eBook - ePub

Theatre Sound

John A. Leonard

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 208 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Theatre Sound

John A. Leonard

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Theatre Sound includes a brief history of the use of sound in the theatre, discussions of musicals, sound effects, and the recording studio, and even an introduction to the physics and math of sound design. A bibliography and online reference section make this the new essential work for students of theatre and practicing sound designers.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Theatre Sound un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Theatre Sound de John A. Leonard en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas y Teatro. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Chapter 1

History of Theatre Sound

Almost all theatre productions involve sound; in its most basic form, it is the sound of the actor’s voice, and even the Ancient Greeks used a form of processing via masks to distort and project the voice of the performer.

In the main, however, sound in classical drama involved the imitation of natural sound by artificial means. Where no device existed to produce a sound, one was either invented by a resourceful craftsman, or the information was written into the text. Information about time of day, the weather, the seasons of the year and the location is given in the text of these plays, and the audience used their imagination to fill in the gaps. Shakespeare’s plays are full of location hints: ‘This is the Forest Of Arden …’; ‘What country, friend, is this? It is Illyria, my lady …’, and statements about the weather, surroundings and time of day: ‘This castle hath a pleasant seat …’; ‘How goes the night, boy?’; ‘The night has been unruly. Where we lay/Our Chimneys were blown down …’.

Chekov, Ibsen and Shaw all wrote complex sound effects into their plays, and the sound designers of the past hundred years were required to produce these by purely mechanical means. Much ingenuity went into the production of devices such as wind machines, rain boxes, thunder sheets and thunder runs to serve the demands of the play, and it is a sobering thought that it is only in the second half of the twentieth century that the complex system of recording and playing back sound and music that we are so familiar with has been available.

Ibsen demands an avalanche in When We Dead Awaken; Shaw requires a plane to crash offstage in Misalliance, and a full-scale Zeppelin raid in Heartbreak House. Both Journey’s End by R. C. Sherriff and The Ghost Train by Arnold Ridley require extremely complex sound effects plots. The instructions on how to recreate a First World War battle or to make the sound of a phantom steam engine may seem very funny to today’s sound designer, but just think of the ingenuity that went into designing those effects and into making them happen night after night. I believe that it must have been more satisfying than going to the effects library and pulling out a stock steamtrain recording.

The point here is that playwrights would use stage directions for effects only when they thought the play required them. We have no way of knowing whether Shakespeare would have included sound effects of Italian crickets for the balcony scene of Romeo & Juliet, or a continuous track of Arden Forest bird-song during most of As You Like It, but we can be pretty sure that he was more concerned with the text than with the sound effects. When the famous actor-manager Sir Herbert Beerbohm-Tree produced a super-realistic production of As You Like It at the Haymarket Theatre in London, complete with real grass, foliage and rabbits, one critic complained that, ‘You couldn’t see Arden Forest for the Beerbohm Trees’.

I’m not advocating a purist approach to all classical drama, or that we return to the days of mechanical sound effects – apart from anything else, no theatre company would be able to afford the sheer manpower (eleven people for The Ghost Train) required to make those effects happen in the theatre – and of course, final consideration must always be given to the overall vision of the director, who may well feel that the use of sound and music will greatly enhance the written word. What I do suggest is that when you approach a period piece of work, you stop and consider why the effect is there, and how it might have been integrated into the production at the time it was written.

In Heartbreak House, for example, the final act includes references to an airship flying overhead and dropping a series of bombs that gradually get louder and louder. Shaw has the actors refer to the sound of the airship as being musical – like Beethoven, a great drumming in the sky. This almost certainly gives us a clue as to how the noise was produced; in all probability a bass drum and maybe a cello or a double bass live in the wings of the theatre produced a constant drone. The musicians could easily vary the level of the effect so as not to mask the dialogue, just as today’s sound engineer can reduce the level of the fader on the mixing desk. The more distant explosions would have been produced with drums, whilst the closer explosions would have involved a type of pyrotechnic known as a thunderflash, or theatrical maroon.

Taking this as a starting point, in the late John Dexter’s production of the play at the Haymarket Theatre, London, in 1983, I used a stock recording of an airship, but mixed it with a recording of a cellist bowing two strings simultaneously and varying the pitch of one slightly to produce randomly pulsating ‘beat frequencies’. I have used the resulting sound, with some modification, for two further major revivals of the show; without the musical element of the cello the effect would not be nearly so powerful.

Some of the mechanical devices used in the early part of the twentieth century are still in daily use in modern theatre: the ‘door-slam’ device, consisting of an open-backed box with a scaled-down door and various types of lock, chain, knocker and latch can be found in most theatres. Others, such as ‘wagon trolleys’, small trucks loaded with weights and with uneven wheels, meant to simulate the sound of horse-drawn carts and carriages, have long since disappeared, banished into the mists of time by high-quality portable loudspeakers and digitally recorded library effects. But banished along with them was the physical effect of mechanical vibration that they achieved. Sound designers who have attempted to recreate the train effect in The Ghost Train can testify to the difficulty experienced in attempting to reproduce the set-shaking effect of pulling a heavy garden roller over wooden slats nailed to the stage floor.

In the world of musical theatre, there is another lesson to be learned. Before the advent of amplification, composers, arrangers and directors had two major resources to call on: how the song was arranged, and which singer was going to deliver it. Singers were cast on their ability to project a song lyric to the rear of a large auditorium without the need for amplification, and musical scores were arranged so that the vocal line fitted into spaces left in the orchestration. Once again, I’m not simply being nostalgic; in a world where advanced sound and music technology is freely available to composers and sound engineers, the craft of the sound designer can all too often simply replace the skill of the artist. It can be argued that, for example, the use of wireless microphones allows more freedom in the choice of actor who can be cast in a musical, and that modern musical staging is far more exciting than it was fifty years ago, and I do not disagree with this. However, it also encourages performers to rely on technology to make up for weaknesses in basic performance techniques. There is no substitute for properly trained vocal projection skills, as many performers who have spent their lives in film and television discover when they make their first foray into live theatre.

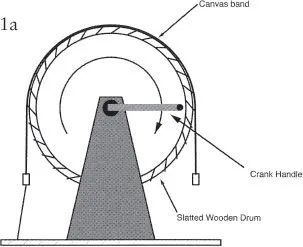

Figure 1a A Wind Machine: the handle turns a slatted drum against a strip of canvas.

Figure 1b A Rain Box: the box is rotated causing the dried peas to run from one end to the other. The pegs cause the peas to move around in a random fashion.

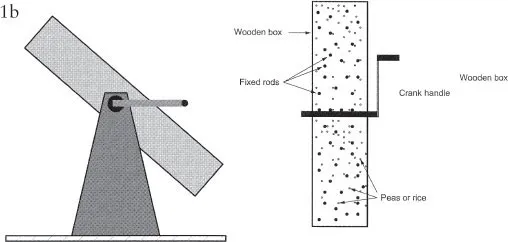

Figure 1c A Thunder Run: cannon balls are dropped into the trough and allowed to roll down to generate thunder sounds.

This can also apply to straight plays. I have seen a number of film and television stars come to grief when faced with a supporting cast of experienced, classically trained actors and a theatre that has no desire to employ a vocal reinforcement system. Inevitably, the untrained voice cannot compete with the trained voice and the result is almost always a barrage of complaints to the theatre about the inaudibility of the star of the show. It may come as a surprise to North American readers of this book, that very few theatres in the UK use vocal reinforcement systems in straight plays as the practice is widespread in the USA.

As far as music is concerned, the synthesiser, sampler and computer-based music sequencers are now so freely available and inexpensive that they are often used in place of live musicians, both for straight plays and for musicals, where an imagined need to save money leads to whole string or woodwind sections being replaced by a single keyboard player and a bank of sound modules. No amount of technology can make up for the instant reactions and subtlety of shading that a skilled pit or session musician can bring to a performance, and we are in danger of producing a generation of composers, directors, sound designers and audiences who have never heard a live performance by real musicians.

It is tempting to believe that because we are so advanced technically in present day theatre, we should ignore the past and how our predecessors managed things. After all, we have a bewildering range of play-back options, from recordable Compact Discs (CD-R) to Random Access Memory (RAM) based systems; we have computers, samplers, synthesisers, digital signal processing, assignable mixing desks, smart loudspeakers and high power, lightweight amplifiers; and in the field of reinforcement we have the smallest of microphones that can be hidden in an actor’s hair and powerful miniature radio transmitters that can be hidden on an actor’s body.

The creative technicians who came before us initially had no access to stored sound, and only much later to disc and tape replay. There were no hidden microphones, no miniature transmitters, no artificial echo and reverberation devices, no compressors, no limiters, no digital delay lines, and far more basic microphones, amplifiers and loudspeakers, so why should we consider how they achieved their results?

I think that we can draw a parallel with the music recording industry here: most recording studios today have equipment that would astound the average studio engineer of thirty or forty years ago. However, that same engineer may well draw a few unfavourable comparisons with the work that he or she was doing with far less complex equipment. Listen to the Beatles’ recordings of the mid-1960s and marvel at the immense detail achieved by using a four-track magnetic tape-based recording machine and the most basic effects devices.

Tempting as it is to fill our studios and theatres with all the latest kit, and our productions with continuous sound effects and music, very often less is more. To give a final example, in W. Somerset Maugham’s play, Our Betters, the stage directions call for the sound of a pianola (a mechanical piano using punched paper rolls and a vacuum system operated by the player pedalling a pair of bellows) to be heard off stage. A point is given for the music to begin, and another for the music to stop, however in a recent production, the director was concerned that the constant background music would distract from some fairly crucial plot development. The answer was extremely simple: during the scene, various characters enter and leave the room; when the room door was open, we heard the pianola, and when the door was closed, we did not. The problem was solved by reducing the amount of sound in the show rather than increasing it. Ultimately, it’s intelligent and imaginative choices in the use of sound and music that counts in theatre, rather than how much equipment you’ve got at your disposal to reproduce it.

Chapter 2

Theatre Types

Over the past fifty years, there has been a change in the fundamental concept of the design of theatre buildings. Prior to the Second World War, most London and provincial theatres followed the same pattern: a proscenium arch divided the stage from a horseshoe-shaped auditorium, which usually consisted of seating at various levels. The stalls were at stage level, with a dress circle above, and then a balcony, often referred to as ‘the Gods’, where the seats were the most uncomfortable and also cheapest. Many of these theatres were built in the early nineteenth century, whilst some, like the Bristol Old Vic, survive from the mid-eighteenth century; sadly, many were destroyed in the 1940s as a result of bombing raids. Many European theatres are built along similar lines, but usually with the addition of a series of boxes around the side and rear walls of the auditorium.

After the Second World War, most new theatres were built to a number of different patterns, but rarely to the size and scale of their Victorian counterparts. Two notable exceptions to this rule are the theatre complexes of the Royal National Theatre and the Barbican Centre, until recently the permanent London base of the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC). The Royal National Theatre has three auditoria: the Cottesloe, a small ‘black box’ studio theatre; the Lyttleton, a small proscenium arch theatre with a two-level rectangular auditorium; and The Olivier, with a multi-level fan-shaped auditorium.

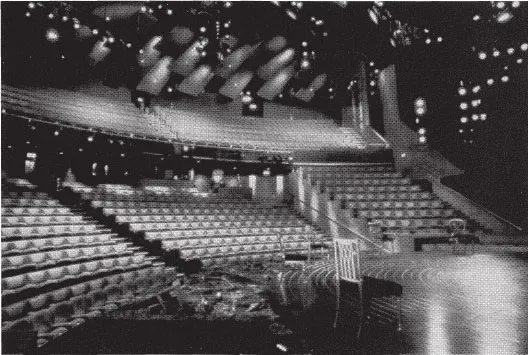

Figure 2 The Olivier Auditorium at the Royal National Theatre. Photograph by Mike Smallcombe.

The Barbican Centre has a large concert hall, as well as a 1,500-seat auditorium, and the Pit Theatre, a tiny studio theatre converted from a rehearsal room by the RSC’s in-house technical and design team responsible for shows at the RSC’s Stratford Studio Theatre, the Other Place (recently rebuilt).

The different styles of performing space break down into the following general categories: Proscenium Arch, Thrust Stage, Traverse, Theatre in the Round, Adaptable Spaces and Promenade Performances.

It’s worth taking a quick look at each type, and some of the problems that they throw up, before we move further into an examination of theatre sound systems.

Finally in this chapter, I will address the problem of control areas for sound in theatre.

Proscenium Arch

The auditorium of this type of theatre is separated from the (usually) raised stage by a large arch, and sometimes a pit in front of the stage which accommodates an orchestra. There is almost always space at the sides of the proscenium arch to allow loudspeakers to be mounted one above the other to cover the auditorium, but the rear of the auditorium is sometimes difficult to reach with a proscenium-mounted loudspeaker, so for amplified musicals it has become customary to mount delay loudspeakers under the circle and balcony overhangs, a technique discussed in Chapter 5.

On stage, the sound designer is normally restricted to placing loudspeakers at the sides and corners of the stage, to allow for the entrances and exits of actors and the movement of scenery on and off stage. Speakers can be hung from flying bars over the stage for thunder or bird-song effects, and the stage, particularly in older theatres, is often well supplied with small trapdoors called dip-traps that allow cables to run under the stage floor for safety and convenience.

The biggest problem with most proscenium arch theatres is their age. Built in an era before amplification was the norm, they provide little in the way of access and space for installing amplifiers, mixing desks and the o...