eBook - ePub

Dinosaurs and Dioramas

Creating Natural History Exhibitions

Sarah J Chicone, Richard A Kissel

This is a test

- 159 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Dinosaurs and Dioramas

Creating Natural History Exhibitions

Sarah J Chicone, Richard A Kissel

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Two experienced exhibit designers lead you through the complex process of design and installation of natural history exhibitions. The authors introduce the history and function of natural history museums and their importance in teaching visitors the basic principles of science. The book then offers you practical tricks and tips of the trade, to allow museums, aquaria, and zoos—large or small—to tell the story of nature and science. From overall concept to design, construction, and evaluation, the book carries you through the process step-by-step, with emphasis on the importance of collaboration and teamwork for a successful installation. A crucial addition to the bookshelf of anyone involved in exhibit design or natural history museums.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Dinosaurs and Dioramas un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Dinosaurs and Dioramas de Sarah J Chicone, Richard A Kissel en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sciences sociales y Archéologie. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Science Sets the Stage

Chapter One

A Brief History of Natural History Museums

"Nature is so powerful, so strong. Capturing its essence is not easy..."

—Annie Leibovitz

Natural history collections are the foundation for our understanding of the natural world. Whether it's a massive skeleton of an Apatosaurus or the delicate carvings of the Rosetta Stone, the objects of natural history inspire wonder and awe, and they provide humanity with a sense of place within our world. The human species is embedded in nature; we share in the "history of all natural living beings" (Cuvier 1797 in Taquet 2007, 4), and the role of natural history museums is to present that story to all. As gateways to inspiration and knowledge, museum exhibitions are critical to society's advancement and perception of itself. For this reason, exhibition developers and designers are both communicators and teachers; their influence is farreaching and they shoulder tremendous responsibility as a result.

This text is intended to help you navigate the design and development of natural history exhibitions; it offers a consideration of scientific process, visitor experience, and practical tricks and tips of the trade. This is a pragmatic guide tied specifically to those institutions dedicated to telling the story of nature and the science by which we know it—from aquaria and zoos to nature centers and natural history museums. We begin our journey by placing these venerable institutions in historical context.

From Private Collections to Public Institutions: Asserting Control over the Natural World

During the Middle Ages, there was little interest in natural history; collections did exist but were confined to wealthy abbeys and cloisters (Hagen 2008). The European Renaissance, or "re-birth," followed, set in motion by scholars and artists who traced their roots to the classical world. This movement represented an intellectual attempt to align with ancient wisdom and tradition, essentially relocating learning to the grove of the muses—the nine goddesses of poetry, music, and the liberal arts (Findlen 2003). With an influx of new specimens and artifacts, 1 preservation techniques, exploration, and religious reformation, there was a need to explain and order an increasingly illogical and pluralistic world, and a need to collect and arrange knowledge in an attempt to control it. The museum, rooted in scholarship, was—as some suggest—the "most complete response to the crisis of knowledge provoked by the expansion of the natural world through the voyage of discovery and exploration..." (ibid., 36). As collections continued to grow, the sheer number of things increased the need and desire to find order among them.

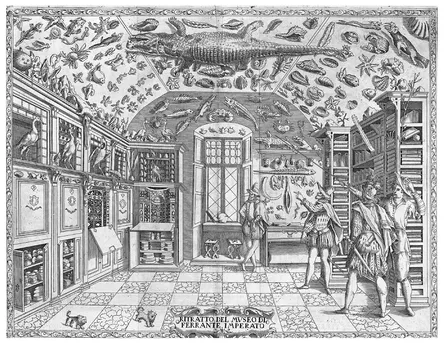

Our story begins, as many anthologies of natural history do, with the ubiquitous cabinets of curiosity known as Kunst- und Wunderkatmmers, studiolos, gallerias, or museos (Koeppe 2002). These were rooms (kammer) of art (kunst) and marvels (wunder), literally cabinets of "remarkable" things that, when taken together, reflected the authors' view of the world. They were "encyclopedic collections of all kinds of objects of dissimilar origin and diverse materials on a universal scale" (ibid., para 1)—collections of natural and artificial objects intended to represent the world in miniature (Fig. 1.1). Especially popular among the wealthy merchants and nobility of Europe, these early analogs often straddled the public and private divide (Findlen 2003). Some were kept under lock and key, closed sanctuaries for their owners—like Francesco I de'Medici's sixteenth-century studiolo in Florence's Palazzo Vecchio, a private collection and microcosm of his understanding and command of the world (Kinch 2011). Others were displays of wealth and self-aggrandizement, showcases for other prosperous and landed nobility—like Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II's Kunstkammer at the Hradschin Palace in Prague (Evans 1973). These collections of art, nature, and human engineering—large and small, shared or private—represent the precursor of the modern natural history museum.

An Affair to Remember: Science and Natural History

But how did these first cabinets of curiosity, with everything from "unicorn" horns to parades of shells, evolve into to the natural history museums of to-day—public institutions that promote scientific understanding and knowledge? The eighteenth century witnessed a number of significant milestones that impacted the development and institutionalization of natural history museums. As noted by Hoquet (2010, 31), '"natural history' was understood as the science of 'naturalia'—that is, the study of the three kingdoms of nature (mineral, vegetable, animal)." This broad and encompassing idea of natural history was based on Pliny the Elder's Historia naturalis (circa AD 77), which included 37 books that examined everything from beehives to the universe (Hoquet 2010). The 'universal history' of the Plinian model was reflected in leading eighteenth-century naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon's popular thirty six-volume Histoire naturelle, published between 1749 and 1789. Buffon's published work, along with his involvement in the transformation and expansion of the Jardin du Roi public garden in Paris (now the Jardin des Plantes), worked to define "natural history as a scientific enterprise" (Spary 2000,16).

Figure 1.1: An engraving of the collection of Ferrante Imperato—a Neapolitan apothecary—at the Palazzo Orsini di Gravina represents the earliest known pictorial representation of a natural history cabinet. Public domain, Wikimedia Commons,

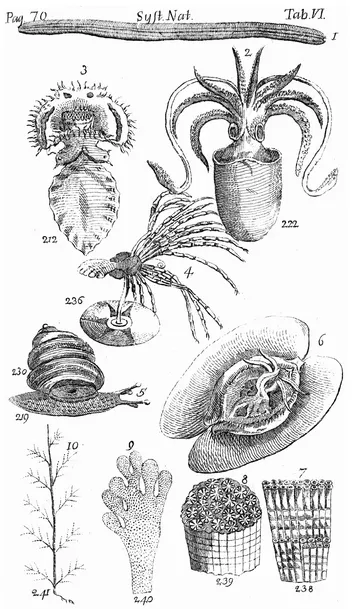

In addition to Buffon's contributions, Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician Carl Linnaeus' Systema Naturae (1735) and Species Plantarum (1753) had a direct impact on the ordering of knowledge. Prior to Linnaeus, there existed no consistent practice for scientifically naming species. Students of nature often used long, unwieldy Latin names, and many species received different names by different scientists, making both communication and any systematic organization of nature difficult. The wild briar rose, for example, had been named both Rosa sylvestris inodora seu canina ("odorless woodland dog rose") and Rosa sylvestris alba cum rubore, folio glabro ("pinkish white woodland rose with hairless leaves"). But throughout his works, Linnaeus developed the naming system still used today: binomial nomenclature. In this system, the names of species consist of two names, such as Tyrannosaurus rex or Homo sapiens, and species are classified within a hierarchical structure (Fig. 1.2).

FIGURE I.2. Image from Systema Naturae, highlighting invertebrate animals within Linnaeus' Classis Vermes. The tenth edition of his Systema Naturae, published in two volumes in 1758 and 1759 is considered the beginning of zoological nomenclature. Linnaeus' hierarchy classified living things within a simple, linear organization of most general (Imperium) to most similar (Varietas). This system evolved into that still used by many biologists today—a nested series of ranks: (Kingdom (Phylum (Class (Order (Family (Genus (Species))))))), though some recent authors have proposed yet another evolution of the system (e.g., de Queiroz and Gauthier 1992). Public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

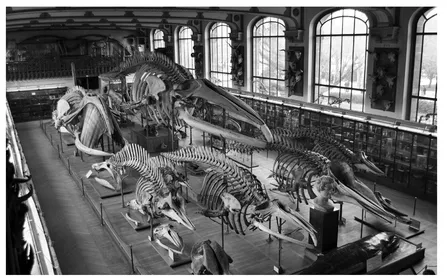

FIGURE I.3. Today, Cuvier's collections can be seen in the Galeries de Paléontologie et d'Anatomie comparée (Galleries of Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy), part of the French Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (National Museum of Natural History). Steren Giannini, Pannini, GFDL, Wikimedia Commons.

Linnaeus' work imposed order upon nature, and it was later described by Hagan (2008, 45) as the '"printed instructions' for the arrangement of a museum." As Hagan claimed, "The clear and logical mind of Linnaeus not only purified the system, but also enabled him to purge the collections of a considerable number of fabulous and fictitious objects..." (ibid., 45); indeed, much to the chagrin of the seven-year-old in all of us, this moment is when we lost the unicorn horns and the dragon's blood.

Despite their tenuous personal relationship and their differences in understandings of species and their classification2 (Sloan 1976; Conniff 2006, 2008), Buffon and Linnaeus, as well as other early advocates of natural history, had a significant impact on the way natural objects were conceived of and arranged—in relation to man (as in Buffon) or to each other (as in Linnaeus)—as well as the way relationships within the natural world were understood.

Early methods of classification were later expanded through the comparative anatomy studies of French anatomist Georges Cuvier's Cabinet d'anatomie comparée in Paris (Fig. 1.3). In 1802, when Cuvier became the Chair of Animal Anatomy at the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle—formerly BufFon's Cabinet d'Histoire naturelle in the Jardin du Roi—he began an aggressive expansion of the collections that lasted until his death in 1832. During his tenure the collection grew nearly 600 percent, from 2,898 preparations in 1802 to some 16,665 preparations in 1832 (Taquet 2007). This was a site of knowledge development and, ultimately, his museum "became the paradigm for museums around the world. They too wished to adopt a view of the museum as active experiment rather than passive representation" (ibid., 13).

A Triad of Purposes: Preservation, Research, and Education

It was this idea—that active scientific research should be located within the institution that also promoted the curation and display of collections—that saw museums and the object-based epistemology championed during the nineteenth century as central to the creation of disciplinary boundaries within the natural and social sciences, including archaeology, geology, paleontology, and biology (Conn 1998; Knell 2007). Conn (1998, 15) suggests that objects during the late Victorian age were seen as "the sites of meaning and knowledge," and, given that museums were the repositories of such objects, "many intellectuals regarded museums as a primary place where new knowledge about the world could be created and given order." Because scientific collections were expensive to collect and curate, beyond the reach of most liberal arts colleges and aspiring universities, "Natural history museums were the principal location for dialogues and the exchange of specimens among those debating the identification and connection among natural objects (and, later, human artifacts)" (Kohlstedt 1995, 151). Historians like Mary Winsor suggest that natural history museums, such as Louis Agassiz's Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University, were "scientific instruments, tools for investigation in the quest to understand living things" (ibid., 159).

An important aspect of museums as sites of knowledge creation was the subsequent availability of this knowledge to the "masses" in the form of exhibitions and programming; meaning was ultimately created and given form through the way objects were presented in displays (Conn 1998). Ichthyologist G. Brown Goode, Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution from 1887 to 1896, "publicized the central triad of purposes that marked urban museums at the end of the [19th] century—preservation, research, and education—and he developed a rationale for display that emphasized the importance of linking research ideas with the organized exhibitions of selected materials, including those of science and technology" (Kohlstedt 1995, 155).

The "Golden Age" of the American natural history museum, which reached its peak in the 1920s and 30s (Rader and Cain 2008), saw the popularization and institutionalization of classic natural history exhibitions. In 1927, Gladwyn Kingsley Nobel—head of the American Museum of Natural History's Department of Animal Behavior—insisted that "curators must...design exhibits that 'dissect and analyze Nature in such a way that the public will understand the principles controlling the life of the creatures portrayed'" (Nobel in Rader and Cain 2008, 157). The artistic efforts of Carl Akeley, noted for his realistic and taxidermal displays at the American Museum of Natural History, and artist Charles R. Knight (Fig 1.4) brought nature to life and popularized understandings of biological and anthropological development over time (Kohlstedt 1995, 160).

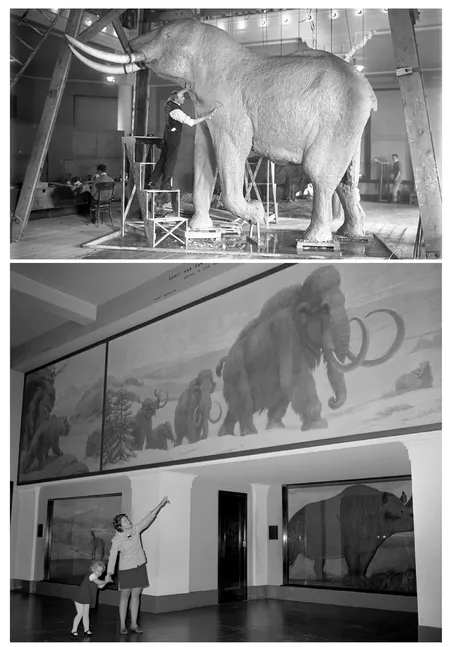

FIGURE I.4. Carl Akeley modeling an elephant in 1914 for the American Museum of Natural History's African Hall (top). In the 1920s, Charles R. Knight painted a series of 28 murals for the fossil halls of The Field Museum, bringing long-extinct beasts and more than two billion years of Earth's history to life; shown here are Knight's granddaughter Rhoda and her daughter Melissa admiring his mammoths and cave bear in 1969 (bottom). (top) Image # 34314 American Museum of Natural History Library; (bottom) © The Field Museum, #GN81615_2.

As attention continued to shift toward education during the 20th centu...

Índice

Estilos de citas para Dinosaurs and Dioramas

APA 6 Citation

Chicone, S., & Kissel, R. (2016). Dinosaurs and Dioramas (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1569243/dinosaurs-and-dioramas-creating-natural-history-exhibitions-pdf (Original work published 2016)

Chicago Citation

Chicone, Sarah, and Richard Kissel. (2016) 2016. Dinosaurs and Dioramas. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1569243/dinosaurs-and-dioramas-creating-natural-history-exhibitions-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Chicone, S. and Kissel, R. (2016) Dinosaurs and Dioramas. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1569243/dinosaurs-and-dioramas-creating-natural-history-exhibitions-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Chicone, Sarah, and Richard Kissel. Dinosaurs and Dioramas. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2016. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.