![]()

Chapter 1

Russian Civil-Military Relations in Transition

The question of whether or not the military in Russia (1996-2001) took civilian authority to heart, following orders and transforming itself into an armed force consistent with political aims defined by civilians in control, is the central question of this book. In practice, there are many shades of gray in the realm of loyalty and subordination. Traditional theorists concerned with civil-military relations have identified a number of ways to gauge the dynamics of civilian control. Samuel P. Huntington and Morris Janowitz identified ways of assessing civilian control of the military based on the ethics of professionalism. Simply stated, they concluded that military forces would remain loyal and subservient to civilian control primarily because they would be educated according to what was the “right thing to do.”

This book rejects the application of traditional civil-military relations theories in contexts that might aptly be called transitions from authoritarianism. Widely regarded as the “deans” of civil-military relations theory, Huntington and Janowitz relied to a large extent on assumptions related to military professional ethics, a specific ethos that would predict certain outcomes in most cases. In post-Communist contexts these assumptions appear to be misunderstood, perhaps even inappropriate. Instead, taking a cue from Dale Herspring’s work on civil-military relations in post-Soviet Russia, this book proposes to answer the question of whether civilians were in control of the military in Russia from 1996 to 2001 by testing newer civil-military relations models in three cases. This time period is particularly useful because it represents the transition between Yeltsin and Putin. It may also aid in predicting future dynamics of civil-military relations in Russia, especially in the post-Putin era, if that is really what exists today. The security documents that derived from the transition between Yeltsin and Putin remain in force today, unrevised as of this writing, despite persistent rumors that a new military doctrine is in the works.

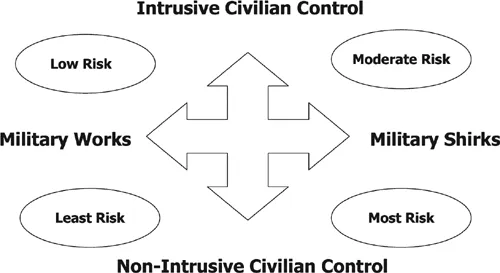

In a related question, the book also examines the extent to which infiltration of the military by security services (FSB, formerly KGB) impacts on military responses to civilian control. Peter Feaver’s “principal-agent” theory is based on his assumption that “the essence of civil-military relations is a strategic interaction between civilian principals and military agents.”1 Influenced by the degree and nature of civilian monitoring, as well as by their own value system, the military acts in varying degrees to fulfill (work) or undermine (shirk) civilian goals. The term “shirking” in this sense does not imply laziness or treachery, but describes a condition of less than full acceptance and cooperation that sometimes occurs between military agents and their civilian principals.

Figure 1.1 Principal-Agent Relationship

Although the Russian military may be likely to “shirk” no matter what civilians do, it may do so less openly (or overtly) if civilian monitoring is intrusive; if non-intrusive, the military may be inclined to shirk more obviously, in some cases even challenging, or undermining, civilian authority. Military behavior (working or shirking) causes civilians to vary the degree of monitoring (more or less). Thus, civilian control of the military both causes, and is caused by, correspondent military behavior.

Doctrine is one measure of civilian control of the military and is a primary focus of this book. Intrusive monitoring occurs when civilians assume the primary role in developing military doctrine. Non-intrusive monitoring occurs when the military is given or takes primary responsibility. Intrusive monitoring will include specific mission requirements and definitions related to actual performance, force structures, budgets and personnel policies. Non-intrusive monitoring is inadequately specific with regard to the same measures of effectiveness.

The major question for the principal is the extent to which he will monitor the agent. The decision centers on the degree of intrusiveness that is acceptable to both sides in the process of monitoring. Feaver suggests that it depends on the cost: The higher the cost, the less intrusive the monitoring is likely to be. The agent’s incentives are affected by the likelihood that his shirking will be detected by the principal and that he will then be punished for it: the less intrusive the monitoring, the less likely it is that the agent’s shirking will be detected. Feaver acknowledges the unsuitability of the term “shirking” when describing the action of the military agent when it pursues its own preferences rather than those of the civilian principal. The phenomenon is no less harmful in the military than it is among civilians. The most obvious form of military shirking is disobedience, but it also includes foot-dragging, leaks to the press, or pleas to the Congress, all designed to undercut civilian policy or individual policy makers. 2

In this book, civilian control is measured by tracing national security policy and military doctrine. Actual performance, force structure, budgets, and personnel policies are dependent upon military doctrine. The question of how national security strategy evolves into policy and doctrine is thus measured against actual performance.

Several different versions of national security policy and military doctrine were developed and implemented in Russia during the 1990s. In some cases, a number of different drafts were exchanged between civilian authorities (such as between members of the Duma Defense Committee and senior military officers) in an effort to “negotiate” requirements, roles and responsibilities. Several iterations among these drafts (in fact, most) were vague and unclear about military roles and responsibilities. What had been Yeltsin’s problems eventually became opportunities for Putin’s solutions as these documents transformed the civil-military relations dynamic.

Taken as evidence of civilian monitoring, doctrine establishes the norms of military behavior by addressing requirements and expectations, in terms of operational performance in battle, or in force structure, budgets, and personnel policies. Poor military performance in the first war in Chechnya during a period that was defined by vague and non-specific military doctrine, for example, supports a conclusion that the military was shirking under circumstances of non-intrusive civilian monitoring.

This book examines three cases in light of the dynamic relationship between policy and doctrine and performance, force structure, budgets, and personnel policies, outcomes that are caused by normative responses to doctrinal requirements. An example is the Kursk submarine tragedy in August 2000. In this case, policy and doctrine had already evolved considerably since the early 1990s. The documents in force at the time of the Kursk disaster much more closely related military doctrine to national security policy than previously. Still, in critical areas such as service-specific roles and responsibilities, links between force structure requirements and funding or personnel policies were all vague and sometimes even contradictory.

The situation for the navy was particularly acute during the period leading up to the submarine Kursk disaster. Because the 1993 military doctrine simply did not address maritime requirements, the sea service was left to define its mission by means of its own doctrine, distinct and separate from the nation’s military doctrine. This naval doctrine, entitled “World Oceans Concept” was endorsed by the Security Council and the Duma, then signed by the President in 1997. In it, the navy was charged with a requirement to be ready to defend Russia’s interests along its borders and on the “world’s oceans.”

Even the new military doctrine developed in 1999 and signed into law in 2000 still did not address service specific issues. Although the navy is used in this book to examine evidence of shirking in response to civilian monitoring, it was not alone in its dilemma. In Russia during the 1990s, and into 2000-2001, the armed forces were left to figure out on their own how they might best achieve the objectives set forth in the nation’s security policy and further specified in military doctrine. Reforms under Yeltsin, and later Putin, were not sufficiently specific to redress the shortfalls that led to incidents such as the Kursk disaster.

Conclusions based on these cases are, of course, highly subjective and vulnerable to speculation. However, by interpreting these cases, outcomes and conclusions help to determine the significance and potential application of newer civil-military relations theories in post-Communist contexts.

Information for this book was obtained by examining documents and published accounts based on memoirs, in both English and Russian languages, and by consulting notes from interviews with people who were present as participants in these events. Sources for this research include relevant western literature offered as an extensive annotated bibliography of references dealing with civil-military relations. Most importantly, evidence is based upon primary materials in the Russian language, including memoirs by key figures who were present and involved in political-military affairs in Russia during the period from 1996-2001 (Korzhakov, Akhromeyev, Shaposhnikov, and Grachev, for example), military journals such as Voenaya Mysl, Morskoiy Sbornik, press articles from Krasnaya Zvyezda, Nezavisimaya Gazeta, Argumenty i fakty, and Komsomolskaya Pravda, and official military documents, including published versions of doctrine, as well as some previously undisclosed drafts.

Evidence regarding national security policy and military doctrine was obtained as far as possible by examining official documents in the original Russian language and in the form of English language translations verified by the author. These source documents have been appended for ease of reference. Military performance, though not always apparent, can be measured to a certain extent by military journals and by documents that are readily available in the public record. Military matters of record in support of this research were obtained in a variety of ways. First, articles in military journals published in the Russian language that were written by senior military commanders about matters related to military affairs and battle readiness have been used extensively for the three primary cases that are part of this book.

Finally, the author’s personal and professional experiences during three years at the American Embassy in Moscow as U.S. Naval Attaché (1998-2001) offer a richly diverse and valuable resource. Interviews and discussions with Russian military and civilian authorities including General Anatoliy Kvashnin, (then) Chief of the General Staff; Admiral Vladimir Kuroyedov, (then) Chief of the Navy; General (retired) Makhmut Gareyev, of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and long associated with military thinking and development of doctrinal work; General Colonel Leonid Ivashov, (then) Head of the International Relations Directorate of the Ministry of Defense; General Colonel (reserves) Victor Ivanovich Yesin, (then) Chief of the Security Council Directorate of Military Structure and Organizational Development; Dr. Sergei Rogov, Director of the Russian Academy of Sciences Institute for Canada and USA Studies; Alexei Arbatov (then) Deputy Chairman of the Duma Defense Committee; and well known political-military journalists such as Alexander Golts, Pavel Felgenhauer, and others.

Exploiting an opportunity to fill a void in what is known about how civil-military relations models work in post-Communist systems this book breaks new ground. Civilian authorities sometimes behave insincerely in their dealings with the military, enhancing themselves or their positions by virtue of gaining the upper hand. For its part, the military may have motives that are less than noble, especially in view of the perquisites that are often associated with senior military positions. In an effort to generate greater support for the military point of view, senior officers may work to undermine civilian authority by foot-dragging, or shirking their duties. While unpalatable to the military culture of professional ethos, this phenomenon, if accurate, may be critical in understanding the peculiarities of civil-military relations in post-Communist political systems.

As the future unfolds Russia remains a puzzle in many ways, not least in how national security policy and military doctrine will evolve. As President Medvedev implements what may be a new and different era, it is important to consider how civil-military relations have evolved in the recent past. There is no other way to gauge transformation than by examining the basis from which it evolves.

Civil-Military Relations in Transition

The Cold War ended in 1989 in Germany when the Berlin Wall fell on 9 November. Two years later the Soviet Union collapsed, and the hammer and sickle flying atop the Kremlin walls in Moscow was replaced with the tricolor of the Russian Federation on 25 December 1991. The challenges of transition from communism to democracy are truly enormous, and have been researched in the context of a number of cases in Eastern Europe and former Soviet states. These challenges would have been daunting tasks even for a robust and invigorated system. But for Russia in the 1990s, many of the obstacles to democratization were so great that there was doubt whether or not the task was achievable.

Absent practical evidence of any of the critical institutions of government that are common to liberal democracies, Russia had neither a market-based private-property economy, a polity that was internally and externally sovereign, citizens’ judicial rights, nor representative government. As if this were not enough, Russia was also faced with the question of how to shape civil-military relations to secure democratic control of its vast armed forces, or, at the very least, to obtain the acquiescence of the military to democratic transition.

It is essential to understand what is meant by the term “military” in the context of this book. For this research, military is taken to mean the armed forces in uniform serving in military positions. Specifically, the term military means professional military officers, in particular those in authority as three or four-star rank who interface with senior civilian officials. The position of chief of the general staff is undisputedly a military position. Occupied by a uniformed member of the armed forces, this person is recognized as the leading authority on the military side of the civil-military relations equation. The minister of defense is not a military position. Rather, it is a position that is central to the legitimate authority of civilians over the military. When this position is occupied by a uniformed member of the armed forces the result can be confusion, undermining the balance in civil-military relations. In this case, perceptions of authority can be difficult to understand. When uniformed personnel occupy positions of authority that are, or normatively should be, associated with civilians, it can be hard to tell who is calling the shots.

In August 1991, the military was complicit in a coup attempt that, although ultimately unsuccessful, did briefly wrest power from legitimate authorities and place it into the hands of the coup-plotters. Yazov, as a uniformed defense minister, was complicit in the coup, while many in the military, Gromov, Lebed, Shaposhnikov, and Grachev, argued the opposite and managed to keep the “military” out of the operation. What it might take to precipitate a similar reaction in the longer term approaches to democratic transition was a question that brought civil-military relations in post-Soviet Russia sharply into focus during the 1990s.

There were other reasons to be less than optimistic about the prospects for securing civilian control over the military in Russia. In the Soviet era, the military was an integral component of the ruling elite. Just as communist ideology blurred the lines of distinction between the state and the individual, so it was between the soldier and the state. Under communist rule, the military’s loyalty was guaranteed by a three-fold effort: penetration of the military by the Communist Party, political education, and the provision of substantial resources to support the needs and requirements of the armed forces. Although the Communist Party no longer existed (at least not in its traditional form), its presence continued to be felt at all levels of the military for a long time.

The party’s mechanisms for monitoring military loyalty took different forms and transferred to other elements, but remained influential. Political education fell away, at least in a formal sense, as an element of training, but the sources of military doctrine still showed evidence of political influence long after the training had stopped. Finally, although the massive force structures that helped to make the Soviet Union a superpower had begun to diminish and decay long before the demise of the Soviet State, the military still possessed considerable infrastructure and means to implement national security strategy.

In the broader context of political, economic and social transition, the challenges of reforming civilian relations with the military had to be conducted against a backdrop of both domestic and international instability. Anxiety about possible military intervention in domestic politics, ostensibly to “protect the achievements of socialism,” “maintain domestic order,” “secure national interests,” or to defend the military’s own interests (institutional or economic) was based on very reasonable assumptions about how the military might react to efforts aimed at asserting civilian control. Civil-military relations thus became one measure of Russia’s commitment to democratization.

During communist times, civil-military relations were marked by civilian efforts to ensure military loyalty to the system’s values and institutions. As was the case for every branch of the state, the militar...