eBook - ePub

How the War Was Won

Command and Technology in the British Army on the Western Front: 1917-1918

T.H.E. Travers

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 268 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

How the War Was Won

Command and Technology in the British Army on the Western Front: 1917-1918

T.H.E. Travers

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

"How the War Was Won" describes the major role played by the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front in defeating the German army. In particular, the book explains the methods used in fighting the last year of the war, and raises questions as to whether mechanical warfare could have been more widely used. Using a wide range of unpublished

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es How the War Was Won un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a How the War Was Won de T.H.E. Travers en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Storia y Storia mondiale. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

Paralysis of command: from Passchendaele to Cambrai

The battle of Passchendaele revealed several fundamental planning and command errors as the campaign unfolded. Particularly obvious errors were the choice of the Passchendaele area as a battlefield; serious confusion over the objectives of the offensive, and the continuation of this confusion as the battle progressed; ambiguity over the type of offensive that was to be fought; the choice of Gough to command the offensive as GOC Fifth Army; and the continuation of the offensive in late 1917 when all hope of useful results had gone. In terms of the objectives of the Passchendaele offensive, it is worth pointing out that there were at least three aims expressed by Haig: reaching and clearing the Belgian coast; wearing down the enemy in preparation for a decisive offensive; and capturing the Passchendaele Ridge and the village of Passchendaele. (It is also worth noting that attrition—the killing of more enemy soldiers than BEF soldiers—was not one of Haig’s specific aims.) By the time that the Cambrai offensive commenced in late November, the first aim had not been achieved, the second had been achieved only partially and the third was in the process of being achieved. Cambrai itself is well known as the first major tank offensive in the history of warfare, but after an initial remarkable success, the Cambrai attack also lost focus, realistic objectives were abandoned and, like Passchendaele, the offensive was carried on too long. Command failures then led to a reluctance to prepare for a German counter-attack, and subsequently the BEF high command failed to recognize the significance of the new German tactics used in the counter-attack, which would be employed on a larger scale in the spring of 1918.

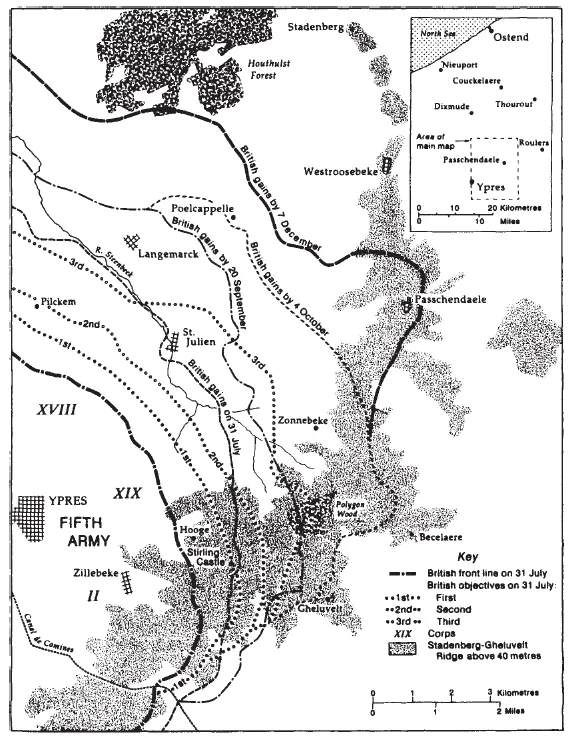

The battle of Passchendaele, (Map 1.1), commencing on 31 July 1917, was flawed from the very beginning. One difficulty was that Haig, just as he was to do before the March 1918 German offensive, became overconfident and expected that the war could be won in 1917. It is true that there was some justification for this belief, since in 1916 the German Fifth Army had suffered some 572,855 casualties at Verdun between 21 February and 10 September 1916. Of these 75,000 eventually returned to the front from field hospitals, as did another 275,770 from temporary aid stations, but the casualty list was still formidable. In addition, there were approximately 500,000 German casualties at the Somme in mid- and late 1916. However, Haig overlooked the fact that in 1917 the German army had gone onto the defensive, and also planned to conserve manpower through new defensive tactics. Thus Haig was mistaken when he told Robertson in early June 1917 that Germany was nearly at its ‘last resources’, and mistaken when he told the War Cabinet later in June that Germany was within six months of total exhaustion at the present rate of progress. By mid-July Haig was informing Rawlinson that all one had to do was press the Germans on all fronts, and the war could well be finished in 1917.1 Because of this confidence, Haig did not seem to be worried by some obvious problems that he actually admitted soon after the battle commenced; for example, that the front of the attack was too narrow; that the Germans had good artillery observation over Fifth Army positions, while his own guns were unavoidably exposed; and that the ground on the right was unfavourable for the attack.2 Moreover, it is curious that Haig did not exploit the Messines success that had occurred earlier in June, and which his commanders Plumer (GOC Second Army) and Jacob (GOC II Corps) both wanted to pursue.3

Another major difficulty was that the objectives for the Passchendaele offensive went through several changes before Haig informed his army commanders on 5 July 1917 what the final plans were. Originally, in January, the idea had been to rush the offensive right through to clear the Belgian coast. This was modified, although mainly in order to reach the coast in stages, yet at the same time it was intended to capture the Passchendaele Ridge. Now there was some doubt as to which was the primary objective. In the end, Haig wanted to do both, and therefore neither objective was given the full attention it deserved. Haig’s instructions on 5 July read that the Fifth Army would secure the Passchendaele Ridge, then after ‘very hard fighting lasting perhaps for weeks’ there would be more rapid progress northeast to gain the line Thourout-Couckelaere, where the offensive would continue north to join up eventually with a Fourth Army offensive along the coast from Nieuport to Ostend. There was also to be an amphibious landing, with tanks, on the coast, but this would take place only if the main Passchendaele offensive had already made the coast ‘practically untenable’ for the enemy. Haig also wrote that the first aim of the offensive was to drive the enemy off the ridge from Stirling Castle to Dixmude, which was puzzling since Dixmude was not part of the ridge, but was far to the north and could not have been part of the Fifth Army offensive, or even of the French participation on the north flank. However, the net result of these several objectives was that some of the key figures involved, including Haig, Plumer and Jacob, were more concerned with the immediate problem of capturing the Passchendaele Ridge, while others, such as Gough, Rawlinson, Davidson and Robertson, were more involved with what type of offensive 31 July would be—either a rush-through, or a step by step, limited objectives, advance.4

Map 1.1 The battle of Passchendaele, 31 July 1917

In regard to the first problem—the emphasis on the ridge—one incident is of telling interest. This occurred when Haig told Rawlinson in early July 1917 that the key to Gough’s attack was the Stirling Castle—Becelaere ridge (essentially the Passchendaele Ridge), and that this must be taken first before any other advance took place, and Rawlinson agreed but said that more important was the question of limiting Gough’s objectives in the offensive. In fact, the problem of the ridge was directly related to the other problem, the breakthrough, or a step by step advance. Not only was the ridge a very formidable defensive obstacle, but there were particular problems on the right of the ridge, where not all of the high ground was included in the offensive, thus producing a vulnerable right flank. This was recognized by Davidson, who on 25 June 1917 bluntly told Major General Clive (British Liaison Officer at GQG, the French Army Headquarters) that Tactical difficulties of [the] Right flank make [the] idea of [a] big thrust hardly realisable.’ This forthright appraisal either was not relayed to Gough, or did not make him alter his perception of the requirement for a breakthrough. Similarly, Haig either did not, or could not, impress on Gough the significance of the right of the ridge. Gough was simply not perceptive enough to take Haig’s advice and see that the great weakness of his offensive was on the right flank. Even when the offensive was predictably held up on the right, Gough refused an offer from XIV Corps of an extra division for that flank, saying ‘If you can’t get on in one place, you must get on in another.’5 Unfortunately, this was just what could not be achieved and Fifth Army suffered heavy losses for the next month from problems on the right flank. Moreover, Haig further compounded the ambiguity of his offensive plans by his instructions to Gough, which were both to have a distant objective and to wear down the enemy. Not surprisingly, Gough was puzzled, but certainly still believed that he was meant to undertake a breakthrough.

Nevertheless, the basic choice for Passchendaele of a rush-through offensive (as Gough termed it), versus a limited series of advances, should have been a clear decision by Haig. It would seem that Haig was torn between his optimistic desire to achieve a striking success and, on the other hand, the limited objectives type of advance urged on him by a number of sources, including Davidson, Rawlinson (GOC Fourth Army), Robertson and the War Cabinet, which received backing from the forecasts of his chief of intelligence, Charteris. Yet Haig allowed Gough to go ahead with a rush-through style of attack, despite misgivings by other senior commanders. For example, Rawlinson’s diary entries at this time are very instructive, starting with 25 June 1917 when Rawlinson learned for the first time of discussions at GHQ regarding an unlimited attack. On 29 June 1917, Rawlinson had a long talk with Robertson and advised him to ‘hold on to Goughie’s coat tails and ordering him [Gough] only to undertake the limited objectives and not going beyond the range of his guns’. Then on 3 July 1917, Rawlinson talked with Haig and

urged him to make Goughie undertake deliberate offensives without the wild ‘hurooch’ he is so fond of and leads to so much disappointment. The rule is that they must not go beyond the range of their guns or they will be driven back by counter attacks. I am not sure that DH [Haig] will insist on this with sufficient strength and I fear that if he does not the attack may fail with very heavy losses.

No doubt Rawlinson was remembering his own problems at the Somme, but his advice was ignored and on 21 July 1917 Gough declared that he was optimistic his Fifth Army would be able to get the (second) green line, and also, he hoped, the (third) red line, on the first day. (As it turned out, the red line was not obtained in the centre and south of the attack until 20 September 1917.) On 30 July, the eve of the offensive, Gough expressed great optimism that the attack would be a ‘sitter’ (that is, a sitting or easy target), but after the costly difficulties of the actual offensive of 31 July 1917, Rawlinson was able to report on 1 August 1917 that Haig had finally decreed limited objectives and ‘no Huroosh! I am glad we have learned this at last.’ Finally, on 5 August 1917, Rawlinson wrote that Gough was converted from his ‘hurrush’ style of attack to limited objectives, although on 9 August 1917, Rawlinson and his chief of staff, Montgomery, still felt it necessary to send a memo to GHQ outlining the utility of limited objective attacks, especially because of German defence in depth and counter-attack tactics.6

Why couldn’t Haig, as commander-in-chief, control his army commander, Gough, when setting objectives for the Passchendaele offensive of 31 July 1917? Partly because Haig himself evidently wanted to try a breakthrough offensive, which he had espoused as far back as January 1917, saying then that the ‘whole essence is to attack with rapidity and push through quickly’; partly because Haig had accepted the advice of Plumer to try for a breakthrough; partly because Gough would not take advice; and partly because of Haig’s belief that army commanders should be left to run their own battles.7 This last point is also illustrated by the possibility that the troublesome right flank of the offensive might be solved by attacking the area from the south and southwest. This plan was given to Gough by Haig, but Gough refused to do it, and Haig again apparently did not insist. This ‘hands-off approach was all the more curious in that Haig did not apparently fully trust Gough, since after one significant meeting on Passchendaele, Haig ‘clearly hinted that whatever Gough said should be taken with more than a grain of salt.’ This was a curious method of command in war, especially with a volatile, intolerant and unreceptive subordinate such as Gough. In fact, the whole decisionmaking process before Passchendaele was fatally flawed, with Gough being afraid to confront Haig over the plan, and at the same time an atmosphere of ‘terror’ operating in Gough’s own army, so that ‘none of his subordinates dared to tell him [Gough] the truth’.8 However, Haig was now stuck with a stalled offensive and a not very capable commander. The solution was to bring in Plumer and his Second Army, and gradually phase out Gough, which occurred towards the end of August. Yet what were the aims of the Passchendaele campaign now to be?

Originally, the Passchendaele offensive was supposed to aim for Roulers and the coast (Ostend), but this was clearly no longer obtainable. Instead the campaign now wavered between wearing out the enemy in preparation for a future decisive offensive—and capturing the Passchendaele Ridge and the village of Passchendaele as ends in themselves. Before the offensive began, the wearing-out option seemed feasible. Charteris had forecast that the German 1918 class of recruits had all been called up, and that the 1919 class of 450,000 men would start to appear in July 1917 and would be finished by about October, ‘provided fighting is severe’. There was the expectation that German casualties of 190,000 in July, rising to 200,000 per month until October, would leave Germany with only 1,000 men available in depots by October. In fact, in mid- to late August, Haig remained very confident, telling Major General Clive on 17 August that he was ‘certain that by the end of September we shall win the battle, if we go on hard’, and then at the end of August scornfully remarking that the new German defence in depth system, which utilized shell holes rather than trenches as protection for the forward zone, was ‘simply the refuge of the destitute’. Haig was confident, therefore, of continuing to execute the original plan, which included the Fourth Army landing on the coast, but which would ultimately lead to his traditional concept of drawing in and using up the German reserves, and then launching ‘the decisive attack’, as he told the CIGS, Robertson, in late August.9 In fact the ‘decisive offensive’ did take place on 20 September 1917, and again on 12 and 26 October 1917, although without the results anticipated. Yet despite the image of mud and blood and inept leadership that the battle of Passchendaele evokes, it is well to remember that in September and October 1917, the BEF was successfully employing an unprecedented volume of artillery fire, as well as other forms of technology against the German army (on 24 August 1917, Charteris estimated that the BEF was using 5,496 guns against 2,557 German guns), and from the point of view of an involved but dispassionate commander such as Maxse (GOC XVIII Corps), the BEF was winning the battle. For example, Maxse reported that his corps’ attack on 20 September 1917, using gas, tanks and a heavy creeping barrage, resulted in a gain of over a thousand yards, and great numbers of Germans killed and wounded. Maxse wrote that this proved ‘Haig was right and the croakers were wrong again as usual’. Then on 4 October 1917, Maxse wrote of a brilliant victory, with his corps gaining all objectives. On the other hand, there were certainly disastrous and bloody failures, as on 9 October 1917, when Lawrence’s 66 Division arrived late at the starting line, because of the swamps. The troops were taking 12 hours to cover 2 1/2 miles, and they were therefore one hour behind the barrage, and so suffered 6,000 casualties.10

As a means of attempting to come to some conclusions about the wearing-out option, casualty figures, however unpleasant, might provide some direction, although these figures are notoriously unreliable. One historian, using official figures, advances the estimate of 448,614 BEF casualties for the period of Passchendaele as against 270,170 German casualties. More recently another historian sees 200,000 German casualties, as against 250,000 British; and very recently a third historian includes contemporary figures for the whole of 1917, which result in estimates of 822,000 BEF casualties, and roughly 1,000,000 for the German army. Although accuracy may be impossible, it seems that a reasonably close evaluation was that of the British official historian Edmonds, who estimated 271,031 BEF Passchendaele casualties, and 75,681 for Cambrai. It is at least possible that German casualties for the period July to December 1917 might have approached BEF casualty figures more closely than is generally acknowledged, except by Edmonds.11 If so, the bloody strategy of traditional wearing-out operations at Passchendaele may have given encouragement to some commanders such as Maxse, even if there were other, less costly options available to GHQ, such as Messines-type operations, or the future tank assault at Cambrai.

However, as the autumn of 1917 waned, Haig appeared to become less interested in wearing-out as a strategy, and instead became preoccupied with obtaining the Passchendaele Ridge and the village of Passchendaele as aims in themselves. As was reportedly said at GHQ: ‘When we get the Ridge, we’ve won the war’, while Brigadier General Tudor, commanding the artillery of 9 Division, wrote in his diary in late October 1917, that Haig was determined to capture the Passchendaele Ridge and that all else was forgotten.12 The ridge and the village of Passchendaele had become symbolic to Haig, who hated to change his objectives. Equally important, however, was the fact that he believed only in Flanders could decisive results be obtained, and indeed only in Flanders could the war be won.13 Yet in discussing the capture of the village of Passchendaele, both Haig and Charteris could point only to its tactical significance, and both stressed that its capture had required only 700 casualties, as though this itself was a justification for the attack. However, a memo by Haig in mid-October 1917 points to another important reason for capturing the village and the ridge—it was that ‘we shall have excellent artillery positions and complete cover behind our starting line’. In other words, the ridge was primarily useful as a jumping-off place for the next BEF offensive in 1918! Clearly, there was no other importance to the place, and indeed the strategic aims of the Passchendaele campaign, apart from wearing out the enemy, had long since disappeared in the slow progress of August and September 1917. In fact, a conversation between Haig and his liaison officer with the French, Major General Clive, in late September 1917, revealed a dichotomy in Haig’s thinking. Haig told Clive that he believed the Germans would sue for peace over the winter, but that he hoped peace would ‘not come’ because Germany could be finished off next year. This was because Haig did not want peace to arrive before the German army had been cleared from French and Belgian soil. Nevertheless, Haig’s comment to Clive implied that he did not want the wearing-out option to succeed in 1917, which was presumably a major justification for continuing Passchendaele. But then Haig went on to say that Germany ‘has lost all the high ground at Verdun, Morouvillers, Chemin des Dames, Vimy, Messines, and probably Ypres; her troops will be in the water’. This would seem to indicate that Haig was thinking of Passchendaele as a simple battle for gaining high ground—a traditional nineteenth-century army attitude. It is probable that in the later stages of Passchendaele Haig did not clearly know what he wanted.14

Afterwards, Haig, Charteris and Davidson all attempted to argue that the Passchendaele offensive had been continued as late as November because of entreaties from General Pétain (French Commander-in-Chief), who pointed to the poor state of morale in the French army, which had earlier in 1917 suffered mutinies. However, it is crystal clear that Haig had always intended to continue the offensive in the hope that the Germans might crack; that already in mid-July Haig knew the French army was in better shape; and in fact far from protecting the French army, Haig was pressing hard for French offensives during the Passchendaele campaign. It may even be, according to Major General E.L.Spears, head of the British military mission to Paris in 1917, that it was Haig and not Pétain who thought the French army was capable only of minor operations! Finally, it is probably the case that Pétain would have preferred that the BEF take over more of the French line rather than continue the Passchendaele offensive.15

Ironically, it was less than a month after the end of the battle of Passchendaele in November 1917 that Haig was forced to tell his army commanders it was necessary to go on the defensive, move the guns back, and that there must be a defence in depth system, which ‘avoids the present salient caused by our occupation of Passchendaele’. In other words, the ridge may or may not have been useful as an offensive starting point, but it was a definite liability fo...