Psychological Therapies in Acquired Brain Injury

Giles N. Yeates, Fiona Ashworth, Giles N. Yeates, Fiona Ashworth

- 200 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

Psychological Therapies in Acquired Brain Injury

Giles N. Yeates, Fiona Ashworth, Giles N. Yeates, Fiona Ashworth

Información del libro

The psychological impact of an acquired brain injury (ABI) can be devastating for both the person involved and their family. This book describes the different types of psychological therapies used to ameliorate psychological distress following ABI.

Each chapter presents a new therapeutic approach by experts in the area. Readers will learn about the key principles and techniques of the therapy alongside its application to a specific case following ABI. In addition, readers will gain insight into which approach may be most beneficial to whom as well as those where there may be additional challenges. Covering a wide array of psychological therapies, samples range from more historically traditional approaches to those more recently developed.

Psychological Therapies in Acquired Brain Injury will be of great interest to clinicians and researchers working in brain injury rehabilitation, as well as practitioners, researchers and students of psychology, neuropsychology and rehabilitation.

Preguntas frecuentes

1

APPLICATION OF THE COGNITIVE BEHAVIOURAL APPROACH TO ENHANCING EMOTIONAL OUTCOMES FOLLOWING ACQUIRED BRAIN INJURY (ABI)

Introduction

Theoretical and practical background to cognitive behavioural therapies

- A focus on personal meaning (as articulated in beliefs, assumptions and other forms of mental representation) as underlying a given issue: “The concentration on exploring the meaning of events throughout the course of therapy … should be encouraged” (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979, p. 33). We are heavily influenced by Teasdale and Barnard’s (1993) distinction between propositional and implicational meanings, with the latter being the target for change as implicational representations map rich, subjective, ‘felt sense’ of self-in-context.

- The notion that underlying meaning elicited in a type, or types, of situation is reciprocally associated with cognitive, behavioural, emotional and physiological processes, such that change in one domain might result in changes in other domains.

- The likelihood that some aspects of the cognitive, behavioural, emotional and physiological responses that arise in given situations might be related to personal historical factors, such as early experiences.

- There is a causal chain of processes linking responses in ‘trigger’ situations to longer term maintenance or deepening of problems (for example where the initial response in turn becomes a further ‘trigger’).

- Cognitive processes are not fixed, but dynamically shift according to the nature of currently active meanings and emotional processes (for example, a feeling of lack of energy might trigger a spiral of negative self-focused rumi-nation, once ruminating the person may become less able to think flexibly, problem solve or make more nuanced, less black and white interpretations of events, and memory retrieval becomes more over-general and negatively biased; see Mansell, Harvey, Watkins, & Shafran, 2008).

- It is relatively structured and time limited with the aim of achieving one or more specific aims identified by the client.

- There is a focus on the client practicing between sessions, as well as within sessions, in order to generate the desired shifts in meanings, emotions or behaviours.

- The general orientation is one of curiosity and exploration (originally described by Beck as ‘collaborative empiricism’), where the therapist works alongside the client rather than taking the ‘expert role’.

- The therapist informs the person about the principles of the CBT being used (providing information) and links the information to examples and practice in session (socialising to the model).

- The therapist fosters a collaborative rapport with the client within which new meanings can be identified and explored (typically using a model which summarises the key processes pertaining to a particular clinical problem area), allowing the client to begin to reflect on and organise their subjective experiences.

- The therapist wonders with the client about whether this formulation might help to identify areas to change in order to move towards their goals.

- This collaborative and reflective process sets the foundation for introducing specific techniques associated with that model or approach to treatment that address the core processes assumed to be generating vulnerability to, or maintenance of, the problem.

- Techniques are explained and practiced in session, and the client asked to reflect on their experience of using the technique and what changes or effects they think it might have.

- Therapy proceeds with developing and deepening specific practices, for example: identifying unhelpful thinking patterns in session then as homework, developing different ways of responding to these thinking patterns first in session then as homework, practicing the acts of catching and reflecting on unhelpful thinking until it becomes increasingly automatic.

- Whilst the targets are often cognitive in nature (thoughts, images, assumptions, beliefs, thinking styles such as catastrophising or personalising, processes such as rumination), interventions will necessarily involve behaviour change – manipulating behaviour in a specific trigger situation to explicitly test things out (‘behavioural experiments’: see McGrath et al., 2004).

- Every endeavour should be made to work with the client in emotionally ‘hot’ situations (evoked in a clinic-based session, in everyday life, at home, in relationships, or involving significant others; Beck et al., 1979).

- This may involve working directly with emotion (for example using a calming or compassionate image, increasing engagement in pleasurable activities and attending more fully to positive or other emotional experiences).

- Therapy endings are carefully planned to include a ‘blueprint’ for predicting and managing set-backs, ensuring continued change/consolidation post therapy and might include follow-up or booster sessions.

Application of CBTs when working in acquired brain injury

Targets for therapeutic change

- Some aspect of the ABI, or life after ABI, is a trigger for underlying beliefs and assumptions to be activated, in line with the traditional view of cognitive models of emotional disorders. Here an individual might present predominantly with a single clear emotional disorder (perhaps with some variation depending on the individual, their acquired deficits and circumstances). Specific evidence-based cognitive behavioural therapy based on the appropriate diagnosis-specific model might be applicable, albeit with modifications to address acquired cognitive or other difficulties.

- The new and challenging circumstances that arise post-ABI result in a mix of subjective experiences and symptoms such as disinhibited or uncharacteristic emotional reactions, altered sense of identity, or sense of loss of self, unhelpful coping (including ‘denial of disability’), low self-esteem (and low self-efficacy) and absence of (opportunities for) experiences that might contribute to new meaning-making. Research in to transdiagnostic factors has identified threat to self and emotion dysregulation as two common underlying processes across depression, anxiety and stress post TBI (Shields et al., 2016). For this group, we have developed two models, and related intervention targets and processes, based on the centrality of altered sense of personal and social identity to maintaining unwanted outcomes (Gracey, Evans et al., 2009; Gracey et al., 2015).

- In both these cases, unless the acquired deficits are relatively mild, life post-ABI is likely to be radically changed, and individuals may need support to move beyond resolution of disconnection with self, or threat to self, to achieving sense of purpose, finding positive meanings, (re)connecting with self and others in everyday life (Ownsworth & Gracey, 2017). A broader conceptualisation of ‘outcomes’ than resumption of activity or reduction of ‘symptoms’ is required; one that allows for entry into the unknown, to be open to exploration and discovery of new meanings that may arise despite, or perhaps because of, the challenges being faced (for example as described in models of Post-Traumatic Growth: Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004; Powell, Ekin-Wood, & Collin, 2007; Silva, Ownsworth, Shields, & Fleming, 2011). Intervention approaches may be more concerned with finding the conditions in which someone can explore and develop new and valued meanings in life. Whilst CB techniques (such as ‘possibility dreaming’: Mooney & Padesky, 2000) could be used to support ‘constructive’ work (Gracey, Brentnall, & Megoran, 2009) there is a growing body of evidence concerning approaches drawn from other schools of thought (e.g., positive psychology: Cullen et al., 2018; arts: Ellis-Hill et al., 2015; Baylan, Swann-Price, Peryer, & Quinn, 2016; and mindfulness: Bédard et al., 2014), which could feature as part of a broader constructive rehabilitative endeavour.

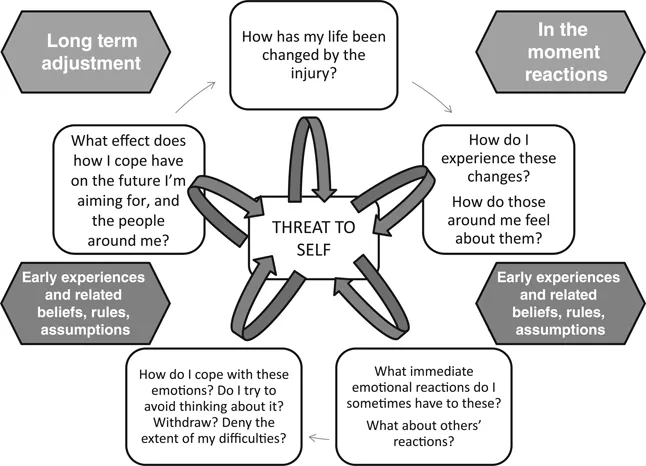

A transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural approach to working in ABI

- The transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural model of adaptation post-ABI (Gracey et al., 2015) describes the ways in which immediate understandable momentary emotional reactions in the context of changed life post ABI can be made sense of in terms of ‘threats to self’, echoing Goldstein’s (1952) description of the psychological consequences of ABI. The model distinguishes between a number of linked cognitive-behavioural processes. These include pre-injury factors (including assumptions and rules for living, coping styles) that might pre-dispose someone to experience certain post-injury challenges as a particular ‘threat-to-self’, the actual changes someone faces, in-the-moment threat reactions triggered when faced with challenges, effects of self-regulatory deficits and longer term meaning-making and coping patterns (e.g., avoidance, emotion-focused, substance misuse, attempts at mental or emotional control, acceptance) that ultimately further influence that person’s everyday circumstances. We broke the full model down into a more accessible ‘vicious daisy’ as a potential tool for facilitating collaborative formulation, presented (with permission) in Figure 1.1.

- The Y-Shaped model (Gracey, Evans et al., 2009; Ownsworth & Gracey, 2017) describes the conditions under which rehabilitation activity and identity change can be brought together in a relatively structured process to help reduce sense of discrepancy and disconnection, and in time develop personal and social (re)connections and new ways of being in the world. The emphasis is on progressive cycles of exploration linking as necessary with rehabilitation activities in personally valued roles or contexts. The most recent version of the model is influenced by the phenomenological model of wellbeing described by Galvin and Todres (2011) and observations working on a trial of an Arts and Health intervention for confidence post-stroke (Ellis-Hill et al., 2015): ensuring that the contextual conditions are right for ‘stepping into the unknown’ and creatively discovering new insights and meanings.

FIGURE 1.1 The ‘threat-to-self vicious daisy’ model providing a simplified version of the transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioural model based on Gracey et al. (2015), adapted with permission from Routledge Press.

FIGURE 1.1 The ‘threat-to-self vicious daisy’ model providing a simplified version of the transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioural model based on Gracey et al. (2015), adapted with permission from Routledge Press.