eBook - ePub

From Tsar To Soviets

Christopher Reed

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 336 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

From Tsar To Soviets

Christopher Reed

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Written from the perspective of the factory worker and peasant at the ground level, this study of Russia during the Revolution 1917-21 aims to shed light on the realities of living through and participating in these tumultuous events. The book is intended for undergraduate courses in history, Soviet studies, and politics.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es From Tsar To Soviets un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a From Tsar To Soviets de Christopher Reed en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de History y World History. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

PART ONE

Collapse of a society

CHAPTER ONE

Why was Russia revolutionary?

Revolutions are not caused by revolutionaries. In 1876, Petr Tkachev wrote that:

The preparation of a revolution is not the work of revolutionaries. That is the work of exploiters, capitalists, landowners, priests, police, officials, liberals, progressives and the like. Revolutionaries do not prepare, they make a revolution.1

Russia in the late nineteenth century provides a perfect example. The root causes of the revolution lay in the everyday working of Russian society, particularly its harsh and growing level of exploitation of peasants and workers and the rigid barriers erected against political change. The main losers from tsarism’s political immobility were a burgeoning and increasingly restless middle class and a more and more unsettled landed elite, which feared for its own security because tsarism appeared to be less and less capable of ensuring social stability. An examination of Russian society shows how assiduously tsarism was preparing its own downfall, not only because of what it did but, even more important, because of what it failed to do.

Rural crisis

The Russian Empire was overwhelmingly agricultural. The livelihood of the vast majority of its population was based on direct exploitation of the fruits of the land, the forests, the rivers and the coast. But that is about the only generalization one can make about it. The ways in which farming and husbandry were conducted varied enormously. In the Baltic region, German Protestant landowners ran modern capitalist estates. In the heartland of Russia, Ortho dox peasants tried to maintain an increasing population on ever more divided plots. In the east there were nomadic Buddhist tent-dwellers. There were tribes of animist hunters in the Siberian forests. In the Caucasus, mountain shepherds maintained traditional customs, including fierce, deep-rooted, feuds. Communities tracing themselves back to the ancient Greeks were still to be found on the shores of the Black Sea, site of Colchis, home of Jason and the Argonauts. There were extremely poor Jewish shtetls in Poland, relatively prosperous Hutterite German farmers on the Volga. Independent-minded cossacks of Russian origin defended their borderland villages in the area north of the Caucasus and the Black Sea against all-comers, particularly Turks. There were Islamic emirates in Central Asia, reindeer-breeding Lapps in northern Finland, Inuit eskimos in the Bering Straits region who crossed to and fro between Russia and its neighbour, the United States. The Russian Empire was a museum of human cultures, an anthropologists’ paradise. It had the cultural variety of the British Empire all wrapped into one, vast land mass which covered one-sixth of the land area of the globe and stretched through 180 degrees of longitude. St. Petersburg was as close to New York as it was to Vladivostok, and, until the early twentieth century, it took much less time to get to New York. East to west it stretched further than the distance between San Francisco and London or Paris and Tokyo.

Even within the relatively homogeneous Russian– and Ukrainian-speaking areas (where some 66 per cent of the population lived), fortunes varied enormously. In the southern provinces of New Russia, north of the Black Sea, the grain trade was booming, largely as a result of more efficient landowner production, though, by the early twentieth century, the peasant sector was also marketing a sizeable amount. Moving north, into the Black Earth zone, which stretched in a great crescent from the Rumanian border, through the Ukraine and Central Russia (passing south of Moscow) and on to the middle Volga and the Urals, the contrast was considerable. It was this area which was Russia’s arc of rural crisis. The fertility of the land had encouraged landowners to take as much of it as they could in the land settlement following the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. The basic principle of the settlement was that peasants should continue to farm land that had usually been theirs, though, to the disgust of the peasants, they were expected to pay the state for it. But in addition to the heavy mortgage repayment burden incurred, the arbitration of the land went against them. Peasants lost about 25 per cent of their land, a loss that was still keenly felt in 1917. In other areas, for instance in the western borderlands, they gained about the same amount. The explanation for this is that the government was hostile to Polish landowners and was happy to see them deprived of land as a punishment for their anti-Russian sympathies in the 1863 Polish rebellion. In the less fertile north, landowners could not make anything of the land without peasant labour and the settlement went more or less according to its proclaimed principles. Nonetheless, the realities remind us that behind countrywide averages, which suggest that peasants lost about 4 per cent of their land, lie enormous local differences.

In areas less affected by emancipation, such as the Baltic provinces where serfs were few, conditions were different again. Here there were large capitalist estates frequently owned and run by Germans or Swedes, with the local population employed as low-paid agricultural labourers, so there were relatively few peasants. In Siberia, the opposite was true, there were many peasant landholders, mostly migrants from European Russia, and very few noble landowners. This alarmed conservatives such as the Prime Minister, Stolypin, who commented on a trip to Siberia in 1910, that it was “an enormous, rudely democratic country which will soon throttle European Russia.”2

It was not, however, in Siberia that the revolution was brewing but in European Russia, especially the Black Earth zone. Between 1861 and 1905 the situation grew progressively worse for the peasants here. The main engine-room of the crisis was rising population which put increasing pressure on already inadequate plots. Between 1880 and the 1897 census the population of the Empire rose from 100 million to 130 million. By the time of the 1917 revolution it had risen further to 182 million.3

The consequences were severe. Russian agriculture, particularly among peasants, was practically untouched by modern methods. Traditional strip farming and three-field rotation were predominant. Horses and wooden ploughs were universal. Peasant livestock breeding and dairy farming were equally traditional. As a result, productivity barely kept pace with the increase in population. Migration could not counteract the full effects. The number of mouths to feed per hectare of land rose inexorably, particularly in the Central Black Earth region. When one also takes into account the rising tax burden and the fact that, despite increasing internal demand, grain prices were falling in response to international market conditions, the plight of the peasantry in the worst affected areas was visibly deteriorating on all fronts. In 1891–2 the fragile subsistence economy broke down in the middle Volga region and there was a great famine which claimed 400,000 victims.

The fact that, even during the famine, grain was plentiful in other parts of Russia, reminds us, yet again, not to generalize too readily about a country of such contrasts and vastness. Even though some sectors were very badly off, there was economic growth and real incomes for many increased. Over the whole period 1861–1913 the overall economic growth rate is put at around 2.5 per cent. A recent meticulous study by Paul Gregory has made a slight upward revision of the figure for the period 1885–1913 to 3.3 per cent instead of the previously accepted 2.5–3 per cent. Given a population increase of about 1.6 per cent per year, there was a slow growth in per capita incomes. Gregory’s picture has been forcefully backed up by Steven Hoch who has argued that the crisis of “overpopulation” has been exaggerated.4 However, one still has to account for two peasant revolutions.

Less is known about exactly how the growing wealth was distributed, a key factor from the point of view of explaining the revolution. Clearly, the most prominent feature of distribution in rural areas was extreme inequality. The landowners were a race apart from the peasants. Social mixing was infrequent, intermarriage almost unknown. Apparently mitigating factors like paternalism might often be seen simply as intrusion by the master into the peasants’ own lives. Sexual relations between landowners such as Bashkirev and attractive peasant women can also hardly be seen as a factor diminishing the social barriers. Indeed, the resentments aroused by such relations no doubt fuelled antagonisms, particularly on the part of rival peasant suitors, the women’s husbands or their families whose powerlessness would be emphasized in the face of such a situation. There is no evidence of comparable relations between peasant men and women of the landowning class.

Though overwhelmingly traditional the Russian countryside was not unchanging. As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth the pressures of modernization began to make themselves felt. Industrial recruiters came round more frequently looking for labourers for the factories. They often returned to the places they knew and particular districts became noted for particular trades—Kaluga produced brickmakers, Vladimir produced carpenters—and they tended to recruit by groups so local links between individuals often persisted into the city. An increasing number of girls left the rural areas to take up domestic positions in towns and cities in the households of the new bourgeoisie, others found a place in the service industries working in the expanding retail services trade. Some migrants would drift down into the world of petty criminals and prostitutes focused on, in Moscow for example, the notorious Khitrov market, near the Kremlin, where the visitor could expect to witness brawls and scuffles and was well advised to keep a tight hold on her or his purse.

Change did not come solely through those who left the village. In the 1860s local councils known as zemstva had been set up in many areas. Among other things they provided rudimentary health care and education, agricultural advice for the peasants and oversaw the development of an elementary infrastructure—maintaining roads, constructing bridges, damming rivers and the like. Such activities brought a leaven of intellectuals into rural areas as engineers, doctors and teachers and attracted, in particular, idealistic young men and women who were smitten with the intelligentsia yearning to “serve the people”, in this case by what were known as “small deeds” rather than total revolutionary transformation. By 1905, a substantial group of rural intellectuals, particularly schoolteachers, had become increasingly trusted by the peasants and, conversely, mistrusted by the landowners.5 Literacy began to trickle down into the countryside, widening access to broader cultural horizons.6 Not all areas were equally affected, some remaining hardly changed at all, but in some areas new ideas and new challenges were coming to the fore. Migration turned hundreds of thousands of peasants into Siberian settlers. Young people with independent sources of income began to challenge the authority of parents and village. Tolstoyan tracts encouraged many to de nounce the state, especially after Bloody Sunday in 1905.7 In a few cases, more common in town than country, scientific ideas, particularly Darwinism, began to filter down to the narod and challenge traditional religious beliefs. While these were, as yet, very limited processes, they were signs of the direction in which the peasant community was slowly evolving.8

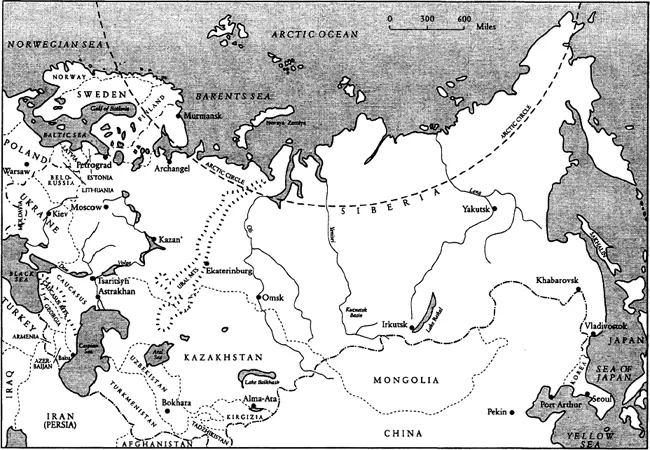

The Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR) in 1921.

Although landowners constituted a privileged minority they did, none the less, have problems of their own. In the first place, there was considerable inequality among landowners themselves. The landowning class itself formed a miniature stratified pyramid at the top of the national one. The apex was a small group of super-rich and super-privileged families. The Romanovs, the royal family, were at the very top. Their personal holdings were immeasurable. The tiny group of dominant families were a group apart. They were highly westernized in dress and customs and the court followed western European royal protocol adapted from French and German models by the leading force in westernizing the elite, Peter the Great, and his successors. They tended to speak western languages in preference to Russian. French was the most frequently used though Nicholas II wrote to his German-born wife Alexandra in English.

The dynasty and the families grouped around it were the rulers of Russia in every respect. They had oceans of wealth and immense institutional power and privileges. In a real sense, right to the very end, governing Russia was the Romanov family business. All their advisers at court came from within the charmed circle of family members and the tiny elite of leading families. The top army leadership came largely from their ranks, their dominance being particularly overwhelming in the politically vital guards regiments that were the prop of dynastic power. Even the February revolution had aspects of a traditional army-based coup d’état, intended to change one Romanov tsar for another.

The broad domination of society by a tiny traditional caste was completely inappropriate to modern conditions. This began to change slowly in the nineteenth century. Competence, rather than high birth, became an increasingly important prerequisite for government or military office but foot dragging meant that the elite continued to dominate key decision-making right to the end. This added enormously to the frustrations and tensions in Russian society and politics. Here, as much as anywhere, Tkachev’s analysis of the roots of revolution was being borne out.

The dominance of the major aristocratic families was untouched by the processes going on beneath them. They resisted social mingling and intermarriage with Russia’s growing office-holding nobility and were as remote from most of them as they were from the innumerable country squires and small-scale local gentry who populate many nineteenth-century Russian novels and stories. However, noble rank did not, in itself, guarantee elite status. Some impoverished noble landowners with small plots lived alongside and indistinguishably from their peasants. The flop-houses of Moscow had their share of fallen noblemen. Only nobility combined with substantial landownership or important office holding qualified a person for the elite.

It should also be remembered that the gentry class was itself undergoing something of a decline after the emancipation of the serfs. The number of landowners was falling. In 1861 there had been around 128,000 families who held land. In 1877 there were 115,000. By 1905 the number had fallen to 107,000.9 The reasons for this seem to lie in the difficulties that many landowners were experiencing in adapting to post-emancipation conditions. Now that their relations with peasants involved money rather than labour service the gentry were having to sink or swim in an increasingly market-oriented society. Many were finding it difficult. They were often underfinanced and, in any case, if money came their way they might well fall victim to the Russian vice of squandering it either at the card table or on spending sprees. Even attempts by the state to prop up the gentry by establishing a Nobles’ Land Bank in 1885, which, until 1894, loaned them money at lower rates than those offered by the Peasants’ Land Bank set up in 1883, could not arrest the decline. More and more of their land was mortgaged and the class as a whole was in ever deepening difficulties.

Important structural changes should not, however, blind us to the fact that not all the landowners were losers. As is normal with the type of capitalist, market processes that were developing in Russia after emancipation, the misery of many was the gain of a few and the gentry was no exception. Some, usually larger, landowners were able to consolidate and expand as many smaller ones were forced into selling the last of their property, offering rich pickings for local entrepreneurs, sometimes of peasant background, who were able to buy them out.

Industrial innovation

In many cases, the profits that the more successful landowners and entrepreneurs were investing in land had come from the expanding, modern, industrial sectors of the Russian economy. The leading sector in Russian industrialization was, as in the United States, the development of a railway network. Between the Crimean war and 1885 the network grew from 1360 to 27, 000 km. By 1900 there were 48,000 km and by 1914 77,000 km of track. Growth on such a scale opened up demand for iron, steel, wood, coal and oil to provide rails, locomotives, rolling stock and other equipment. In addition, many new skills were required from engine driving and signalling to timetabling and financial management. Peasants and sons of clerks had to be turned into skilled manual and intellectual workers by tens of thousands. There were also very important economic, political and cultural effects. The existence of a rail network broke down local economic isolation and drew larger and larger areas of the country into the national and, ultimately, the international economy. It also increased personal mobility and made migration and resettlement easier.

Alongside railways, the next most important sources of demand for industrial products were agriculture and the military. They needed machines (such as steam tractors for the former, artillery and warships for the latter) and chemicals (for instance, fertilisers and explosives respectively). By comparison, consumer goods showed less strong growth though there was a large textile industry based in Moscow and the Central Industrial Region and here, too, military orders were important. Much consumer demand was met by imports, particularly of luxury goods for the elite, and, sometimes, by foreign investment.

Though there is some argument about whether direct intervention was as important as had once been thought, no one seriously doubts that the state played a major role in Russian industrialization. Given the fact that the state attempted to dominate all aspects of Russian life it considered to be important, it is not surprising that it should have intervened here, too. There is, however, considerable dispute about its impact. Critics of state intervention have focused on the “inefficiency” factor. For the most dogmatic of them, all state intervention is harmful to the maximization of economic growth. However, real life is about more than high growth indices. Policies reflect dominant political interests not academic calculations of maximum benefit. In the real world it is hard to see what alternative there was. A key aspect of the whole process was the state’s desire to keep afloat nationally and internationally, which required more military power. This, in turn, required better communications and a higher level of science and technology. It also required funds. The fact that it was successive ministers of finance who were most actively involved points to the issue of raising revenue. Given the deprived and potentially unstable state of much of the peasantry, particularly in 1891–2 when Sergei Witte came to office as Minister of Finance, and the political unacceptability of taxing those who really had the money, the finance ministry had a problem. How could money be raised least painfully? The promotion of healthier new sectors of the economy offered a solution. Economic growth would provide much needed new funds.

A number of important features of industrialization, some obvious, some less so, help us to understand why Russia was pregnant with revolution. First of all, although Witte was an enthusiastic promoter of industrialization he did not speak for all the powerful groups in the Russian state. There was considerable opposition to his policy from those whose interests were damaged by it. Particularly important in this respect were some landowners whose imported goods, whether agricultural machinery or French wine, cost more as a result of tariffs. In fact, protection meant that high prices had to be paid for a whole range of goods, even those of Russian manufacture. In addition conservatives and reactionaries, who were legion in the corridors of aristocratic power, were fear...