![]()

Part 1

Roots

Introduction

Many architects are fond of saying, in jest of course, that theirs is the second oldest profession in history. There might be some truth to this since building shelters is one of the earliest forms of organized human endeavors. Since urban design is functionally, if not etymologically, linked to architecture, and as urban design endeavors can be traced even in ancient times – from the Vastu Shilpa principles that dictated the design of ideal cities in India to the Chinese efforts over a millenium to tweak the ideal city form – it poses a problem for us to define the appropriate time frame for tracing the “roots” of urban design. Clearly the scope of this endeavor did not call for a comprehensive history of city and urban design. After all, there are already many authoritative works on this subject. In consultation with our contributors, then, we chose to focus on the most recent history of what can be considered contemporary urban design, beginning in the earlier half of the previous century. The chapters included in this section reflect this time period.

The opening chapter by Eugenie Birch includes a comprehensive review of the important projects, protagonists, and promoters of contemporary urban design, including its organized movements and institutional patronage. In framing this review the author chooses to bookend the two important movements of our time – CIAM (the French acronym of the International Congress of Modern Architecture) and CNU (Congress for New Urbanism) – which have shaped much of the thinking and practice of large scale urban design. This intriguing history is both about idealism and pragmatism, about individual and organized efforts, and about important projects and paradigms of urban design, much of it in the context of the socio-economic and political history of the US urban development during this period.

The following chapter by Robert Fishman frames the history of ideas in urban design in a similar time frame. The author defines the history of ideas as one of two competing paradigms – which he calls “the open” and “the enclosed,” referring to the earlier modernist paradigm of city design shaped by Le Corbusier’s idea of “tower in the park” on the one hand, and the yearning for a more compact urbanism of spaces defined by building façades and enclosed squares, characteristic of earlier cities. The author suggests that there might be a shift in the thinking about these two paradigms, as the concerns for sustainability, walkability, and mixed use urbanism continue to dominate public policy.

Finally, the third chapter in this section by Danilo Palazzo focuses on the history of the pedagogical tradition in contemporary urban design. The author carefully traces the institutional settings, innovations, and disciplinary influences that have shaped the training of urban designers in the US. In reporting this history, the author identifies key figures and programs which were influential in defining the professional training of urban designers.

These first three chapters of the Companion set the chronological stage and historical background of the chapters appearing in the following sections.

![]()

1

From CIAM to CNU

The roots and thinkers of modern urban design

Eugénie L. Birch

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, rapid urbanization in the western world stimulated dramatic responses in many disciplines, ranging from the social sciences to the design professions. Independently, they sought to understand and address urban issues. Sociologists, for example, wrote about deep differences in behavior among city and country residents, identified urban alienation, and offered remedies to promote community in cities (Tonnies 1887; Park and Burgess 1925; Perry 1929; Wirth 1938). Architects, city planners and landscape architects framed their professional practice around solving problems caused by population congestion (Le Corbusier 1924; Birch and Silver 2009). Their debates surrounded architectural style (neo-classical vs. modern), ideal settlement patterns (centralization vs. decentralization) and means to improve the internal organization of cities through better open space, land use, housing and circulation.

Among designers, these varied concerns led to the formation of a new field, variously labeled “der stadtebau (German)” “urbanisme (French),” “civic art,’’ “civic design,” “city design,” and “urban design.”1 Now commonly known as urban design, its development spanned more than a hundred years, fed by synergistic relationships among five leadership groups (Precursors, Founders, Pioneers, Developers and Later Evolvers), who shaped its content and influence (see Table 1.1) In tracing the roots of modern urban design, this chapter will focus on the Founders, Pioneers and Developers, who were active from the 1920s through the 1970s, cognizant that the field’s history is longer and broader but arguing that work in these years was formative.

Modern urban design emerged in the late 1920s as a loose organization of European and American architects and city planners, or Founders, who declared that they could solve ever-worsening urban problems (defined as unhealthy housing, inefficient land use and inadequate transportation) through enlightened city-building. Their highly conceptual work, mainly took the form of writing and unrealized projects. The Pioneers (architects, landscape architects, city planners and urban-focused writers/scholars) expanded the field in the 1930s and 1940s with contributions encompassing writing, a few projects and educational experiments. Developers emerged in the 1940s as European reconstruction and US urban renewal programs gave impetus to the growing movement. Drawn from the same design communities but armed with new social science research, they wrote for scholarly and popular audiences, built projects and created advanced degree programs, thus promulgating the field in its solid theoretical and practical aspects.

Table 1.1 From CIAM to CNU: The roots of urban design

Note: The dates proffered are rough guidelines as many participants were active in more than one era.

The Founders

The idea of building a modern, rationally ordered city captured the imaginations of many designers, mainly architects in the early twentieth century; Swiss architect Le Corbusier is one example; the German-born architect Walter Gropius is another. Their fascination with the use of simple, mass-produced industrial products for housing soon led to an infatuation with the skyscraper, viewed as an emblem of its times, much like the cathedral in the Middle Ages. They sited low-lot coverage high-rises (often labeled “towers in the park”) arguing that this building form could improve urban life by capturing the density required for city vitality while relieving ground-level congestion. It was a short step from designing such buildings to arranging them in geometric patterns in whole cites. Here, the designers called for replacing the obsolete industrial city with a modern one marked by land uses separated by function, superblocks of high-density districts (residential, downtown) and ample recreational areas knit together by modern highways. To display these ideas, Le Corbusier offered a succession of unrealized projects (La ville contemporaine [1922], Voisin Plan [1925] and La ville radieuse [1935]) and writing (Urbanisme [1924]).

In 1928, Le Corbusier and other likeminded designers founded the influential Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) that held annual congresses from 1928 to 1956 (with some interruption for World War II) in Europe and publicized their beliefs and work widely. Starting as a small group of two dozen at its initial meeting in La Sarraz, Switzerland, CIAM would grow rapidly, attracting more than 3,000 attendees to its annual congresses by the early 1950s (Pedret 2001: 151). Left-leaning and inspired by social justice as well as modern architecture, CIAM first focused on slums but soon took on the city. Their fourth congress, entitled “The Functional City,” demonstrated this shift. Originally scheduled for Moscow to display the possibilities of modern architecture in a socialist setting, the organizers moved it elsewhere when the Soviets rejected Le Corbusier’s entry to the Palace of the Soviets competition, concluding that “the avantgarde (sic) had no place in Stalin’s Russia” (Giedion 1966: 698).

CIAM IV took place in summer 1933, on board the SS Patris II sailing from Marseilles to Athens and back and in a hotel in Athens. For fourteen days, the participants engaged in a comparative urban planning exercise, looking at thirty-three cities according to standards based on Patrick Geddes-recommended analytical surveys and codified by the Dutch urban planner Cornilis van Eesteren. They also had non-stop committee meetings to distill their work into a brand of modern city planning that encompassed four simple functional areas: housing, work, recreation and transportation (Geddes 1915; Somer 2007; Mumford 2000). Within this rubric, they promoted relieving congestion through slum clearance and rebuilding along the lines of Corbusier’s “towers-in-the park” concept. Their doctrine contrasted directly with the competing British-based garden city vision that advocated decentralized, low-density satellite cities as a means of improving urban life.

Due to internal dissension about certain details, CIAM did not formally publish the CIAM IV proceedings as planned, but in 1941 Le Corbusier boiled down the results into a manifesto and issued it under the CIAM name as La Charte d’Athènes (1943). He captured the pre-World War II modernist urban design principles in 95 bullets, e.g.

1 The city is only a part of the economic, social and political entity which constitutes the region … 9. The population density is too great in the historic, central districts of cities … 30. Open spaces are generally insufficient … 69. The demolition of slums surrounding historic monuments provides an opportunity to create new open spaces … town planning is a science based on three dimensions, not two. This introduces the element of height which offers the possibility of freeing spaces for modern traffic circulation and for recreational purposes. …. (Tyrwhitt 1933)

At about the same time, Spanish architect and CIAM-member Josep Lluís Sert produced a longer English version, Can Our Cities Survive? An ABC of Urban Problems, Their Analysis Their Solutions Based on the Problems Formulated by the CIAM (1942). Together, these works defined CIAM-led urban design.

Although CIAM was dominant in promoting city-building ideas in the twentieth century, it was not alone. Visionary illustrator Hugh Ferris shared Le Corbusier’s love of the skyscraper, producing dramatic images of its possibilities in Metropolis of Tomorrow (1929), while German architect Werner Hegemann and his American associate, Elbert Peets, documented the strength of urban cores, especially civic centers, in The American Vitruvius, The Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art (1922). Notably, Hegemann argued that civic art required gleaning knowledge from the social sciences, humanities and design (architecture, city planning, fine arts and landscape architecture).

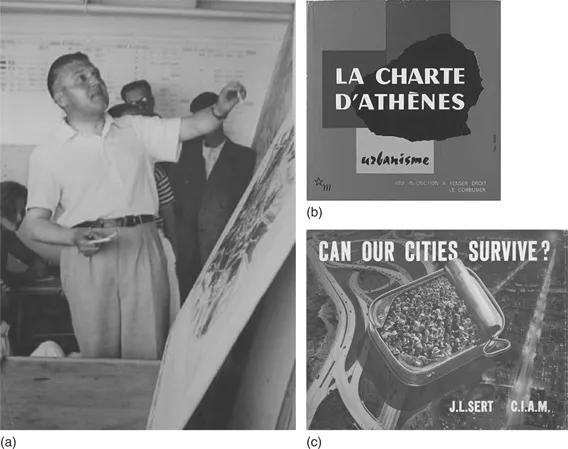

Figure 1.1 CIAM (1933) meeting and later publications.

Note: CIAM IV met in 1933 to discuss the “Functional City,” through comparative urban planning (a) whose proceedings were issued as the Athens Charter, which was not published until 1943 and then again in a second edition 1957. The cover (b) is from the second edition (Paris: Editions des Minuit). (c) A year earlier, Josep Lluis Sert had published through Harvard Press a longer version of the congress and its city planning views in Can Our Cities Survive?

Prior to publishing American Vitruvius, Hegemann had practiced in the United States, hiring a Beaux-Arts-trained architect, Joseph Hudnut, as an assistant in 1917. Hegemann returned to Germany in the 1920s but came back to the US in the 1930s, meeting up with Hudnut again, who, by this time, was Dean of Columbia University’s School of Architecture. As Dean, Hudnut sought to insert civic design into the curriculum and hired Hegemann and a rising landscape architect, Henry Wright, to teach the subject. In 1936, Harvard recruited Hudnut to be the founding Dean of the Graduate School of Design (GSD). There, he would aggressively pursue the idea of synthesizing the professions through civic design, hiring faculty who shared the vision and requiring all students to take a common introductory course (Pearlman 2008).

Meanwhile, decentralists were also active. Garden city proponents including Raymond Unwin, author of Nothing Gained by Overcrowding (1912) and Town Planning in Practice (seventh edition 1920) and designer (Letchworth Garden Suburb 1903–1920s), offered an alternative vision of civic design, one quickly adopted by leading American urbanist Lewis Mumford. He called for decanting the crowded metropolis into peripheral self-contained cities.2 But it was American planning practitioners, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and his student, John Nolen, both steeped in landscape principles at Harvard, who executed these theories in the United States, drawing on European precedents, especially English and German efforts in housing reform and zoning. For example, Nolen’s plans for model suburbs like Charlotte’s Myers Park and for complete towns like Mariemont, Ohio, Kistler, Pennsylvania and Venice, Florida were notable examples of the translation of garden city principles in the United States. He articulated the “American brand,” showing how to plan for places for relatively small populations (25,000 to 100,000) in self-contained satellite cities bounded by greenbelts, containing town centers, a range of housing choices, neighborhood-to-region park systems, buffered industrial sectors and hierarchical street arrangements (Nolen 1927). While practitioners like Nolen and Olmsted, Jr. were not directly involved with CIAM, their ideas fed the knowledge base of urban design, and in fact, would provide reference material for later expressions of urban design, especially new urbanism.

The Pioneers

While divisions among the Founders were present, opposing philosophies related to density and decentralization emerged more prominently among the many Pioneers who followed. While they built on the Founders’ thinking, especially the CIAM pronouncements, they also added new ideas. Further, some Pioneers worked independently but were conscious of the others and drew inspiration according to their inclination and needs. Author Clarence Perry, for example, devised the “neighborhood unit,” a physical/social arrangement centered on the grade school and its surrounding catchment area as a basic city-building block. Clarence Stein and Henry Wright adapted this idea at their Radburn New Jersey garden city experiment (1929).3 Some CIAM followers were cognizant but critical of the neighborhood unit (and of garden cities...