The due and equably warming of rooms in cold climates, it must be admitted, is of great importance to the health and comfort of the inhabitants of every dwelling, from the cottage of the servant to the palace of the sovereign. So necessary is warmth to existence that we cannot be surprised at the various inventions that have been produced for the better and more economical warming of our houses.

The architect will do well to examine and reflect on the different modes adopted by painters of introducing light into their studios. The ‘lumière mystérieuse’ so successfully practised by the French artists is a most powerful agent in the hands of a man of genius, and its power cannot be too fully understood, not too highly appreciated. It is, however, little attended to in our architecture, and for this obvious reason, that we do not sufficiently feel the importance of character in our buildings, to which the mode of admitting light contributes in no small degree.

Sir John Soane (1753–1837) made these statements in Lecture VIII of the series that he delivered, between 1810 and 1820, in his capacity as Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts.9 This is the lecture in which he most directly addressed aspects of the environment in buildings. ‘Warming’, a more felicitous term than our modern reference to ‘heating’, is identified quite pragmatically as an element of ‘health’ and ‘comfort’, whereas light, although of practical value, is considered to be an ‘agent’ of ‘character’ in architecture. While the statements maintain separation between the thermal and the luminous environments and seem to distinguish between the quantitative – warming – and the qualitative – lighting – it may be argued that in the realisation of his buildings Soane brought together all of the dimensions of environment into a complex synthesis.

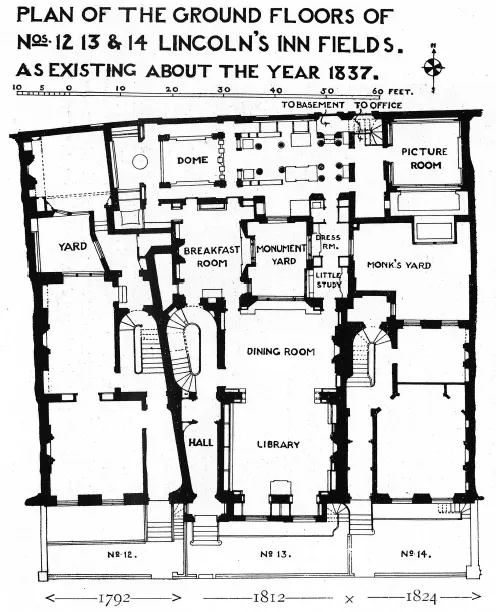

Soane first occupied a part of the premises on the north side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London (latitude 51° 30′ N) in 1792 and lived there up to his death in 1837. The process of reconstruction of the houses numbers 12, 13 and 14 continued for much of this period and is well documented.10 As the years passed and Soane took over yet more of the buildings it is possible to see how the arrangement in plan, particularly in the museum and office, became less cellular, more interconnected (Figure 1.1). This process also occurred in cross section as the rear yards were progressively covered over and vertical links established as the accommodation for the office and the museum took shape.

Figure 1.1Soane house and museum, 12–14 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London ground floor plan in 1837.

Willmert has shown the extent of Soane’s interest in innovations in methods of warming, as they are revealed by both the texts of the Royal Academy lectures and the contents of his library, in which there are no less than seventeen books and pamphlets on the subject.11 But even more authoritative than these documents is the evidence of his practical application of new systems of warming into designs for buildings from as early as the steam heating installation at Tyringham House that was completed in 1797. Experiments in heating were made in the works at the Bank of England and in many other projects. This direct experience of the design, installation and use of these devices, as Willmert attests, equipped Soane to apply them in the reconstruction of his own house.

In the forty five years that Soane lived at Lincoln’s Inn Fields he seems to have almost continuously experimented with all conceivable methods of heating, encompassing stoves, fireplaces and three kinds of central heating installation using, in turn, steam, warmed air and hot water as the heating medium.12 These were applied to the apartments at the northern edge of the house, behind the windowless façade facing the mews at Whetstone Park that contained Soane’s professional office and the museum that housed his ever-expanding collection of works of art. In contrast the heating arrangements of the main body of the house were relatively conventional, retaining the tradition of the open hearth as the principal, usually the sole, source of heat. In explanation, Willmert cites Soane declaring that in their houses the English must, ‘see the fire, or no degree of heat will satisfy’.13

The realisation of effective heating in the museum took Soane many years and numerous false starts were made, but finally, in 1832, the installation of a hot water system by the engineer A. M. Perkins seems to have solved the problem. This is extensively described in Charles James Richardson’s, A Popular Treatise on the Warming and Ventilation of Buildings, first published in 1837.14 Richardson was an architect who worked in Soane’s office from 1824 and his book is devoted exclusively to the illustration of installations of Perkins’s system. With reference to Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Richardson wrote of, ‘The perfect success of Mr. Perkins’s system … especially as I well remembered the miserable cold experienced in the office during former periods’.15 The extent of the installation was described in full technical detail.

There are 1,200 feet of pipe in the Soane Museum. It is divided into two circulations; one of which warms the picture-room, and the two rooms beneath. The other, which has the largest circulation annexed to it, first warms the office in which the expansion and filling pipes are placed; the pipe then traverses the whole length of the Museum, then passes through the breakfast-room under the long skylight, intended to counteract the cooling effect of the glass; it then passes through the floor into the lower room, forms a coil of pipe of 100 feet in the staircase, and returns to the furnace, passing in its course twice round the lower part of the Museum; a coil from this circulation is likewise placed under the floor of the dressing-room, which, by an opening in the floor and the side of the box, admits a current of warm air into the room above.16

This was almost certainly one of the first instances in the history of architecture in which a complex and specialised spatial organisation was rendered thermally comfortable by an advance in technology. It anticipates by nearly a century Frank Lloyd Wright’s synthesis of heating with the open plans of the Prairie houses, as described by Reyner Banham.

Here, almost for the first time, was an architecture in which environmental technology was not called in as a desperate remedy, nor had it dictated the forms of the structure, but was finally and naturally subsumed into the normal working methods of the architect, and contributed to his freedom of design.17

By common assent Soane’s over-riding environmental concern was with the quality of the luminous environment of his buildings. As David Watkin shows,18 the ideas of Le Camus de Mézières, most particularly in relation to the effects of light, la lumière mystérieuse, lay at the centre of Soane’s architecture.19 The essential instruments in the realisation of these effects were the use of top-light, false or mysterious light and reflected light. John Summerson proposed that top-lighting, which Soane adopted as a matter of necessity in his work at the Bank of England, ‘becomes an essential of the style’ in the works of the so-called ‘Picturesque...