eBook - ePub

Japan Emerging

Premodern History to 1850

Karl F. Friday

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 498 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Japan Emerging

Premodern History to 1850

Karl F. Friday

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Japan Emerging provides a comprehensive survey of Japan from prehistory to the nineteenth century. Incorporating the latest scholarship and methodology, leading authorities writing specifically for this volume outline and explore the main developments in Japanese life through ancient, classical, medieval, and early modern periods. Instead of relying solely on lists of dates and prominent names, the authors focus on why and how Japanese political, social, economic, and intellectual life evolved. Each part begins with a timeline and a set of guiding questions and issues to help orient readers and enhance continuity. Engaging, thorough, and accessible, this is an essential text for all students and scholars of Japanese history.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Japan Emerging un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Japan Emerging de Karl F. Friday en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Politics & International Relations y Asian Politics. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

PART I

Landmarks, Eras, and Appellation in Japanese History

1

Japan’s Natural Setting

A COUNTRY OF MOUNTAINS

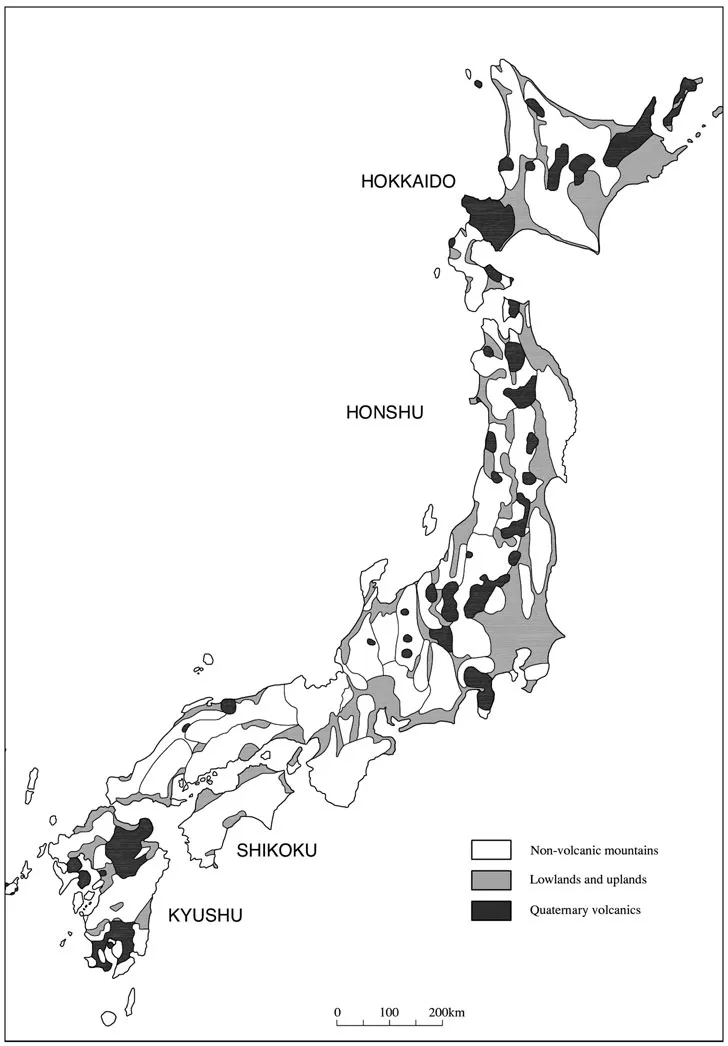

Arriving in Japan at Narita or Kansai airport, one would hardly guess that mountains are the dominant topography of Japan. Far in the distance, a thin purple undulation of skyline tells differently. Satellite photos reveal an archipelago of steep, solid-green mountains and precipitous valleys across the four main islands: Hokkaido in the north, then Honshu, leading to Kyushu, with Shikoku nestled between (see figure 1.1).

Tectonic History

This archipelago is of relatively recent formation: it detached from the edge of the Eurasian continent only about 15 million years ago upon the opening of the Japan Sea. Surprisingly, the Japanese landmass was relatively flat when it detached.

The current mountains are products of tremendous tectonic stress, as the archipelago sits at the edge of the continental Eurasian Plate, facing two offshore oceanic plates—the Pacific Plate in the north and the Philippine Plate in the southwest. The continental plate is moving eastward, while the oceanic plates head westward, causing the islands in between to buckle and uplift into folded mountains. The landmass is still rising and the mountains are becoming higher, leading to one of the greatest rates of erosion in the world. Short rivers cut down steeply from the mountainous backbones of the islands, dumping their heavy sedimentary loads into the seas.

Figure 1.1. Japan and its mountains, most of which are folded along the axis of compression. The coasts and rivers are bordered by flat alluvial lands, but the uplands consist mainly of sloped or hilly volcanic deposits. (Prepared by Durham Archaeological Services after Yonekura et al., Nihon no chikei 1, fig. 1.3.2.)

This meeting of the plates also creates a subduction zone, where the oceanic plates are being drawn down (subducted) underneath the edge of the continental plate. Volcanoes and earthquakes are the result—constant menaces to life in the Japanese islands. The earliest volcanoes in the newly formed archipelago erupted around 14 million years ago, ranging across the Inland Sea area in western Honshu. About 2 million years ago, great volcanic explosions occurred in the Tōhoku region of northern Honshu; these left great collapsed calderas in the landscape, more than twenty kilometers in diameter, that now form some of the favorite crater lake tourist destinations, such as Lake Towada.

The current series of volcanic eruptions began around 700,000 years ago in three distinct areas: from Hokkaido through Tōhoku to central Honshu, from Tokyo south through the Izu Islands including Mt. Fuji, and north-south through Kyushu. Today, Japan claims about 10 percent (one hundred or so) of the world’s active volcanoes, including Sakura-jima at the southern end of Kyushu. Nevertheless, volcanoes actually form a small proportion of all the mountains in Japan (see figure 1.1)—most of which are tectonically folded mountains.

New Coastal Plains

The contrast between mountains and plains is abrupt: the change in slope is often steep (35–40 degrees), wooded mountainsides meeting gently sloping (1–2 degrees) flatlands. Statistics vary: some say Japan is 86 percent mountains and 14 percent plains, while others measure 65 percent mountains and 35 percent plains. The difference lies in what is considered a plain (heiya). The coastal fringing plains are relatively flat, but the great Kantō Plain around Tokyo is actually a rolling dissected volcanic terrace landscape, while Hokkaido, northern Kantō, and southern Kyushu are characterized by broad volcanic slopes and plateaus. Add these volcanic uplands to the alluvial plains, and the percentage of “flat” land goes up. Thus, as a rule of thumb, everything but steep mountains fits in the category of 35 percent plains, and we can distinguish uplands, terraces, levees, and alluvial flats within that category.

The coastal plains that fringe the islands are relatively recent, emerging only when the high sea levels of the postglacial Climatic Optimum (6,000–4,000 years ago) receded. Groups of hunter-gatherers, the Jōmon, exploited the mountains (for hunting and gathering and some horticulture) and seashores (for shellfish collecting and coastal and deep-sea fishing). Soon thereafter, however, in the early first millennium BCE, rice agriculture was adopted from the continent. From that point onward, the plains became the focus of settlement, agricultural exploitation, and urban development.

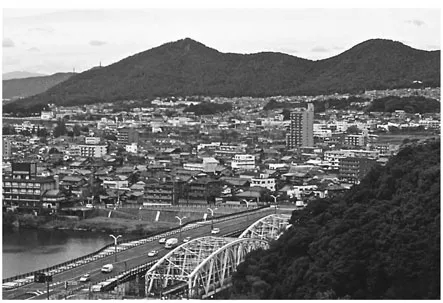

Figures for today’s Japan make it the fifth most densely populated country in the world, at an average of 343 persons per square kilometer. Nevertheless, this average is taken across virtually uninhabited deep mountains and solidly residential plains (figure 1.2). The density for Tokyo is 5,751 persons per square kilometer, seventeen times the “average” but indicative of the imbalance between mountains and plains. With so much population concentrated in the lowlands, mountain areas have been relegated to places of leisure: skiing, soaking in hot springs, viewing cherry blossoms. For the majority of the Japanese population, living in their national heartland is an unknown experience (figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2. The city of Nagoya spreads over coastal plains and lower slopes, but the virtually uninhabited mountains behind rise abruptly. Remnants of the previous border between plains and mountain slopes can be seen in a series of isolated woods along the terrace paralleling the greenbelt line. (Author’s photo, November 2008.)

A COUNTRY OF PADDIES AND DRY FIELDS

Historically, agriculture in Japan has been divided into upland crops and lowland rice paddies. Both uplands and lowlands are ecological areas subsumed under the term “plains,” but their constituents are radically different. Uplands do not include steep mountain slopes, but in general the term refers to the rolling, eroded surface of volcanic terraces, riverine levees and terraces, and basin flanks. “Lowlands” generally refers to alluvial bottomlands and coastal flatlands. Over time, paddy fields have encroached on the uplands, but this is a trend now in reversal.

Rice Paddy Landscapes

Once wet rice agriculture was initiated in Japan, paddy field construction greatly modified the natural topography of lowland Japan. The nature of the soil was less important than the control of water: Rice paddies need to be leveled in order to maintain an even water depth for nourishing the rice during the three growing months. Thus, coastal plains of gley soils having small slope gradients were the first to be exploited from the beginning of the Yayoi period, in the early first millennium BCE. Rice paddies were initially carved out of river bottomlands, near sources of irrigation water, but these were often subject to floods. With the advent of iron digging tools in the early first millennium CE, coarse sediments of lower basin flanks could be cultivated and irrigation canals built to supply them with water.

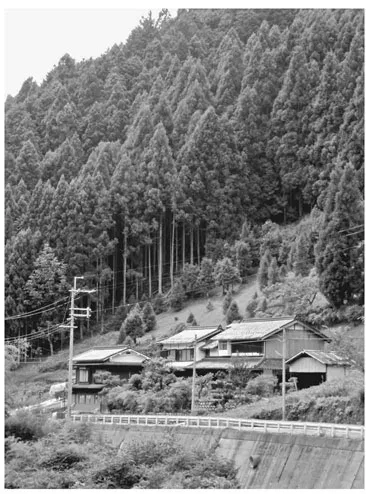

Figure 1.3. An isolated residence in the Yoshino River Valley, Nara Prefecture, located on a steep slope hosting a Japanese cedar (sugi) plantation. (Author’s photo, August 2008.)

The first large-scale transformation of the lowland landscape, however, occurred in the seventh to eighth centuries, when the Yamato court adopted Chinese-style ruling technologies from Tang China. One of the innovations was the surveying and laying out of both agricultural land and cities on a grid framework, the jōri system. The gridded paddy fields, about one hectare in size, could then be subdivided into smaller units and allocated to individuals for rice tax purposes. The jōri layout can still be seen in the ever disappearing fields of the Nara Basin and in other areas of the Kinai, a regional designation for the “home provinces” of old Yamato now subsumed in Osaka, Kyoto, and Nara Prefectures.

Terracing of lower slopes and river valleys (of 5 to 6 percent slope) began in the seventh century. Only in the medieval period, however, as irrigation technology advanced, did terracing begin in steeper river valleys, with a gradual extension onto hillslopes (up to 16 percent gradient). This, in effect, pushed the forests farther up the mountains and increased the amount of arable land near the lowlands. In the Edo period, rice-growing was also extended onto volcanic soils in the Kantō region around Tokyo, a development facilitated by the digging of irrigation canals to supply both water and nutrients. In the nineteenth century, marginal lands including tidal flats, estuaries, lagoons, and some inland lakes were reclaimed for rice cultivation. For instance, Kyoto basin used to have a large lake near the juncture of the Yodo and Uji rivers that was eventually reclaimed for use as paddies.

The maximum extent of paddy land in Japan was reached in the early 1930s. Thereafter, the area devoted to rice production decreased with changing food preferences, including imported rice. In the inland mountain valleys, abandoned paddy fields are being recolonized by forest, while former paddies on valuable coastal plains have been consumed by urban expansion. Some of the large conurbations that now characterize many coastal areas have entirely obliterated the natural plains (Osaka, Kobe), and mountain basins are filling in fast with urban sprawl (Kyoto, Nara). Some municipalities have enforced greenbelt areas along the foot of the mountains, protecting the forests on the slopes, while others have encroached on lower foothills, blurring the distinction between plains and mountains. So the traditional landscape once demarcated between forest and paddy is now recast between forest, paddy, and conurbation.

Between Paddy and Forest

In contrast to lowland paddy fields, lands beyond the plains were highly diverse in the premodern period. Forests were traditionally distinguished by proximity to settlements: Okuyama (inner mountains) were places for hunting and collecting—rich in animal and plant (often nut) resources—while satoyama (village mountains) were forested areas near settlements and heavily exploited for wood for fires and tools; these trees were often chopped down and burned to provide more field space for dry crops. This latter pattern, referred to as slash-and-burn or swidden agriculture, lasted into the 1970s but is rarely seen today.

The deep mountain forests are discussed in a later section. Here let’s look at the various forms of uplands within the plains that sustain dry-field crops, orchards, and vegetables. These plantings are often found around settlements, which were traditionally sited on high ground to avoid flooding. Even on alluvial flats, villages sat on natural river levees, and these natural levees also supported vegetable gardens. The difference in height between a paddy field and a vegetable garden could be as little as half a meter—reflecting the difficulty of lifting irrigation water up onto the levee.

A specific sector of Japanese plains is the volcanic terrace as seen in the Kantō Plain. The entire Kantō region, where Tokyo is sited, is such a terrace, comprising thick layers (some three hundred meters deep) of volcanic ash deposited in the Pleistocene period more than 10,000 years ago. Large rivers such as the Tone, Arakawa, and Sumida have washed out great portions of these layers. At the Nippori station on the Yamanote train line in Tokyo, one may see bluffs carved out by the Arakawa River towering above the tracks. Situated on these bluffs are Edo-period temples and their cemeteries, Tokyo University, and the Ueno Park complex, including several national museums. When the Tokugawa established Edo as its capital, the bluffs were virtually unoccupied, with most activity carried out by fishing villages along the shore of Tokyo Bay. Thus developed the social distinction between the aristocratic occupation of the upper terraces now served by the Yamanote (hill-fingers) circle line and the commoner habitation of the coastal lowlands of shitamachi (lower town). But why were the bluffs previously unoccupied?

Volcanic soils in areas of high precipitation like Japan are notoriously poor in nutrients. The rain leaches out the calcium, magnesium, and potassium, and an unusual colloidal fixing of phosphate in volcanic soils also makes this element unavailable for plant growth. The absence of these vital nutrients from the Kantō Plain, plus their being too high above the streambeds for irrigation, made them poor for agriculture. Many volcanic soils around Japan, particularly on the flanks of volcanoes, are virtually unused for crops. They are often colonized by bracken, sasa bamboo, and pampas grass, as seen on the northern flanks of Mt. Fuji—used for filming galloping-samurai movies. Only with irrigation and fertilization have they been brought into production. Vegetables, particularly root crops such as radishes, carrots, and sweet potatoes, grow well in the fine-grained volcanic soils; orchards are another good investment, as in the thick deposits of white pumice of southern Kyushu.

Despite the image of Japan as a country of rice agriculture, in the nineteenth century before urbanization and industrialization, rice paddy accounted for 58.5 percent of the arable land, while dry fields amounted to a full 41.5 percent. To ignore the prominent role of dry crops in Japan’s agricultural history is to misunderstand the life of the peasants, who were often barred from eating the rice they grew and were forced to subsist on dry crops such as barley and millet, and vegetables from their gardens.

A COUNTRY OF CLIMATIC EXTREMES

The Japanese archipelago, including the Ryūkyū Islands in the south, forms an arc that stretches from 45°30" to 20°24" north latitude. In North American terms, this is from Augusta, Maine, to Nassau in the Bahamas; in European terms, from Bordeaux, France, to the Aswan Dam on the Nile; and in Australian terms, from Brisbane in the north to Tasmania in the south. The archipelago thus stretches between cold temperate and subtropical regimes, so it is no surprise that Hokkaido is cool in summer and snowed over in winter, while Okinawa basks in mild temperatures year-round.

Japan, however, also has clear east-west differences in climate. It is a monsoonal country with seasonal influences of oceanic and continental regimes. In the summer, onshore winds from the Pacific Ocean bring heavy rain in June and typhoons from July through September; in winter, offshore winds from the continent bring cold air down from Siberia. These wintertime winds, however, are moderated by both the sea and high mountains. The dry, cold winds pick up moisture crossing the Japan Sea; then, as they are forced upward over the backbone of the mountain ranges, they drop their precipitation as snow. Thus, the northwestern flanks of Honshu and the high mountains suffer under heavy snowfall, while the eastern seaboard enjoys a maritime winter with relatively mild temperatures. The now dry winds, however, signal a deprivation of moisture, making winter in the eastern mountain flanks a time of forest fires.

The western snowbound regions are known traditionally as Snow Country, also the title of a novel by Kawabata Yasunari. The protagonist views a winter escape to the Snow Country as an antidote to city living. Not only did time slow down relative to other regions, because deep snow made getting about extremely difficult, but people living in these regions developed distinct customs to accommodate the snow. The children’s snow “igloos” of Akita Prefecture are famous, and the Niigata Prefectural Museum gives an adult view of living with ten feet of snowpack in winter.

Average annual precipitation in Japan ranges from 944 to 4,060 millimeters, but usually exceeds 1,020 millimeters. This rate puts Japan on a par with South China, the Congo, and Brazil but is not as high as Indonesia’s. One result of all this precipitation is a high rate of erosion of the land surface, as mentioned above; another is the acidification of volcanic soils as alkali and alkaline elements are leached away. A third is high humidity. In the dry winters, humidity can drop as low as 50 percent in Tokyo, but in summer, the humidity throughout the lower islands is often 98 percent even when it is not raining—all the more reason to escape to Karuizawa in summer, a famous mountain resort in central Honshu, or to Hokkaido for a cooler, drier summer.

A COUNTRY OF FORESTS

High precipitation also contributes to a lush growing season. The okuyama forests of Japan are dense, but their composition has changed over the centuries. Because of the north-south range of the islands, the climax forests in the northeast are cool temperate deciduous forests harboring familiar nut tree varieties such as chestnut, walnut, and deciduous oak. In the southwest, the climax forest was, until the arrival of agriculture, a laurelignosa forest similar to that in South China. This forest, largely unfamiliar to Westerners, consisted of evergreen oak, hinoki cypress (Chamaecypar...