For decades, the Cross Creek School District has had the reputation of being one of the state’s worst school systems. So, after James Eagan became state superintendent, he decided to visit the district to see firsthand if that standing was warranted. Accompanied by the district superintendent, he walked through each of the district’s five school buildings, talked to the principals and several teachers at each site, and met with the school board president briefly after finishing the tour. When Dr. Eagan returned to the state capital, he told his deputy, “Without a doubt, this school system has the most deplorable facilities I have ever seen.” He then detailed conditions that contributed to his evaluation.

• None of the three elementary schools had either a media center (library) or a computer lab. In fact, most elementary school classrooms did not have a single computer.

• Though all three elementary schools had small kitchens, two of them did not have cafeterias—students ate their lunches in either classrooms or hallways.

• The middle school, originally constructed as a high school in 1925, had very small classrooms, some with wooden floors. There was one small computer lab located in what had been a storage room. The building was generally dirty and a musty odor was pervasive.

• The high school, the district’s newest facility, had been constructed 38 years ago. Since then, the building had not been renovated. Like the other schools, it provided little more than a basic shelter; most classrooms and the media center were small, the two science labs had outdated equipment, and access to computers was limited.

After sharing his perceptions, Dr. Eagan asked his deputy to conduct additional research on the district. Specifically, he wanted student data such as test scores, attendance figures, and graduation rates; he also requested fiscal data, such as tax rates, employee salaries, and per pupil expenditures. As expected, both sets of figures were low when compared with state averages. Approximately 40 percent of the students who enrolled at Cross Creek High School did not graduate; of those who did, only 13 percent continued their formal education and only 9 percent enrolled in 4-year colleges. The district ranked in the bottom 5 percent on the mandated state achievement tests. Fiscal data were equally depressing. Among 292 districts in the state, Cross Creek ranked last in the general fund tax rate (for operating expenses), 254th in the student transportation tax rate, last in the debt service tax rate (the district had no outstanding debt for school construction), 290th in average employee salaries, and 289th in per pupil expenditures.

Convinced that conditions in Cross Creek were inadequate, Dr. Eagan, with the unanimous support of the state board of education, wrote a letter to Cross Creek’s superintendent and board president. He warned that, unless the school board took action to improve the district’s facilities, he would recommend that the state board of education assume responsibility for operating the district—an option that rarely had been deployed in the state’s history.

After receiving the letter, the Cross Creek superintendent met with the school board and the district’s administrative staff. Though several principals urged the board members to reconsider their stance toward construction projects, their comments fell on deaf ears. Convinced that their political stance accurately reflected the will of most stakeholders, the board held a public meeting to discuss Dr. Eagan’s threat. Two days later, the following letter, co-signed by the school board president and superintendent, was sent to the state superintendent.

Mr. Eagan,

The school board held a public forum 3 days ago to discuss your letter. A large number of residents attended. With few exceptions, the residents of this school district said they do not believe they can afford to fund major school construction projects. All five school board members agree. Most residents in this district attended the local schools, and they believe a good education is not measured by walls and bricks. They disagree with your assessments of our buildings and challenge your authority to eliminate local control. Economically, this is a poor community. Most residents are barely able to pay their property taxes. If you and the state board of education believe new schools are a priority, then fund the projects entirely with state funds. We have no objection to this solution. Otherwise, we believe that while our schools are old, our staff and community spirit ensure that students are receiving an adequate education.

INTRODUCTION

In an information-based and reform-minded society, adjectives such as “adequate,” “efficient,” “effective,” and “good” (and their antonyms) have been used freely and carelessly to label schools. Because these adjectives have not been defined consistently, their connotations are imprecise. As demonstrated in the vignette about the Cross Creek school district, local stakeholders may see their schools as being adequate even though they are in a deplorable condition and lack basic features found in modern schools.

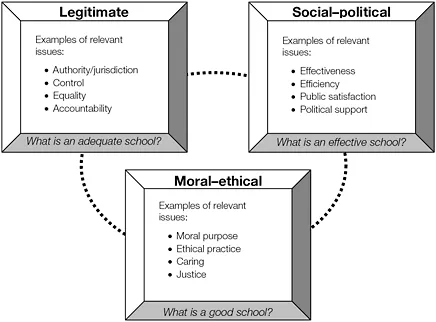

This initial chapter looks at schools from three critical perspectives (see Figure 1.1). The first, a legal point of view or legitimate frame, addresses both the issue of local control and the extent to which schools are adequate institutions providing students equal opportunities. The second, a social–political point of view, addresses the extent to which schools are viewed as efficient and effective institutions. And the third, a moral–ethical point of view, addresses the extent to which schools are viewed as good and caring institutions. Each frame, but particularly the legitimate one, is complicated by the increased involvement of federal and state authorities in elementary and secondary education.

In order to comprehend the challenges faced by contemporary principals, you need to understand the complexity of the institutions in which they practice. Thus, after reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

• Identify the federal, state, and local government responsibility for public education

• Explain the relationships among laws, district policies, and school rules

• Identify society’s interests in having efficient and effective schools

• Explain the importance of schools as moral institutions

• Express an understanding of the persistent tensions between societal and individual rights

• Differentiate the characteristics of adequate, efficient, effective, and good schools

SCHOOLS: THE LEGITIMATE FRAME

Legitimate refers to what is legal; legitimate authority, therefore, pertains to power granted through a legal system (e.g., constitutions, laws, legal precedents). In the case of public elementary and secondary education, legitimate authority is dispersed, with federal, state, and local agencies being involved, albeit to different degrees. Governmental control of public schools focuses most intently on three values: liberty, adequacy, and equality. Liberty relates to individual freedom; in the case of education, it refers to citizen authority over schools (King, Swanson, & Sweetland, 2003). Adequacy is a relative concept in that it is continuously being redefined in a dynamic society; as an example, adequacy was redefined substantially after America transitioned from a manufacturing society to an information-based society (Schlechty, 1990). Fundamentally, this value deals with minimum acceptable levels, such as a minimum number of attendance days, a minimum length for a school day, and a minimum number of credits for high school graduation (Kowalski, 2006). Equality is defined as reasonably equal educational opportunities (King et al., 2003); often defined in terms of just and equitable distribution of resources, equality in a given state is measured by variations in revenue and spending among local districts (Crampton & Whitney, 1996). A school failing to provide reasonably equal opportunities for students (compared with those offered by other schools in the same state or district) may also be inadequate.

The concurrent pursuit of liberty, adequacy, and equality spawns legal conflict as demonstrated by lawsuits challenging state funding laws for public schools. For example, when local districts have had total or substantial leeway to raise revenues from the local property tax (i.e., considerable liberty), wealthy school systems have typically had much higher per-pupil expenditures than have poor school districts.1 From a legal perspective, this condition can be problematic because opportunities afforded to students in wealthy districts are likely to exceed those afforded to students in poor districts. Moreover, the extent to which all districts in a state provide adequate educational opportunities is likely to vary. When a state’s system of public elementary and secondary education is deemed by the courts to be inadequate or unequal, judges have commonly mandated state legislatures to fix the problem. At the same time, however, the courts have commonly found that some degree of inequity is acceptable in order to preserve liberty (King et al., 2003). Consequently, the legitimate frame of schools is basically characterized by two difficult assignments: balancing liberty, adequacy, and equality within a state and balancing federal, state, and local authority.

Federal Authority

The U.S. Constitution does not mention education; thus, under provisions of the Tenth Amendment (powers not delegated to the federal government by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states or to the people) education is deemed a state’s right. Though public education remains a state responsibility, the federal government’s role in this service has expanded, especially during the last half of the twentieth century. Justification for increased involvement has been based on the legal interpretation that the federal government may intervene if issues being addressed in or by schools are germane to the U.S. Constitution (including amendments) and federal laws.

Incrementally, the federal role in public elementary and secondary schools has become broader and more overt (Robelen, 2005). Support and opposition for federal interventions, however, have been inconstant, with political positions usually determined by the specific issue being addressed. Generally, dispositions toward federal involvement reflect the overall philosophical division in society (Radin & Hawley, 1988). Today, all three branches of the federal government intervene in public schools.

Legislative Branch

The federal government can influence education by passing legislation deemed to serve a national interest by virtue of improving the effectiveness of public schools (LaMorte, 1996). Historically, Congressional involvement has produced four overriding themes: (a) constitutional rights of citizens, (b) national security, (c) domestic problems, and (d) concerns for a healthy economy (Kowalski, 2003). Since 1957, for example, the U.S. Congress has enacted several major laws that profoundly influenced curriculum, instruction, and governance. Four examples are identified in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Examples of the Federal Government Exerting Legitimate Authority through Legislation

Judicial Branch

Federal courts may become involved in public education when pertinent federal law displaces inconsistent state law (Valente, 1987). Most notably, interventions have been based on applying the strict scrutiny standard to interpret the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution—an amendment intended to protect citizens and their individual rights from “various forms of arbitrary or capricious state action” (LaMorte, 1996, p. 5). In addition to establishing jurisdiction by litigation involving a federal constitutional question or federal statute, federal courts also may do so when litigants reside in more than one state (Reutter, 1985). Issues such as parental rights, student rights, the rights and authority of school officials...