![]()

Chapter 1

An Introduction to 3D: Recreating the World Inside Your Computer, or Not

You may be under the impression that working in 3D is an attempt to create the real world inside of your computer. It’s a tempting and logical thought—the world itself is 3D. It consists of objects that have a certain form, the surfaces of which have properties that make them appear a certain way, and of light that allows us to see the whole thing. We can create form, surface, and light inside of a computer, so wouldn’t the best approach just be to make everything inside the computer as close to the way it is in the real world and be done with it?

It turns out the answer is no—accurately simulating the world is not the best approach. That way madness lies.

We all live in the world. We know what it looks, smells, sounds, and feels like. More importantly though, we know what it looks like when carefully lit and shot through a lens by a skilled photographer. It is through two-dimensional (2D) images, either still or animated, that people will experience our 3D work, and this is the target we should be working toward. It turns out that this makes our job as a 3D artist both easier and harder than the job of someone who is mistakenly attempting to simulate the world. It’s easier because, well, the world is stupifyingly large and deceptively complex. It’s harder because there are considerations other than concrete sensory input (i.e., “A tree is shaped like this, feels that, and acts thusly”), and considerations like what is and is not seen in the final image, and at what level of detail: how it all goes together; how it demonstrates what you are trying to say; composition; art, even.

To be good at 3D creation, you will need to develop a facility for carefully observing the world around you, extracting those elements that will best contribute to your image and leaving the rest out. You will be creating a simulation of the real world that is specifically targeted at producing a final image—a unique virtual mini-world of which the sole purpose for existence is to create the illusion of reality in 2D that we experience when looking at a picture or watching a movie.

Let’s take a look at the different elements of a real scene that we will need to analyze and rebuild in order to achieve this.

Form

Everything that we see has a form—a physical structure. We know what these forms are: how a lion is shaped, what it looks like when pudding falls on the floor, the essence of a chair.

The essence of a chair?

Well, what is a chair, anyway? There are thousands of different kinds of chairs, but when we see one, we know it’s a chair. That’s because although the details differ, the form generally remains the same: a place to rest your back side, some means of support (usually legs, but it doesn’t have to be), and a back. If there’s no back, it’s a stool. And so when we see an overstuffed recliner, a swivel chair attached to a table in a fast food place, or just a basic dining room Queen Anne–style chair, our brain identifies the form and tells us “chair.”

It is form that lets us know what things are. In the real world, form is made from matter. Yes, that’s “matter,” as in solid/liquid/gas from science. I know that no one said there would be science here, but there is, as well as math—get used to it.

A lion’s form is made up of organs, bone, muscle, skin, and fur. Pudding is made from milk, gelatin, and, hopefully, chocolate. A chair’s form is constructed of any number of things, including wood, metal, and plastic. However, none of the insides really matter to our perception of the form. In general, we only see the outer surface, and that is enough for us to properly identify things.

This is the first place that we decide as 3D artists that we will not simulate the world as it is, but as we would see it through a lens. With a few exceptions, a camera only sees the outside surfaces of objects, so that is all that we need to worry about. If we want to create images of forms (“pictures of stuff” for the layman) we can temporarily forget about what things are made of and just focus on the shape of their surface.

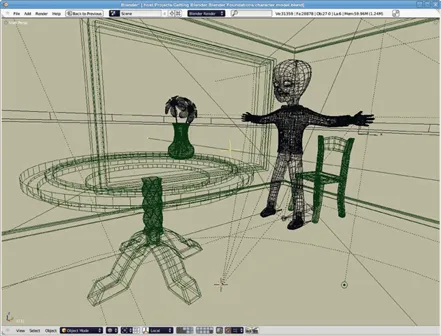

In 3D, surfaces are built from polygons, specifically triangles and quadrangles in Blender’s case (Figure 1.1). Usually, these polygons are built from vertices, edges, and faces (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 A scene created from polygons.

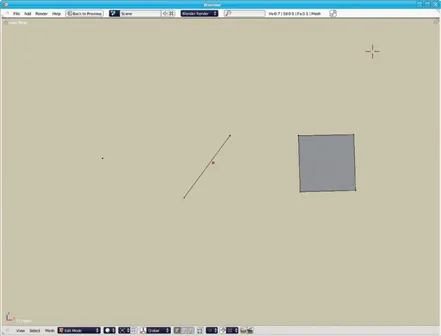

Figure 1.2 Vertex, edge, and face.

These polygons are created and linked together in clever (or not-so-clever) ways until the whole surface of a form is constructed. This construction is called a model. When making models in 3D, it is important to keep in mind how their form will be shown in the final image. If the image of the object will be very small, perhaps because it is far in the distance or just a tiny detail like a flea or a grain of sugar, the model can be very simple (Figure 1.3). There would be no need to create a model of a building in exhaustive detail if it appeared only one-quarter inch high on a distant hillside in the final image.

Figure 1.3 A landscape with a building in the distance.

(Photograph by alexanderwar12/Al, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic.)

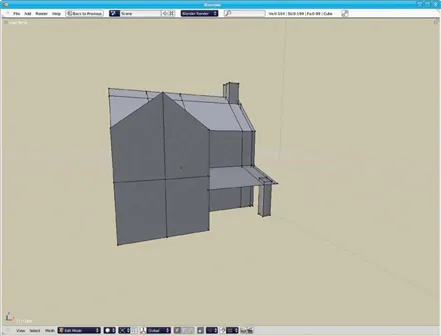

We know what the form of such a building is in the real world. It has a roof, a chimney, windows with trim, maybe a spigot for a hose, and many other details. However, when we look at the 2D image with a critical eye, we can see that for our purposes, the building is little more than a box with a triangular top. If we were trying to reproduce this image in 3D, we would save ourselves a lot of trouble by modeling a simple box with a triangular top (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 A basic model of a building for use in the distance.

Obviously, if this same building were the main subject of the image, shown close up, its form in the image would be drastically different, and we would model it differently (Figure 1.5). In fact, depending on the image we are trying to achieve, we might only create a model of a portion of the building. If the image consisted of a close-up shot of the exterior of the building, we might choose to only model that part of the building that shows on camera.

Figure 1.5 The project scene—the forms are obvious.

In 3D, models that are made of polygons are our forms. They tell us what we are looking at. As a final example, take a look at the scene project for this book, without any texturing or lighting. It is only the forms, yet we know immediately what everything is. Clearly, though, none of this stuff is real, could be mistaken for real, or is even believable. That’s because believability comes not from form, but from surfacing and lighting.

Surfacing

Surfacing refers to the way that surfaces look. Once again, we can examine the real world to learn a few things. We know what wood looks like. However, it looks different when it’s part of a tree, freshly cut, or stained and finished in a piece of furniture. Each of these surfaces have different visual properties. A tree is rough—the bark is generally a brownish gray, rough, occasionally covered with moss or lichen. Cut wood is often light (excepting things like walnut, of course) with a pattern of concentric circles. It is generally smooth, although if you look closely you can see a pattern of grain. Finished wood that is part of a piece of furniture can be many colors; for example, it can be extremely smooth and highly reflective, in the case of a grand piano.

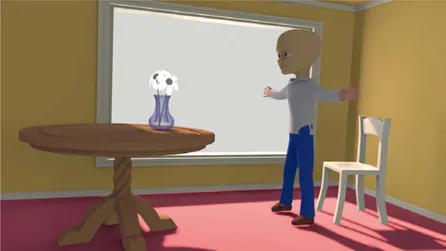

So, while models tell us what forms we are looking at, surfacing gives us the additional clues we need to understand what the forms are made of (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6 The project scene with surfacing added, and mixed about.

Once surfacing has been added, the image becomes much more believable. In fact, surfacing gives us so much information that if we mix it up, the scene remains believable in a general sense, but becomes strange. It plays with our expectations of what we should be seeing.

In Blender, an object’s surfacing is described by two sets of properties: materials and textures. Materials involve the basic visual properties of the surface, without texturing (Figure 1.7). How does light react when it strikes the surface? Does the surface emit its own light? Is it rough or smooth? Is it reflective? Is it transparent? Does it act like milk or skin, taking a little bit of light inside itself, scattering it around, then letting it back out?

Figure 1.7 The project scene with no texturing.

With the basic materials in place, the objects in the scene take on a certain aspect of believability. Even though they don’t look real, they at least look like physical objects.

Material properties deal with a number of areas:

• Color: The basic, overall color of the surface in white light.

• Shading: The way that light affects a surface. How much light does a surface absorb or reflect? How do the angle of the incoming light and the viewing angle affect what it looks like? Different shading models are available to give you a better chance at mimicking certain effects seen in the real world.

• Transparency: Whether or not an object’s surfaces are transparent. Simple transparency, based on something called Alpha (Z-transparency in Blender) is quick to render. Another method of calculating transparency, called ray tracing, takes longer to render but is more realistic and able to simulate effects like refraction.

• Reflection: Is the surface mirrorlike?

• Subsurface scattering: Certain real-world materials like skin, jade, or the flesh of a potato exhibit this property, often abbreviated as SSS. Light enters the material, scatters around, possibly changes color a bit, then exits. When you hold a flashlight against your fingers in the dark, you see subsurface scattering.

While these material properties affect an object’s overall reaction to light, textures help to define the way that those properties vary across the surface. Textures can be photo mapped onto a surface, generate bumps on a surface, or cause transparency to fade in and out, among other things. A careful observation of objects in the real world will help you to determine which combinations of material settings and textures will produce the most believable results.

Light

The final ingredient in your still images is light. In the real world, light appears to be easy. You have the sun and the sky. If you need more light than that, you flip a switch. That’s it!

Of course, good photographers know that it’s not that simple. Even if they are shooting outside, they carefully monit...