eBook - ePub

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Peter A Clayton, Martin Price

This is a test

- 192 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

Peter A Clayton, Martin Price

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Sets each of the seven wonders in their historical context, bringing together materials from ancient sources and the results of modern excavations to suggest why particular places and objects have been seen as the touchstone for human achievement.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World de Peter A Clayton, Martin Price en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Histoire y Histoire antique. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

THE GREAT PYRAMID

OF GIZA

THE PYRAMIDS of Egypt have always been listed from the beginning amongst the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, but it is actually the Great Pyramid at Giza that is the focus of attention and takes its place at the head of the list. It is the only one of the Seven Wonders that still stands in an almost complete and recognisable form; it is also the oldest. Built for the pharaoh Khufu (or Cheops, as the Greek historian Manetho calls him) of the Fourth Dynasty, about 2560 BC, the pyramid represents the high water mark of pyramid building in Old Kingdom Egypt.

The Greek priest/historian Manetho, who came from Sebennytus in the Delta of Egypt, wrote a history of Egypt during the reign of Ptolemy II (284–246 BC). In it he divided ancient Egyptian history into a series of thirty dynasties. These fell into three main sections – the Old Kingdom (First to Sixth Dynasties, c. 3100–2181 BC, although the first three dynasties are also referred to as the Archaic period); the Middle Kingdom (Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties, c. 2133–1786 BC), and the New Kingdom (Eighteenth to Twentieth Dynasties, c. 1567–1085 BC). These represented periods of central government stability (ma'at in ancient Egyptian, a goddess represented by the Feather of Truth who governed all things that the Egyptian relied upon – truth, stability, the never-changing cycle of life, etc.). In between these three major periods were times of instability with the breakdown of central government. They are known respectively as the First Intermediate Period (Seventh to Tenth Dynasties, c. 2181– c. 2133 BC), and the Second Intermediate Period (Thirteenth to Seventeenth Dynasties, c. 1786–1567 BC). It was during the latter period that Egypt first suffered domination by outside peoples, the Hyksos (the so-called ‘Shepherd Kings’) who came from the Syria/Palestine area and were finally expelled in the mid-sixteenth century BC by warlike princes of Thebes in Upper Egypt who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty and the New Kingdom. Egyptologists refer to the period after the Twentieth Dynasty either as the Third Intermediate Period or the Late Period (c. 1085–343 BC). This includes the Twenty-sixth or Saite Dynasty (664–525 BC), a period of renaissance of Egyptian art and architecture. The Twenty-seventh Dynasty (525–404 BC) had seen Egypt ruled by Persia with a resurgence in the Twenty-eighth to Thirtieth Dynasties. After the death of Nectanebo II, the last native pharaoh, in 343 BC Egypt was once again ruled by Persia and then, with the coming of Alexander the Great in 332 BC, by the Macedonian Greeks. They ruled as the Ptolemaic dynasty until the suicide of the last of the line, Cleopatra VII, in 30 BC when Egypt became a Roman province.

The building of pyramids is essentially an ancient Egyptian phenomenon although there are pyramidal structures elsewhere, notably in the New World but the latter served different functions, had a different shape and the earliest were built at least 1000 years after the last Egyptian royal pyramid. Cheops' pyramid (to use the generally better known Greek form of his name) is not an isolated phenomenon but the apogee of a long line of tomb development that culminates at Giza and which then deteriorates thereafter. The Pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties are sorry affairs and the last royal examples of the Eleventh and Twelfth Dynasties not much better. Subsequently the royal burials during the New Kingdom were made at the religious capital, Thebes (modern Luxor) in Upper Egypt. They were hidden in the Valley of the Kings on the west bank, a remote valley still under the guardianship of a pyramid, a natural one known as the ‘Lady of the Peak’, which rises high above the valley and is sacred to the goddess Meretseger, ‘she who loves silence’.

Pyramids are the very epitome of kingship in ancient Egypt but, although large royal tombs, they have a long line of antecedents that stretch back to the small royal tombs of the earliest dynasties. There is an architectural progression to be observed which culminates in the Great Pyramid. The royal tombs of the first two dynasties, c. 3100-c. 2686 BC, are still a matter of some debate amongst Egyptologists as to whether they are located at Abydos, a site in Upper Egypt sacred to Osiris, the god of the dead, or at Saqqara, the necropolis of Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt, which lies just south of modern Cairo. The problem lies in the fact that two tombs were prepared, one as the actual tomb and the other as a cenotaph. In this double provision the old title of pharaoh since the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under Menes (or Narmer) in c. 3100 BC was fulfilled: ‘King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Lord of the Two Lands’, and he had a burial place in each area. Due first to the ravages of the early tomb robbers and then of time, it has proved very difficult for the main excavators of these two sites, Sir Flinders Petrie and Professor W.B. Emery respectively, to settle the question finally. Often the only remaining inscribed evidence amongst the debris consists of clay wine-jar seals, the rest is of broken pottery and what the robbers discarded as useless. These ‘rejects’ give us but a glimpse of the splendid furniture of carved wood and ivory, beautifully studied animals such as lions and lionesses in ivory, coursing hounds, etc., which were used as gaming pieces, and the like that were placed in the rooms adjoining the main burial chamber.

Two different forms of monument are evident at Abydos and Saqqara. At Abydos the burial chamber and its attendant storerooms were dug underground and roofed with timber baulks buried beneath a low mound. At Saqqara similar provision was made but the superstructure of the tomb took the form of a ‘mastaba’ (so-called by the Arabs because it resembled the bench outside the door of native houses). This low, flat-topped structure had an ornamental façade around it; known as the ‘palace’ façade. It consisted of alternate pilasters and alcoves of mud brick forming an articulated wall. At Saqqara, Emery found the two kinds of superstructure together in the tomb of Queen Herneit, the tumulus pyramid directly over the burial with the surrounding ‘palace’ façade walls. He considered this to be a prototype for the later royal tomb, the Step Pyramid of King Zoser of the Third Dynasty (less than a mile away in the necropolis). For the nobility in the Old Kingdom the mastaba tomb became the standard type of burial but for the pharaoh it developed. Zoser, the third king of the Third Dynasty, c. 2670 BC, had his monument built at Saqqara by his vizier and architect Imhotep (who was deified in the Late Period as a god of medicine and architecture). Imhotep introduced an innovation: he built in stone, using small blocks, for the first time in history. Zoser's tomb, the Step Pyramid, began life as a normal mastaba but was enlarged three times, in reality becoming three mastabas placed one upon the other and culminating in a structure some 70m (204ft) high and having seven steps. This is the first pyramid, but it was not a true pyramid since the sides, the ‘steps’, were not filled in to produce a smooth outer surface. Zoser's successor, Sekhemkhet, had his tomb built nearby and, although unfinished, we know that it followed the same style. Huni, the last king of the Third Dynasty, c. 2615 BC, built his pyramid at Meydum, to the south of Saqqara. This was begun as a step pyramid but the steps were filled in to give a smooth outer casing. There seems to have been a problem with this since the pyramid suffered a collapse at some point that left it with its present curious, almost lighthouse (pharos), shape.

At the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty Sneferu, the first king, began building his tomb in what is the more accepted pyramid shape. In fact, he had two pyramids, both at Dahshur and about a mile apart. The earlier of the two is known as the Bent or Rhomboid Pyramid because it suddenly changes its angle from a slope of 54 degrees to 421/2 degrees. The late Professor Kurt Mendelssohn suggested that the pyramids at Meydum and Dahshur were built concurrently, not consecutively, and that there was a sudden disaster, a collapse, at Meydum, perhaps after a heavy downpour of rain. The architect working at Dahshur probably thought that the angle of the slope of the pyramid's outer face was a contributing factor and accordingly cut it at Dahshur to give the Bent Pyramid its shape. The other pyramid of Sneferu, the Northern Pyramid, a mile away, has an angle of 43 degrees 36 minutes, much shallower than its predecessors but one that is closer to the eventual accepted slope.

These then are the antecedents of Cheops' pyramid at Giza. Cheops was the son of Sneferu and must have been very familiar with the architectural as well as the logistical problems involved with his father's tomb. The pyramid shape itself was closely tied up with the worship of the sun-god Re of Heliopolis. It began as the stubby obelisk upon which the benu bird alighted in the creation myths and also represented the culmination of the sun's rays as they reached down to earth – a natural phenomenon that can still be observed in the right weather conditions. When Cheops began the construction of his pyramid at Giza he therefore had a religious background as well as a long evolution as guidance.

In 1974 Professor Mendelssohn published two interesting theories: one was that the Meydum pyramid collapse influenced the building changes evident at Dahshur; the other, closely allied with this, was that not all the pyramids in the Old Kingdom were built consecutively, i.e. one after the other as required by each pharaoh for his burial, but concurrently, i.e. more than one might be in process of building at the same time, which would explain Meydum and Dahshur. As a corollary to this he added a further observation – there are more pyramids extant in the Old Kingdom than there are known pharaohs. Some of the pyramids do not appear to have been used for a burial; for example, at Meydum the burial chamber is very small and also unfinished, and there is no trace of a sarcophagus ever having been in it. At Dahshur Sneferu could only have been buried in one of the two pyramids. Mendelssohn therefore put forward the radical suggestion that pyramid-building was not due solely to religious motivation but that it also had another function, to be a great national endeavour which thus gave cohesion to the growing state of Egypt. His suggestions, it must be admitted, have not found favour with all the Egyptological fraternity, but they did at least highlight a number of problems and should not be too lightly dismissed.

With Huni, the last king of the Third Dynasty, another innovation appears at Meydum connected with the pyramid. We see the beginnings of the ‘pyramid complex’, the pyramid being part of a set arrangement along with other buildings. (At Saqqara the Step Pyramid had been set within a large enclosure with associated dummy buildings.) The pyramid funerary complex consisted of four parts. It began with a Valley Temple built on the edge of the cultivation. Here the pharaoh's embalmed body would be brought across the Nile from the embalmers' quarters for burial. From the Valley Temple a long Causeway led up to the site of the pyramid. Initially the Causeway was used as a roadway to transport the huge blocks of stone brought by barge on the Nile flood to the Valley Temple site. When that aspect of the pyramid construction was complete the Causeway took on a religious connotation. Its sides were built up, decorated with sculpted scenes (as we can see in the reconstructed section of the Fifth Dynasty Causeway of the pharaoh Unas at Saqqara) and

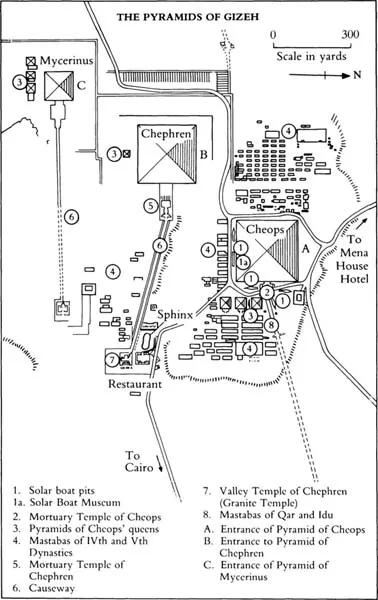

8 Site plan of the pyramid complex at Giza. (Courtesy of Swan Hellenic Ltd)

9 Seated statute of the Vizier Hemon, cousin of Cheops and chief-of-works for the Great Pyramid. Height 1.56m. (Pelizaeus Museum, Hildersheim, Germany)

roofed over with just a narrow slit left to admit some light. Up this enclosed route the pharaoh's body would be brought, safe from impious eyes, to the Mortuary or Pyramid Temple that was built at its end against the east face of the pyramid. From here, after the appropriate rituals, the mummy would be taken round the side of the pyramid to the entrance on the north face and thence into the interior to the burial chamber. At the Great Pyramid the Mortuary Temple still stands, but very much ruined, against the platform on the east face. The Causeway can be picked out on the surface but the Valley Temple has not been excavated and lies beneath the modern Arab village to the east on the edge of the cultivation.

Cheops chose a new site for his tomb, the edge of the Libyan desert on the plateau at Giza. He was to be followed here by at least two of his major successors in the Fourth Dynasty: Chephren (Khafra), and Mykerinus (Menkaura) (Figure 8). We believe that his architect, or more properly his chief-of-works, was his cousin the Vizier Hemon, whose seated statue was found in a tomb at Giza in the last century and is now in the Pelizaeus Museum,

10 Tiny ivory statuette of Cheops, seated holding the flail in his right hand and wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. His name is inscribed in a serekh on the side of the throne beside his right leg. Found at Abydos. (Cairo Museum)

Hildersheim, West Germany (Figure 9). It shows a powerfully built man, corpulent in the manner of Old Kingdom sculpture to show a person of position and eminence. Most statue representations tend to be rather idealised, showing the subject in the prime of life. With Hemon, the facial features have been damaged by tomb robbers who prised out the inlaid eyes that gave it a lifelike appearance. This effect was achieved by using obsidian and crystal as the pupils, white limestone for the irises and the whole set within a bronze surround.

Curiously, despite all the size and importance of the Great Pyramid, there is only one surviving complete representation of its builder Cheops. This is a tiny ivory statuette of the king found in 1903 by Petrie in the foundations of the Osiris temple at Abydos (Figure 10). The king is seen seated holding a flail in his right hand and wearing the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. On the front of the throne on which he sits is inscribed his name, enclosed in the royal serekh. Despite its diminutive size and the material, it is a portrait with strong characteristics. There are some superb portraits of the other builders at Giza, notably the seated diorite statue of Chephren and the series of slate triad plaques, as well as statues, of Mykerinus.

Before building work could commence it was necessary to prepare the site – it had to be made level and also the proposed sides had to be carefully oriented with the four cardinal points of the compass. The levelling was probably done by marking out the appropriate area with a series of four low mud walls. The encl...

Índice

Estilos de citas para The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

APA 6 Citation

Clayton, P., & Price, M. (2013). The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1607711/the-seven-wonders-of-the-ancient-world-pdf (Original work published 2013)

Chicago Citation

Clayton, Peter, and Martin Price. (2013) 2013. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1607711/the-seven-wonders-of-the-ancient-world-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Clayton, P. and Price, M. (2013) The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1607711/the-seven-wonders-of-the-ancient-world-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Clayton, Peter, and Martin Price. The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.