eBook - ePub

Animals in the Middle Ages

Nona C. Flores, Nora C. Flores

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 224 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Animals in the Middle Ages

Nona C. Flores, Nora C. Flores

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

These interdisciplinary essays focus on animals as symbols, ideas, or images in medieval art and literature.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Animals in the Middle Ages un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Animals in the Middle Ages de Nona C. Flores, Nora C. Flores en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Literature y Literary Criticism. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

MORE THAN AN ANIMAL

MOVABLE BEASTS

THE MANIFOLD IMPLICATIONS OF EARLY GERMANIC ANIMAL IMAGERY

![Figure 1. The Sutton Hoo helmet, front view. Detail, above: boar’s head eyebrows terminals. (After Bruce-Mitford, Sutton Hoo [n. 1 below], 35. The British Museum, London. This drawing first appeared as figure 7 in Glosecki, Shamanism and Old English Poetry [n. 6 below].)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1578134/images/fig1-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 1. The Sutton Hoo helmet, front view. Detail, above: boar’s head eyebrows terminals. (After Bruce-Mitford, Sutton Hoo [n. 1 below], 35. The British Museum, London. This drawing first appeared as figure 7 in Glosecki, Shamanism and Old English Poetry [n. 6 below].)

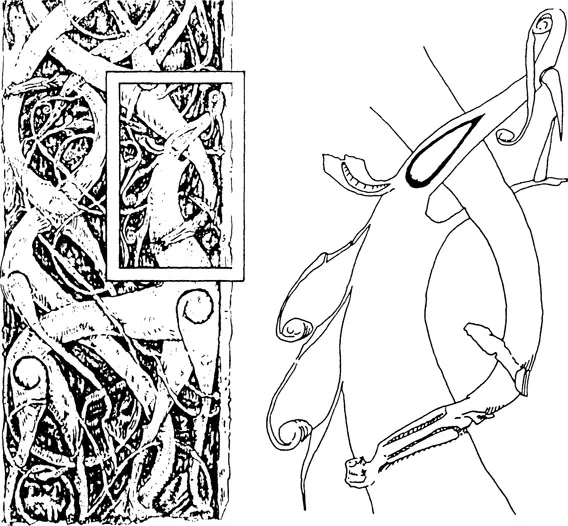

Early Germanic art—strange, fanciful, mysterious—tantalizes the mind with zoomorphic design. Graphic and literary sources alike confront us with convoluted images of energetic animals. Sometimes the media coalesce: boar figures on Beowulf’s helmet appear in precisely the same place, ofer hleorbergan “above the cheekguards,” as does the boar’s head on the Sutton Hoo helmet (see figure 1).1Similarly, architectural ornament looms up before us in these famous lines from the Old English Wanderer (97–98), which could be describing wall panels on the stave church at Urnes in the Sognefjord (see figure 2):

Stondeð nu on laste leofre duguþe

weal wundrum heah, wyrmlicum fah.2

[Stands now in the track of the troop we loved

a wall wondrous high writhing with snake-shapes.]

weal wundrum heah, wyrmlicum fah.2

[Stands now in the track of the troop we loved

a wall wondrous high writhing with snake-shapes.]

Serpentines on this high wall suggest the surface ornament so typical of Germanic art around the end of the first millennium, when stylized beasts explode into streamers of limbs, tendrils, and tangles that render the subject species unrecognizable and apparently inconsequential. Elsewhere, though, the species of beast is quite clear. Incised on stone, cast in bronze, filigreed in gold, cloisonnéed in garnet, embossed in repoussé, carved in oak, envisioned in elegy, invoked in epic, petrified in personal names—an entourage of the same animals unfolds before us—boar, bear, wolf, hart, horse, raven, eagle, serpent, fish—silent, fanciful, mysterious, sometimes with glittering garnet eyes that seem supercharged with secrets (see figure 3).

Returning the blank gaze of these obsolete icons, the height of human art in their day, we sense the symbolism of strength, many murky implications, including the notion that those who made such elaborate designs must have done so deliberately, in honor of ancient traditions. And yet there can be little doubt that as the centuries wore away, artist and artisan alike crafted these creatures almost automatically, as part of their patrimony. As the Migration Age interlace evolved through the so-called Style II of Sutton Hoo and on past Jellinge, Mammen, Ringerike toward its ultimate expression at Urnes,3 one artisan undoubtedly imitated another, who mimicked his master, who followed his father, who had just carried on unquestioningly with conventional motifs initiated by the ancestors. Maybe by the end of the first millennium any clear meaning had melted away from the expected images of the same old animals. If we could revive a Viking Age artisan (see the palms calloused from smooth-hafted steel chisels, the thumbnails blackened from silver and stinging sulphur inlaid as niello), if we could ask a Norse silver-, stone-, iron-, or tree-smith why the workmanship crawled with contorted creatures, then perhaps, like a Pennsylvania farmer posing beneath the hex sign on the barn, this revenant would respond jafn for fagr “just for pretty.”4

Thus, toward the end of the first millennium, as the graphic tradition followed the outmoded Germanic gods off into obscurity, when busy

![Figure 2. Urnes stave church, Sogn, Norway: carved portal panel. (After Walther Roggenkamp in Lindholm, Stave Churches [n. 5 below], pls. 26, 28.)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1578134/images/fig2-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 2. Urnes stave church, Sogn, Norway: carved portal panel. (After Walther Roggenkamp in Lindholm, Stave Churches [n. 5 below], pls. 26, 28.)

surface ornament seems to have become an end unto itself, perhaps there lingered in the minds of those who made it no clear concept of this animal art’s arcane origins. Imitation tarnishes inspiration. Maybe any mythic content had evaporated from the indeterminate quadruped all wrapped in snakes at Urnes, shown in figure 4. Perhaps by 1060 such sinuous beasts had become nothing more than wood shaped well to catch an idle eye.5

![Figure 3. Sutton Hoo purse-top plaque (Woden with wolf companions?) (“Man-between-monsters” motif, after Evans, Sutton Hoo Ship Burial [n. 1 below], pl. VIII. The British Museum, London. This drawing first appeared as figure 3 in Glosecki, “Men among Monsters” [n. 6 below]; subsequently it appeared as figure 17 in Glosecki, Shamanism.)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1578134/images/fig3-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 3. Sutton Hoo purse-top plaque (Woden with wolf companions?) (“Man-between-monsters” motif, after Evans, Sutton Hoo Ship Burial [n. 1 below], pl. VIII. The British Museum, London. This drawing first appeared as figure 3 in Glosecki, “Men among Monsters” [n. 6 below]; subsequently it appeared as figure 17 in Glosecki, Shamanism.)

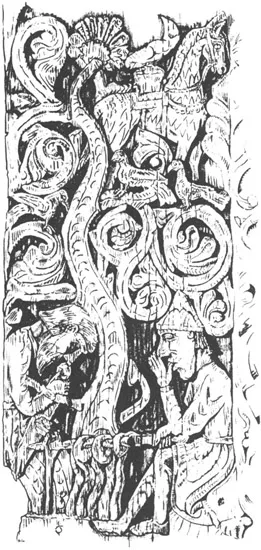

Yet such was not the case a century later, when carving on the Hylestad and Vegusdal churches delineated scenes that indisputably illustrate the Sigurð and Fáfnir story. For these woodsmiths, there was obviously meaning behind the medium. And for those who know the Volsunga cycle, the referent of a hero roasting a dragon heart by a sleeping smith beneath singing birds is immediately apparent: this warrior can be none other than the archetypal dragonslayer of Germanic myth, whether we call him Sigurð (ON), Sigemund (OE), or Siegfried (MHG).6 Patently, these pictures such as figure 5 are not efne for fæger, “just for pretty.” No, this anthropomorphic art preserves the beleaguered mythos of a proud people whose artists saw no sacrilege in adorning Christian churches with the exploits of heathen heroes. Thus the narrative panels from Hylestad—in which literature and representational art again coalesce, this time to give us graphic Heldensagen—have glaring mythic content, quite particular implications.

Figure. 4. Urnes carving, portal panel, detail. (After Roggenkamp in Lindholm, Stave Churches, pl. 29.)

Why should the situation be different for the recurrent animal motifs, even though—to us, at least—they seem so much less referential than the Hylestad illustrations? I suspect that at least in the earlier phases of this tradition, the more familiar beasts were equally referential. Although their mythic implications must have steadily eroded as the influence of Rome advanced, nonetheless these beasts originally conveyed socioreligious significance to those who made them and to those who admired them. As Foote and Wilson write, “There was apparently a need for art in everyday life.”7 And as I have argued elsewhere,8 this mysterious animal art that originated in the Iron Age and persisted through the Viking Age was only coincidentally aesthetic. Originally, the icons on weaponry were not at all “for pretty”: they were for protection from ethereal as well as corporeal adversaries. So the contemporary significance

Figure 5. Sigurð and Regin, carved portal panel, stave church at Hylestad, Norway. (After Roggenkamp in Lindholm, pl. 47. Universitets Oldsaksamling, Oslo.)

of much of this animal art was broadly mythic, narrowly apotropaic. Such art—boars and bears on armor; wolves, stags, steeds, eagles on royal regalia—was effective, not affective. It was meant to acknowledge and probably propitiate the inscrutable cosmic forces whose powers ordinary people found impossible to resist. Moreover, among quasi-tribal societies still dependent upon the hunt, the natural embodiment of these animistic impulses regularly takes the shape of significant beasts, whose image, according to the principles of sympathetic magic, equals the object represented. “Watch out for the wolf when you see a wolf’s ears!” (Fáfnismál, l. 35).

![Figure 6. The Benty Grange boar helmet. (After Bruce-Mitford, Aspects [n. 1 below], pl. 63. The Sheffield City Museum, West Park, Sheffield. This drawing first appeared as figure 6 in Glosecki, Shamanism.)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1578134/images/fig6-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 6. The Benty Grange boar helmet. (After Bruce-Mitford, Aspects [n. 1 below], pl. 63. The Sheffield City Museum, West Park, Sheffield. This drawing first appeared as figure 6 in Glosecki, Shamanism.)

This is just one of the more crucial implications of the early animal art. The apotropaic power of the battle emblem is most obvious in representations of a sacral beast that bulled its way into the center of my studies fifteen years ago and still refuses to budge:

Ac se hwita helm hafelan werede,

se þe meregrundas mengan scolde,

secan sundgebland since geweorðad,

befongen freawrasnum, swa hine fyrndagum

worhte wæpna smið, wundrum teode,

besette swinlicum, þæt hine syðþan no

brond ne beadomecas bitan ne meahton.(Beowulf, ll. 1448–54)

[But the glittering helmet guarded his head;

it had to stir up the sea floor,

enter ocean currents exalted with treasure,

fit round with lordly bands; far back in the old days

the weapon-smith wrought it thus, worked it with magic,

set it with swine shapes so that thereafter no

blade nor battle sword might bite through.]

se þe meregrundas mengan scolde,

secan sundgebland since geweorðad,

befongen freawrasnum, swa hine fyrndagum

worhte wæpna smið, wundrum teode,

besette swinlicum, þæt hine syðþan no

brond ne beadomecas bitan ne meahton.(Beowulf, ll. 1448–54)

[But the glittering helmet guarded his head;

it had to stir up the sea floor,

enter ocean currents exalted with treasure,

fit round with lordly bands; far back in the old days

the weapon-smith wrought it thus, worked it with magic,

set it with swine shapes so that thereafter no

blade nor battle sword might bite through.]

Manifold implications emanate from this central image. Most striking is the boar’s apotropaic power, the focal point of this passage. Whether we date Beowulf to the “age of Bede” or to the century before the Conquest, the epic in any case shows that the traditional associations remained accessible to this Anglo-Saxon poet long after their dim origin among the northern tribes described by Tacitus in 98 A.D.9 Noting their superstitious nature, the Roman historian writes that they considered the

![Figure 7. Detail, the Benty Grange helmet: boar crest. (After Webster and Backhouse, Making of England, [n. 3 below], pl. 46. The Sheffield City Museum, West Park, Sheffield.)](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1578134/images/fig7-plgo-compressed.webp)

Figure 7. Detail, the Benty Grange helmet: boar crest. (After Webster and Backhouse, Making of England, [n. 3 below], pl. 46. The Sheffield City Museum, West Park, Sheffield.)

boar’s effigy their best protection in battle (Germania, 45).10 So, for this animal image at least, the ancient implications lived on tenaciously, despite drastic changes in the culture that preserved boar figures in its art (see figure 6).

The preeminence of the boar reflects this animal’s importance as a food species in Iron Age Europe when, at 700 pounds, it snarled out of the brush to attack hunting parties, who thus knew the beast’s formidable strength firsthand. People with an animistic outlook—tribal people who invest their universe with endless busy spirits—tend to equate physical force with spirit power. Thus, still today a symbol of tenacity, the boar quite naturally becomes the particular guardian of the armed man ringed by enemies, fighting for his life in times that must have been still more terrible than epic and saga show.

This boar crest (see figure 7) is thus a “movable beast”: some of these talismans were literally removable, since Njáls saga says that, with hostility imminent, warriors put battle emblems on their helmets (ch. 142). Presumably, they removed these emblems after the fight, perhaps as a gesture of respect to the creature of power.

More importantly, though, the boar as an English symbol—a movable beast—survived cultural changes to reappear in a Middle English romance, where it retains an echo of its old value in the much earlier epic. It moved from one symbol system to another, its image fully intact, although its content shifted drastically. In Gawain and the Green Knight, where the boar’s symbolic association with the tempted hero is well known, we still see remnants of ritual in the procession following the second hunt, when the boar’s head is borne triumphantly back to Bercilak’s castle (ll. 1615–18):

Now with þis ilk swyn þay swengen to home;

Þe bores hed watz borne bifore þe burnes seluen

Þat him forferde in þe forþe þurg forse of his honde

so stronge.11

[Now with this same swine homeward they sway,

The boar’s head borne before the baron himself

Who killed it in the creek through craft of his hand

so strong.]

Þe bores hed watz borne bifore þe burnes seluen

Þat him forferde in þe forþe þurg forse of his honde

so stronge.11

[Now with this same swine homeward they sway,

The boar’s head borne before the baron himself

Who killed it in the creek through craft of his hand

so strong.]

A few lines earlier, the romance describes the proverbial ferocity of this quarry, big game only marginally less dangerous than the aurochs or the bear (ll. 1571–80):

He gete þe bonk at his bak, bigynez to scrape,

Þe froþe femed at his mouth vnfayre bi þe wykez,

Whettez his whyte tuschez; with hym þen irked

Alle þe burnez so bolde þat hym by stoden

To nye hym on-ferum, bot nege hym non durst

for woþe;

He hade hurt so mony byforne

Þat al þugt þenne ful loþe

Be more wyth his tusches torne,

Þat breme watz and braynwod bothe.

[He gets the bank at his back, starts to gouge ground;

Froth foamed from his mouth, foul around jowls

While he whets his white tusks, filling with fear

All the hunters so hearty who crowd in around.

They a...

Þe froþe femed at his mouth vnfayre bi þe wykez,

Whettez his whyte tuschez; with hym þen irked

Alle þe burnez so bolde þat hym by stoden

To nye hym on-ferum, bot nege hym non durst

for woþe;

He hade hurt so mony byforne

Þat al þugt þenne ful loþe

Be more wyth his tusches torne,

Þat breme watz and braynwod bothe.

[He gets the bank at his back, starts to gouge ground;

Froth foamed from his mouth, foul around jowls

While he whets his white tusks, filling with fear

All the hunters so hearty who crowd in around.

They a...