![]()

Chapter 1

Submerged Patriotism: Evolving Representation at the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial Visitor Center

History and memory shape perceptions of the landscape, and the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial is one such site where history and memory suffuse every aspect of the landscape. There is no escaping the emotional impact of standing on top of this sunken battleship, watching its slow leak of oil and realizing that this submerged ship is also a gravesite. Given the intensity of this landscape, the stories portrayed here take on additional weight, and the memories that are constructed during a visit to this site are particularly consequential in the construction of a U.S. national identity.

Figure 1.1 U.S.S. Arizona National Memorial (photograph by the author, 2005)

The location as well as the representation of iconic national historic events can have a deeply personal effect. Architectural historian Edwin Heathcote observes that "memorials to the dead co-exist with the wandering figures of the relatives and the curious; it is at once cathartic and the deepest engagements with the history."1 This deep engagement with a memorial and its representation can work rhetorically to "activate deep structures of belief that guide social interaction and civic judgment."2 This powerful mixture at the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial and its visitor center activates definitions of U.S. citizenship and patriotism within its representation of events surrounding the bombing of Pearl Harbor. The U.S.S. Arizona Memorial is an exceptional case study because its exhibits represent an explicit definition of U.S. citizenship, which includes specific acts that denote patriotism and nationalism.

The site's emotional wallop and its stimulation of civic judgment contribute to producing a historic site with many active and vocal stakeholders. The management and response to this large audience result in a perpetual tension concerning the development of its interpretive materials. An additional element in the creation of its visitor center concerned how to represent the U.S.S. Arizona within the vast World War II narrative. On account of the immense scope and consequential nature of these two matters in developing a new visitor center for the U.S.S. Arizona, the National Park Service staff began its planning in 2004 with the goal of a 2010 completion date.3 The previous visitor center was much smaller in narrative scope and in physical size; the vision for the new center was to be both larger and more inclusive of the World War II Pacific theater. The NPS established several goals for its new visitor center, which included—in addition to portraying the events of December 7, 1941—expanding the historical narrative of the U.S.S. Arizona, and making this site relevant to contemporary audiences.4 The U.S.S. Arizona Memorial personnel were rightly concerned that changes needed to take place in the interpretive materials in order for contemporary audiences to have a meaningful experience at the site. For the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial's interpretive materials to connect with contemporary visitors' lives, its long-established historical narratives needed to be revisited. The diverse publics that visit this site include those who are younger each year and have no personal connection to the site, as well as those visitors whose histories have never been included in the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial's narrative on-site.

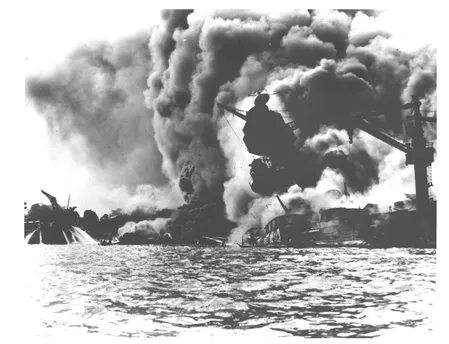

Figure 1.2 Iconic image of the bombing of the U.S.S. Arizona Battleship, December 7, 1941 (courtesy of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument Archives, Honolulu, HI)

Figure 1.3 Entrance sign to the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument (photograph by the author, 2011)

National and international historians continue to research and document historical experiences of those who have been underrepresented, misrepresented, or omitted from historical texts, and this is particularly relevant for World War II narratives. This chapter analyzes the controversy concerning the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial's 1980 orientation film and the objections of local audiences to its representation of Hawai'ians of Japanese descent as spies. Additionally, this chapter examines the changes between the 1980 and the 2010 visitor centers, the NPS response to the controversy, and whether the visitor center exhibits provide enough historical context to provide connections to their diverse publics' outside lives.

National commemorative and historic sites provide their audiences with an opportunity to reflect on events, and they provide a touchstone or basis for present and future actions for individuals and for countries. For many, the act of attending a national historic site is, in itself, a performance of citizenship and patriotism. The steady increase in historical tourism attests to its role in the performance of civic virtue, as well as the "worldwide upsurge in memory."5 In 2002, historian Pierre Nora observed that "every country, every social, ethnic or family group has undergone a profound change in the relationship it traditionally enjoyed with the past."6 With this upsurge, questions emerged regarding how civic virtue would be defined and how multiethnic histories would be incorporated into historical narratives. For memory studies scholars, these questions demand attention because the content as well as the form of these narratives contributes to producing messages that "stick" with visitors.7 That is, the construction of public memory and its "stickiness" or effectiveness depends on "particular audiences in particular situations."8

The changes that have taken place at the U.S.S. Arizona's visitor center offer insights into why and how this upsurge in memory contributed to revisions of their interpretive materials. The U.S.S. Arizona Memorial did include representations of its multiethnic population; however, its representation was a direct challenge to Japanese Americans' patriotism and nationalism. Local groups of Hawai'ians of Japanese descent argued for historical accuracy in a manner that both added complexity to the traditional historical narrative and "rehabilitat[ed] their past [which] is part and parcel of reaffirming their identity."9 The controversy regarding the depiction of Hawai'ian Japanese Americans at the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial raised a dimension of the visitor-centric exhibition shift that extended Robert Archibald's concerns with authenticity and core values. Archibald argues for the need to balance historical evidence and a site's core values in response to a public's demand for change in the interpretive materials.10 In this particular debate, both sides could demonstrate authenticity and an adherence to core values in the interpretive materials. To meet the demands of the Hawai'ian Japanese Americans, the traditional historical narrative for the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial had to be reimagined.

The National Park Service staff at the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial is acutely aware that visitors to their sites expect accuracy and elements of authenticity, as well as a narrative of the site's historic events. The controversy at this site concerned the accuracy and lingering racism in the Pearl Harbor attack narrative in the NPS's 1992 orientation film. Local groups were particularly upset with the film's implication that Hawai'ian Japanese Americans functioned as spies for Japan and demanded that the film be changed. To help readers to understand this controversy and its outcome, the next section examines the history of commemoration for the U.S.S. Arizona, the development of its first visitor center, the controversy over the NPS's orientation film, its resolution, and the development of the second visitor center. I conclude with a discussion of the lasting vicissitudes of the controversy in the 2010 visitor center and discuss how this case study can serve as an exemplar of diverse publics successfully engaging with a public history site in order to change traditional historiography to produce effective (sticky) historical narratives.

U.S.S. Arizona Memorial Background

Recently the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial was incorporated into a much larger monument by congressional proclamation. On December 5, 2008, Congress created the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument, with its official dedication on December 7, 2010. This site now includes nine historic sites representing various aspects of World War II history in the Pacific. In addition to the U.S.S. Arizona, the monument includes the U.S.S. Utah Memorial, the U.S.S. Oklahoma Memorial, four mooring quays that constituted part of battleship row, six chief petty officer bungalows on Ford Island, and three sites in Alaska's Aleutian Islands, which include the crash site of a consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber on Atka Island, the Kiska Island site of Japan's occupation that began in June 1942, and Attu Island, the site of the only land battle fought in North America during World War II. The last of the nine designations is the Tule Lake Segregation Center National Historic landmark and nearby Camp Tule Lake in California—both of which housed Japanese Americans relocated from the West Coast of the United States. The monument occupies a total of 6,295 acres, all of which are federal land.11 This analysis focuses on the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial, its visitor center, and the changes that have taken place at this public memory site. The planning and development for the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial's 2010 visitor center took place separately from the memorial's incorporation into the World War II Valor in the Pacific Monument.

The U.S.S. Arizona Memorial was dedicated on May 30, 1962. The architect was Alfred Preis, an Austrian American, who was living and working in Honolulu at the time and who had fled Nazi Germany in 1939. During World War II, he and his wife were interned for four months on Sand Island in Hawai'i as suspected enemy aliens.12 Also interned on Sand Island were "naturalized citizens, Italians, Germans, Norwegians, Swedes, Finns, and Hungarians. Next to them, separated by a twenty-foot fence, was the Japanese camp."13 The implementation of Japanese American internment was handled differently in Hawai'i than in the U.S. mainland, and this situation was due primarily to the large population of Hawai'ian Japanese Americans. "The number of Japanese in Hawai'i who were detained was small relative to the total Japanese population here: less than 1 percent.14 Preis's experience in the camp may have influenced his decision to create a hopeful design for the U.S.S. Arizona Memorial that included a tree of life. Even though initially the memorial was criticized for resembling a "squashed milk carton,"15 the memorial design went on to receive wide praise and has been described as "majestic" and as a "fitting shrine."16 Preis explained his meaning of the design as one that "sags in the center but stands strong and vigorous at the ends, [which] expresses initial defeat and ultimate victory."17 The memorial was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

Several forms of commemoration for the U.S.S. Arizona battleship had begun soon after the attack, one of which included military personnel saluting as they passed the sunken ship off Ford Island. In 1946, when Tucker Gratz, naval officer and Chair of the Pacific War Memorial Commission, "placed a lei" over the shattered warship, where he "found the wilted remains of the lei he [had] placed the year before."18 In fact, wreath-laying over the sunken battleship became so popular, that in 1957 the Tuscaloosa News declared: "Wreaths from each of the forty-eight states will be placed aboard the bomb-gutted sunken battleship U.S.S. Arizona. . . . It will be the first time in the sixteen years since the Japanese sneak attack that representatives from all forty-eight states have participated in such a ceremony."19

Figure 1.4 Lei floating above U.S.S. Arizona, May 30, 1962 (courtesy of the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument Archives, Honolulu, HI)

In 1950, the Navy erected a temporary wooden platform with a flag20 over the ship, and this platform is currently in storage on Ford Island.21 Subsequently, the Navy constructed the first permanent memorial in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1955, which consisted of a ten-feet-high basalt stone with a dedication plaque that was placed over the mid-ship deckhouse on the battleship.22 Plans for a larger memorial began in 1956, but there were substantial difficulties in raising funds for its construction. Creative fundraising for the memorial included a performance by Elvis Presley; all the proceeds went to the memorial's construction in 1961.23 Initially, plans for this memorial were under the auspices of the Pacific War Memorial Commission, the group that oversaw the development and construction of war memorials throughout the area.24 Concurrently, the Navy operated the site in order to preserve its control over the battleship's commemoration....