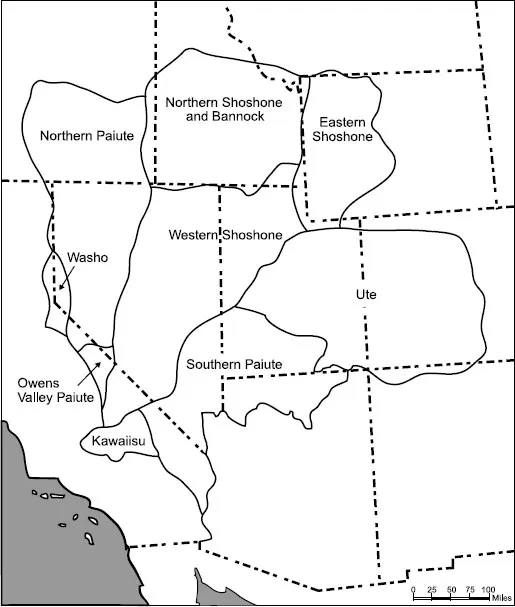

FIGURE 1.1

Map of the Basin-Plateau region showing historical tribal-linguistic boundaries.

Chipped-stone technology varied in style and specialization over the millennia, but the tool kit always included knives, drills, gravers, chisels, and scrapers; many of these objects were hafted to handles. There was a variety of handheld or hafted tools designed for wood and bone working, hide preparation, plant harvesting, and fiber cutting.

Wooden and bone tools were also used for wood shaping, for burnishing, and as wrenches and digging tools. Perhaps the single most utilized tool in the region’s prehistory is the wooden digging stick, necessary for the many kinds of roots taken. Tools for grinding were just as important as the chipped-stone dart tips or arrowheads, because plant foods were the foundation of the diet.

Flat grinding stones called metates and handstones called manos were made of basalt, rhyolite, quartzite, and even soft rocks, such as sandstones. These tools were used to mill seeds into flour, hull pine nuts, pulverize roots, and puree vegetables. They also served to grind medicinal roots, minerals, and pigments. Mortars and pestles, long cylindrical hullers, shaft straighteners, stone balls, and v-edge cobbles were some of the other forms in the ground-stone tool kit.

One of the most important technologies was the fiber industry. Without looms, all cordage and fabric had to be twisted by hand, and woven, largely with awls. Most clothing was likely made of fiber. Basketry was fundamental to life from the earliest occupants of the region to historic times. Basketmaking requires astounding skill that could be transmitted only by a master teaching an apprentice, and this skill was passed down over generations. Basketmakers knew the proper cultivation and harvest of willow and other raw materials, skill in the manufacture of basketry, and they made special tools required by the industry. Both twining (woven) and coiling (wrapped) construction techniques were richly developed in the Basin-Plateau region, with coiling increasing in frequency after about 10,000 years ago. Coiled baskets improved the mass processing of small seeds and the transport of water in pitch-lined jugs. In later periods, a special basketry tool, the seed beater, was introduced to intensify the harvest of seeds beyond previous levels.7

The technology was ingenious in its simplicity and practicality. Compared to the constant change and complexity of modern technology, it seems stagnant. We will find, however, that significant changes occurred in technology, and these changes shaped where people lived and for how long, what they ate, and how their societies were organized.

MOBILITY AND SETTLEMENT

Many writers observe that a simple tool kit is appropriate to a mobile society; but much of the technology found in foraging societies was actually cached at key locations, creating a “built environment.” The lifestyle was a traveling one, but like the high mobility we often observe in modern America, the mobility of ancient foragers was not aimless. In fact, the degree of mobility found in different places over the millennia varied greatly. The tempo, or the elapsed time between each move, also varied. During most periods, travel in the mountains and the deserts of the ancient American West is best described as intermittent. Some stops lasted weeks and months. Others lasted only a few days. It all depended on the circumstances.

Mobility is an aspect of settlement patterns—where people lived, how long, and with how many other people. Settlement patterns may have been altered by the introduction of the ...

Índice

Estilos de citas para Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau

APA 6 Citation

Simms, S. (2016). Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1568522/ancient-peoples-of-the-great-basin-and-colorado-plateau-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

Simms, Steven. (2016) 2016. Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1568522/ancient-peoples-of-the-great-basin-and-colorado-plateau-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Simms, S. (2016) Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1568522/ancient-peoples-of-the-great-basin-and-colorado-plateau-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Simms, Steven. Ancient Peoples of the Great Basin and Colorado Plateau. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2016. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.