Saving Places that Matter

A Citizen's Guide to the National Historic Preservation Act

Thomas F King

- 240 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

Saving Places that Matter

A Citizen's Guide to the National Historic Preservation Act

Thomas F King

Información del libro

They're going to tear down the most cherished building in your town for another strip mall. How do you stop it? Tom King, renowned expert on the heritage preservation process, explains to preservationists and other community activists the ins and outs of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act—the major federal law designed to protect historic places—and how it can be used to protect special places in your community. King will show you the scope of the law, how it is often misinterpreted or ignored by government agencies and developers, and how to use its provisions to force other to pay attention to your concerns. He explains the quirky role of the National Register and the importance of consultation in getting what you want. King provides you with numerous examples of how communities have used the Section 106 process to stop wanton development, and encourages you to do the same. King's guide will be the bible for any heritage preservation or community activist movement.

Preguntas frecuentes

Información

Chapter One

Saving Places

Saving Your Place

Consider Section 106

- ▣ What does it mean for a place to be a "historic property" in the U.S.?

- ▣ How can you get your special place considered such a property?

- ▣ What does Section 106 require federal agencies to do?

- ▣ What does it require of other people?

- ▣ How can you use Section 106 to advance your interest in saving a place?

- ▣ What tricks do agencies and project proponents use to short-circuit or thwart the Section 106 process?

- ▣ What are some strategies for thwarting them?

Other Laws

Some Success Stories

- The Forest Glen Seminary is a collection of strange and wonderful old buildings that make Forest Glen, Maryland, unlike anyplace else in the world. The U.S. Army acquired the seminary before World War II but then neglected it. The buildings were falling apart when local residents, organized as "Save Our Seminary' (SOS), stepped in. Using Section 106 and other legal tools, and with help from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, they prevailed on the Army to do some interim preservation, but more importantly to move out altogether and let the seminary pass to the National Park Service. In partnership with the community and private developers, the Park Service is now overseeing its preservation, rehabilitation, and mixed-use redevelopment.

See: http://www.saveourseminary.org/News%2ofolder/what_is_the _nationgl_park_semina.htm for information.

See: http://www.saveourseminary.org/News%2ofolder/what_is_the _nationgl_park_semina.htm for information.

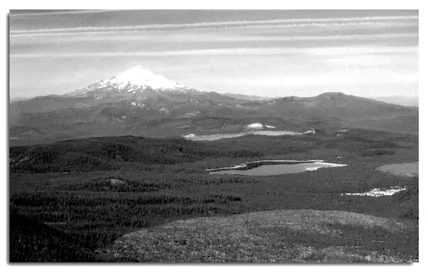

- The Medicine Lake Highlands are the remains of a gigantic collapsed volcano in northern California, mostly controlled by the U.S. Forest Service. Indian tribes of the area, notably the Pit River tribe, regard the highlands as an intensely spiritual landscape and have strongly opposed plans for geothermal energy production there. Using Section 106, the tribe and its allies were able to stop one drilling operation, but another was allowed to go forward. The tribe then took the involved federal agencies (Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management) to court and showed that their compliance with Section 106 and other laws was flawed; this halted the remaining project.

See: http://www.mountshastaecology.org.

See: http://www.mountshastaecology.org. - The Stillwater Bridge is an important part of Stillwater, Minnesota, an old mill town whose people value and have preserved its historic commercial core. When a new highway was built around Stillwater, the bridge technically became surplus, and because it crossed a designated scenic river, U.S. government policy demanded its demolition. Using Section 106, the people of Stillwater were able to negotiate successfully with the National Park Service, Federal Highway Administration, and Minnesota Department of Transportation, prevailing on them to retain and rehabilitate the bridge.

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stillwater_Bridge.

See: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stillwater_Bridge.

- Kahoolawe Island figures heavily in Native Hawaiian tradition and is loaded with ancestral Native Hawaiian residential, burial, and spiritual sites—but for many years it was used by the U.S. Navy for target practice. Using Section 106 and other laws, Native Hawaiians persuaded the Navy to move its bombardment exercises elsewhere and to clean up the unexploded ordnance on the island. The island is now controlled by the State of Hawaii and is visited regularly by Native Hawaiians to carry out ceremonial and cultural activities.

See: http://www.kahoolawe.org/.

See: http://www.kahoolawe.org/. - Hingham, Massachusetts is a well-preserved old town in Plymouth County, Massachusetts. The railr...