![]()

V

ORGANIZATIONAL PERSPECTIVES

THE ORGANIZATIONAL ARRANGEMENTS WHICH TAKEN Together constitute the health system are many and varied. This is a further reflection of the system’s complexity. There are several different ways in which these arrangements can be characterized for purposes of understanding and comparing them. One is in terms of the nature of the organization-client (consumer) relationship. Certain types of organizations —for example, the private medical practitioner —have a direct relation to a “patient” and their major focus is on his level of health. The exchanges that take place in this situation, the laws, the traditions, and the normative expectations surrounding them are different than they are for organizational arrangements that are supposed to relate to the “community as a whole.” Though the latter also deal directly with individuals who may be in need of information or care, their primary concern is said, somehow, to be with the level (distribution) of health in the community, and the exchange that occurs has a different meaning both to the participants and to those who might be evaluating them. Thus, in these types of organizations the criteria for judging efficiency and effectiveness, for example, will be different than in the case of the former. Using this same scheme, other types of organizational arrangements in the health system are more difficult to place, e.g., professional schools and associations, laboratories, voluntary associations, and certain federal and state agencies. The relation of their activities to the ultimate consumer is more indirect.

Another way to view the various organizational forms is implicit in the word system itself. We have been talking about health as a system, a patterned arrangement of activities and values loosely linked by virtue of their various contributions to a common output. In such a model, organizations are subsystems or constituent units of the over-all health system and they may be identified according to their contribution to this over-all system.

Open systems theory tells us that system maintenance and performance—the taking in of resources (input), the transformation of these resources into services or goods, and the exchange of these “products” (output) with the environment—requires that certain functions be fulfilled: production, support, maintenance, and adaptation.* Production, as the name implies, is activity involved in the direct transformation of resources—skills, knowledge, capital, and equipment —into services or goods for the ultimate consumer or client, i.e., the “patient” or the community. Here we might place such diverse organizational arrangements as private or group practice, hospitals, and at least portions of local health agencies, clinics, laboratories, etc. Other organizations such as professional associations, voluntary associations, and state and federal health bureaucracies provide more of a support function since they help relate the health system to the larger political-economic environment of the society and help generate resources as well as legitimacy for it. A portion of the maintenance function —the training, indoctrination, and socialization of “actors” in the system— is fulfilled by colleges, universities, and other educational institutions that are turning out skilled, motivated human resources. Another portion, that of controlling the over-all system and allocating rewards and sanctions within it, is the function of certain political and administrative bodies as well as some professional associations. The adaptive function is clearly provided by the organizational subsystems involved primarily in planning or basic and applied research. Such organizations help the total system anticipate and adapt to social, scientific, and technical change.

It is clear that these distinctions are not watertight nor were they meant to be. Some organizations, for example, perform several functions. The hospital can be a teaching and research institution as well as a place for providing health care directly to patients. Professional associations are concerned not only with relating occupational segments of the health system to the larger society but also with exerting a certain degree of control over other organizations in the system. It is also clear that though these diverse structures can be said to be contributing to a central output—public health —in their actual day-to-day operations most do not consciously view their activities in the way we have been characterizing them here. In fact they concentrate on more discrete goals, suboptimizing in terms of them often to the disadvantage of the health system as a whole. The conception presented here provides a rough way of relating the variety of organizational arrangements to each other and to the notion of a health system.

Such a perspective is doubly necessary because the essential unity of the chapters in this part, which deal with several discrete conceptual schemes and apply them in a variety of organizational contexts, would be missed. These essays are about small parts of the total organizational complex constituting the health system. They have in common the fact that each deals with a problem at a fairly micro level. That is, the concern is with a single type of organization or even with only a very limited aspect of one type of organization rather than with the more macro problem of the health system as a whole. They differ in terms of the dimension on which they are focusing, e.g., decisionmaking, economies of scale, and cost-benefit analysis. They also differ in terms of the intentions of the individual authors. Some, such as those writing about decision-making or the life cycle of a health agency, are concerned with providing further theoretical and descriptive insights into more general organizational phenomenon. Others are more interested in marshaling empirical data for testing (in a loose sense of the word) some particular theory or model. Still others are seeking to provide rather pragmatic tools and analytic concepts that might have some immediate, if limited, use in administration. They should be read as individual essays but understood in this broader perspective.

* Daniel Katz and Robert L. Kahn, The Social Psychology of Organization, New York: Wiley, 1966, especially Chapter 3.

![]()

18

The Life Cycle Dynamics of Health Service Organizations

David B. Starkweather & Arnold I. Kisch

Most descriptions of health service organizations presume that these agencies exist in a static state. In fact, however, they are in constant evolution. One of the leading students of formal organizations has stated: “The only permanence in bureaucratic structure is the permanence of change in predictable patterns, and even these are not unalterably fixed.”1

What are these changes and how can they be described? Do they form a pattern which might be useful in predicting the future course of a specific organization? This chapter examines the “natural history” or “life cycle” of organizations in general and seeks to apply certain theories and findings of sociologists to health service institutions.

EFFECT OF THE EXTERNAL ENVIRONMENT

Life cycles of organizations are analogous to those of biological structures.2 Organizations may be thought of as having strong wills to survive. Stages of development from birth to death are evident. Some organizations have normal development while others apparently have arrested development. All are influenced by and have an impact on their environment.

Studies of health service organizations often focus on the changes that can be wrought through manipulation of internal features. The sociologist’s perspective, however, takes greater cognizance of the ecology of an enterprise—its relation to society at large and to the external forces which constantly exert pressure. These forces are often subtle and may go unrecognized. Yet the long-run success of an enterprise will depend more on its ability to adjust to changing values and demands of society than on administrative efficiency, particularly if this efficiency serves inappropriate or obsolete ends. The survival of an enterprise may become contingent on its readiness and ability to reorganize to adapt to changing conditions in society.

Some institutions appear to have greater control of their destiny than others. They more often take the initiative. Within the health services, those institutions that offer highly visible, dramatic, and valued services, such as the acute care general hospital, are in this category. They tend to endure despite their frequent low efficiency. Other health service organizations, such as public health departments, do not enjoy such well-articulated status. (For a discussion of organizations with intangible goals, see Warner and Havens.3) Their social worth is likely to be questioned even though they may be highly efficient in the sense that they seem able to make limited budgets go a long way. Public health programs additionally are very dependent on economic and political factors influencing their external environment. Treatment organizations, in contrast, are usually more self-contained and thus better able to direct their destinies from within.4

A BASIC DILEMMA

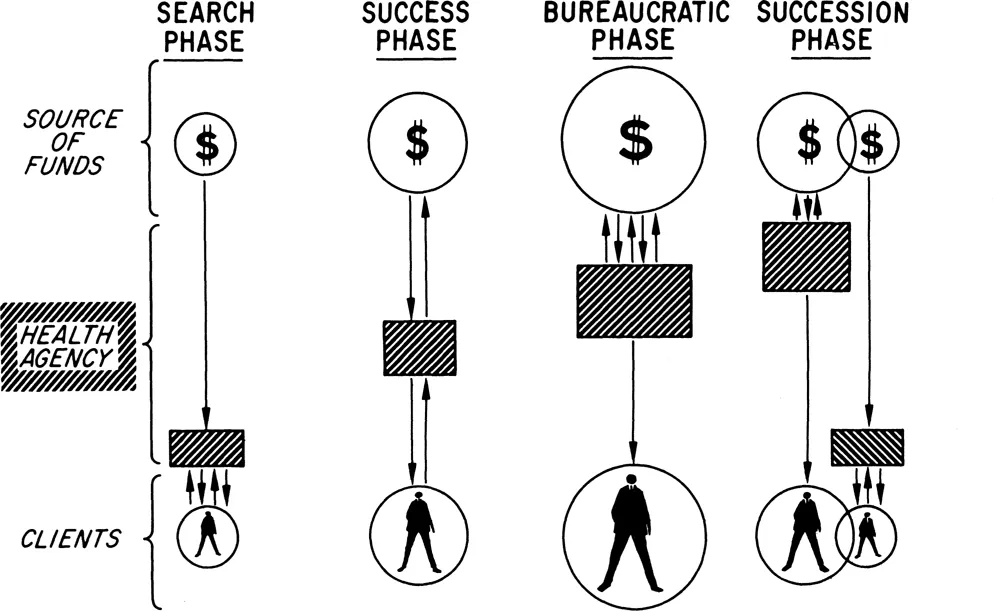

Service-oriented organizations are often caught between two sets of objectives: the organization’s desire on the one hand to serve its clients and its need on the other hand to serve its sources of financial support. Only in a few organizations are these objectives compatible. For most organizations they pose a dilemma. In this chapter we present four phases of a typical health service organization’s natural history and describe these phases in terms of the relative pressures brought to bear in each by the organization’s commitment to these two sets of objectives.

In economic terms this is called the separation of consumption and control, and enterprises may be classified according to the degree of control exerted by the consumer. It is high in small businesses, lower in large businesses, weak in oligopolies or private monopolies, and nonexistent in public monopolies such as the post office.5 One would think that medicine, particularly private practice, would rank high on the consumer-controlled list. No relationship would seem more personal and direct than the doctor-patient relationship. Yet it is the nature of a profession to say that the provider rather than the buyer “knows best” and, therefore, must control the relationship. Thus most medical and health-related institutions rank low in consumer control and rank close to public monopolies in the amount of true leverage possessed by the user.

Health service organizations are not fully described by traditional economic theories of the firm. Nevertheless, they too must respond to the relative pressures of client (patient) service versus financial support and allocate their resources accordingly.

Figure 1 presents in diagrammatic form the life cycle of a typical private medical or health agency.

There is of course the inherent danger of oversimplification in a diagram such as Figure 1 and in the interpretations that follow. Features attributed to one phase in the cycle are in fact part of a time continuum. And we do not imply that the sequence and relationships diagramed in Figure 1 always occur under every condition or that no other factors are involved. Yet a certain artificial sharpening of the boundaries in the evolutionary process may enhance appreciation of the manner in which organizations change. This typology should properly be viewed as a point of departure in a realm where virtually no systematic studies have been conducted.

PHASE I: THE SEARCH PHASE

In this phase of its life cycle an organization is of course young and small, having been created in response to the pressure of social forces. As described by Sheldon Messinger, the organization is in ascendancy, resulting from the concern of its leaders and members that something be done to transform social discontent into effective action.6 The rate of innovation is high, permitting policies or procedures to be quickly modified as personnel seek the proper approach to problems that first generated the organization’s formation. Patients or their representatives are formally or informally included in the decision-making process of the organization, and their suggestions and criticisms are sought with genuine interest.

At this stage there is much jostling, bargaining, and latent competition between the new agency and better established enterprises within the community, with each organization seeking its most favorable posture relative to the others. The new agency examines its own capacity and the world around it to discover where its services can most effectively augment the existing pattern, where financial resources are to be found, and upon whom these financial resources are dependent. At this early stage a maximum proportion of the agency’s resources are devoted to service, since it is through this mechanism that the agency seeks to secure a firm position in its environment. Organizational decisions made at this point will have an important influence on the entire future course of the institution since important commitments have to made during these formative times. The role developed for the organization in the end actually may be forced from the outside rather than acquired by deliberate design from within.7 If however a role acceptable to society cannot be developed at this stage, the agency will likely die.

The administrative structure of an agency at this phase is informal and open. The staff is growing, and there must be a...