Chapter 1

Introduction

Jon Dowell

This book is about medication use and the prescribing process in the western context. Increasingly, patients want to participate in decisions about their care, and we consider how the ‘patient-centered’ approach can help this process. In particular, we focus on the difficulties that suboptimal medication use can create and how this issue (often labelled as non-compliance or non-adherence) can be approached within consultations using techniques based on this philosophy. This problem has vexed clinicians for generations, but the increasing trend towards partnership between patients and clinicians is shifting thinking and offering new approaches. In the UK, the term concordance has been coined to exemplify this shift but, to us, this simply represents the maturation of the principles and practice of truly patient-centered care into the therapeutic element of the consultation. Increasingly, it is not seen as sufficient for clinicians to explore patients’ perspectives in terms of feelings, ideas, function and expectations and then to direct them as to how to respond – for instance, what medication to take. Sharing decisions about treatment has always been present in the patient-centered clinical method, but the emergence of a literature on how this might be achieved reflects the increasing emphasis placed upon it (Brown et al., 1989). We argue here that there is enormous potential value in understanding this process and building the skills to implement it for two reasons. First, there is ample evidence that medicines are used suboptimally throughout the world, and any means of improving this is worth exploring. Secondly, non-compliance commonly undermines the clinical relationship, sometimes including deliberate deceit and making rational advice or decisions impossible. Avoiding or overcoming this trap must be a worthwhile objective.

Just as gathering the biomedical details of a clinical history is based upon an understanding of the potential pathologies involved, it is also valuable to appreciate how patients’ beliefs, values and other influences can influence their eventual use of a treatment. In the same way that ideas or fears about a symptom can assist or prevent patients accepting a diagnosis, ideas or fears about medicines will affect their willingness to accept them. Appreciating the range and origins of different beliefs about medicines will enable clinicians to identify symptoms of problems and explore these further, just as they would for physical problems. This book is designed to provide an understanding of the types of problems that underlie ineffective medication use and some tools for opening up this topic with patients. This is not always easy, especially when deceit is involved, and this area is covered in some depth in Chapter 7.

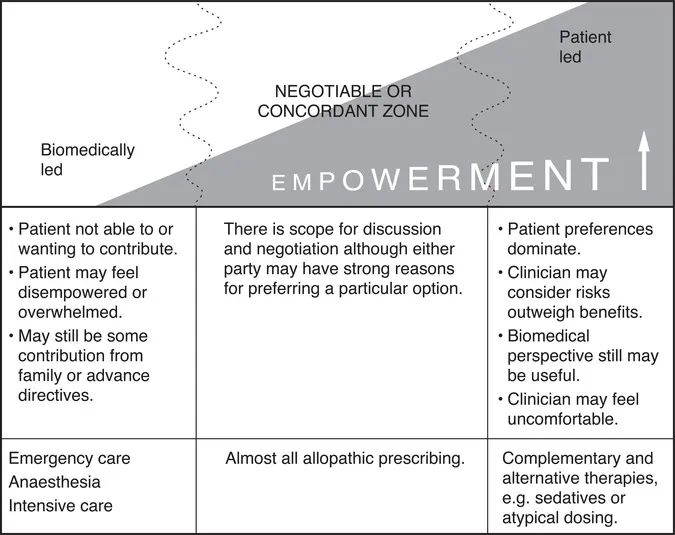

Conceptually it might be helpful at this point to introduce the notion of a spectrum of prescribing. Clearly there are times when patient involvement is not possible, helpful or appropriate to seek, emergency care being the prime example. However, even here patient autonomy is acknowledged through advance directives precluding blood transfusion for Jehovah’s Witnesses, for instance. At the other end of the spectrum are choices where the clinical evidence does not allow clear guidance or there may be genuine clinical ‘equipoise’ (Elwyn et al., 2000). An example of this might be the short-term use of hormone replacement for menopausal symptoms. Within this spectrum there is scope for increasingly empowering patients by involving them in decisions as they wish (Howie et al., 1997). There is also scope for the preferred style of the patient and the clinician to match or clash. Depending on the nature of the decision and the preferences of the individuals concerned, it might be more or less easy and, indeed, comfortable to achieve agreement. However, outside the hospital setting, patients obviously control their medication use and have the final say, so it beholds clinicians to gain their support. The question is how and what to do if they can’t.

A prescribing spectrum

Figure 1.1 A prescribing spectrum.

Prescribing in a patient-centered way is therefore an approach designed to foster mutual understanding and collaboration. It does not imply that all patients should receive whatever they want. Clinicians have responsibilities to wider society as well as professional and institutional rules within which they must operate. How these factors can be managed when they conflict with patient-centered care is described in Chapter 7.

As most prescribing occurs in the primary healthcare setting, we make no apologies for the fact that much of our evidence and supporting case studies originates from family practice. To date this principally reflects interactions between doctors and patients, but nurses and pharmacists in both hospital and family practice are playing an increasing role in the prescribing process. Consequently, this book is aimed at all professionals involved in the process of helping patients to consider and use pharmaceutical products. We use the generic term ‘clinician’ throughout to include anyone playing this role in a pharmacy, family practice or hospital setting, and in Chapter 6 we discuss how different professionals can help patients to participate in the process even if they themselves do not prescribe.

The book is structured in two sections. The first section (Chapters 2, 3 and 4) considers what the literature tells us about medication use from the perspectives of the clinician, the patient and behavioral sciences, respectively. This more academic perspective is illustrated with numerous patients’ stories and quotes, especially in Chapter 4, and is designed to provide the understanding required to interpret what patients are likely to say. The second section (Chapter 5 onwards) is a more practically orientated ‘how to’ guide, and for hasty clinicians who wish to skip the background material we would recommend Chapter 5 as the start of the more applied techniques for exploring individual patients’ medication use and intervening in a patient-centered manner.

Chapter 2 commences by discussing the volume of medicines prescribed and some of the problems that appear to result from patients’ responses, before exploring these issues from the medical perspective. We then move on to consider how medicines fit into patients’ lives more broadly, how their views affect their decisions about medicines, and what this implies for the prescribing process. In Chapter 4, using research material from our own projects and from the available literature, we shall explore how various psychosocial models might help to explain medicine-taking behaviors and the implication of this for practice.

The second section of the book is aimed specifically at those with responsibility for prescribing. We present a potentially more manageable single model of the relevant factors developed through research based on both patients’ experiences of receiving medicines and doctors’ experiences of prescribing in a number of settings. By presenting patients’ stories we hope to help clinicians to see how they can access patients’ thinking about both illness and treatment. This is extended in Chapter 6 by considering how to develop more patient-centered approaches to the process of prescribing, under what we might term ‘normal’ conditions of clinical practice. It also considers how other professionals can assist or disrupt this process. Chapter 7 introduces techniques that have been devised from patient-centered principles to use when non-compliance is thought to be likely. Again, examples are given to illustrate the process. Chapter 8 presents some of the unresolved issues and highlights the difficult issues that can arise – for instance, when patient choice clashes with evidence-based approaches. The final chapter contains a synopsis of patient-centered prescribing, discusses some areas that merit further research and presents ideas about how you may seek to develop these skills if you wish to.

By the end of this book we hope that you, the reader, will have a good understanding of the current issues with regard to the prescribing process and medicine-taking behaviors. You should also be in a position to experiment with new approaches to prescribing medicines, based on a richer understanding of patients’ thoughts, feelings and behaviors. You might do this in the hope of at least diffusing potentially difficult clinical relationships and sometimes significantly improving suboptimal patient care. And here, immediately, we strike upon one of the key issues for this whole concept. Is the goal always to improve what clinicians see as suboptimal care? Surely this is true when it accords with the patient’s priorities, but what if it might not do so? Even assuming that we have overcome the difficulties of sharing information and can be confident that a decision is truly informed, when do a patient’s values override clinical practice or protocols? Throughout this text, as we weave a course between patient autonomy and clinicians’ responsibility, this line becomes as blurred as it is in practice. But, as authors, our stance is clear – it is the clinician’s role to advise to the best of their abilities but not to dictate what patients should do unless they are explicitly invited to do so.

Definitions

The language surrounding medication use is often a sensitive matter, and it can obscure the issues if not handled consistently. It might therefore be helpful to clarify the way we have sought to address this problem and to indicate how we have chosen to use selected words. Although many readers will be very conscious of a preference for the term adherence over recent years, we have elected to use compliance throughout the text precisely because it highlights the paternalistic nature of the underlying assumptions that this concept reflects. This is not because we support the term, but rather because we want to highlight the incongruence of the concept unambiguously. Adhering to advice, even voluntarily, does not seem to be sufficiently distinct from complying with an instruction. Neither requires the patient to participate in or share the decisions that are made.

In order to provide a more considered approach, we clarify here how we are using these terms.

Compliance/adherence

This is the extent to which medication use follows the prescriber’s instruction. This may be ideal, over or under that recommended, or vary in other ways such as timing, frequency of dosage or route of administration.

Compliant/adherent

This term describes a pattern of medication use that matches the prescriber’s instruction. The extent to which use and instruction correspond may vary, but the acceptable level is determined by the clinician.

Concordance/patient-centered prescribing

Here there is agreement between the patient and the prescriber that a treatment is an effective way of achieving the patient’s goals. It is characterized by an exchange of views designed to mutually inform each other, and a process of establishing a sufficiently shared decision. Agreement may be easy, may require negotiation or may possibly be agreement to differ, in which case the beliefs and wishes of the patient take priority. Discordance is not a judgemental term, as it does not favour either view. Hence non-concordance is a misnomer and is not in any way a synonym for non-compliance.

Discrepant medication use

This term is suggested to describe patterns of medication use that do not match those intended by the patient – for instance, due to low motivation or perhaps memory problems.