eBook - ePub

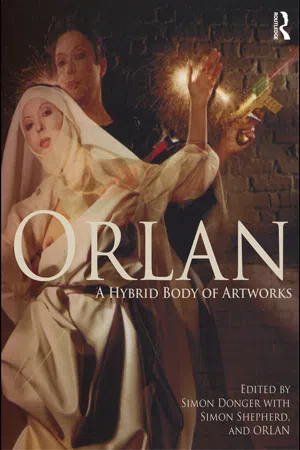

ORLAN

A Hybrid Body of Artworks

Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd, Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd

This is a test

- 216 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

ORLAN

A Hybrid Body of Artworks

Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd, Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

ORLAN: A Hybrid Body of Artworks is an in-depth academic account of ORLAN's pioneering art in its entirety. The book covers her career in performance and a range of other art forms. This single accessible overview of ORLAN's practices describes and analyses her various innovative uses of the body as artistic material.

Edited by Simon Donger with Simon Shepherd and ORLAN herself, the collection highlights her artistic impact from the perspectives of both performance and visual cultures.

The book features:

-

- vintage texts by ORLAN and on ORLAN's work, including manifestos, key writings and critical studies

-

- ten new contributions, responses and interviews by leading international specialists on performance and visual arts

-

- over fifty images demonstrating ORLAN's art, with thirty full colour pictures

-

- a new essay by ORLAN, written specially for this volume

-

- a new bibliography of writing on ORLAN

-

- an indexed listing of ORLAN's artworks and key themes.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es ORLAN un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a ORLAN de Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd, Simon Donger, Simon Shepherd en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Art y Artist Monographs. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

PREFACE 1

Restless corporealities

SIMON DONGER

In the early 1960s, as the inventors of ‘living-paintbrushes’ (the pinceaux vivants of Yves Klein) and of ‘living sculptures’ (the sculture viventi of Piero Manzoni) were prematurely departing the world, the live body as art made its emphatic arrival as both produced and producer.

1964:

• Action Or-Lent, ORLAN walks in slow motion on the streets of her hometown, Saint-Etienne, France;

• In New York, Carolee Schneeman performs Olympia’s stillness for Robert Morris’s Site;

• In Kyoto, Cut Piece has Yoko Ono sitting still, while her outfit is cut from her skin;

• In Vienna, Ana sees Günter Brus slowly painting himself white.

A few years later, Gilbert and George would become living and singing sculptures, Chris Burden would lie in bed for twenty-two days for his Bed Piece, and Marina Abramovic would stand up frozen, naked, under the assault of her viewers incising her skin in Rhythm 0.

The traces of performance are nothing less than a classical painting: both are the bits and pieces left after a moment of energy that a body has given, both could be said to be a still-life with fossilised elements of that body.

(ORLAN in Donger 2009)

Archives of the works mentioned above rarely present them from beginning to end but almost always depict the work at a point during its development. How the performance starts and ends is left to one side, in order to focus on a body-in-progress. Seriality and the repetition of movements and structures constitute additional strategies to prevent the body from becoming stabilized within the aesthetic frame. Those apparently peaceful bodies encompass restless corporealities.

The new art body had a different relationship with words and concepts. The debates provoked by the work of art no longer issued from a body through its discourse and its objects, but in reverse order, where the discourse of the concept became embedded in the body, corporeal. The body is then the unfixed canvas where issues are rehearsed, sometimes even cutting deep into the skin.

The slow-motion, if not static, body of art that emerged in the 1960s established a sensual connection to the fixity of painting and sculpture, usually resulting in the medium of photography. In this development, action is always twofold: real and remediated. ORLAN’s practice gives equal emphasis to both, constantly moving between the living flesh and the static object. But, although echoing various art movements, ORLAN’s practice defines its own idiosyncratic project under the name of Carnal Art.

From her earliest work onwards, ORLAN’s Carnal Art was deployed in the studio as well as outside; in the streets of her home town, markets and gardens in Portugal, religious sites in Italy, museums in France, Germany, the United States, and, later, having her body opened live in clinics in New York and Australia. Collaborating with surgeons, architects, photographers, designers, geneticists, directors, theorists…while crossing media and geographic borders, ORLAN has negotiated her own path through a variety of visual forms such as sculpture, graphic and product designs, video, cinema and digital media, architecture, fashion and bio-art.

Her work has been shown and known around the world as much as in her own country. She has participated in major group exhibitions and seen retrospectives of her work many times. She has talked and taught internationally. There are four decades not simply of artworks but of series which, like tentacular rhizomes, mirror and cross-fertilize one another. Yet, although large and lush monographic publications have appeared, no in-depth academic account of ORLAN’s work has been presented until today.

Previous publications have often emphasized conceptual frameworks such as feminism and psychoanalysis, since these are explicit in ORLAN’s discourse about her own work. Here we have chosen instead to organize a balance between her discourse and artworks on the one hand, and, on the other, a series of voices offering a variety of approaches to the work. To this end, we have juxtaposed in each section ORLAN’s voice with parallel discourses which enter into more or less obvious dialogues with the artist. The range of new essays printed here represents a transgenerational, transcultural and transdisciplinary collection of voices: curators, philosophers, historians, anthropologists, theorists and creators. They produce a multifaceted account which is structured around archives that run from ORLAN’s first works in the 1960s to her most recent pieces.

Aimed at dispelling some of the myths about ORLAN’s work and thus encouraging a wider engagement with her art, the present book covers and reflects on the restless hybridity in ORLAN’s body of artworks, framed within a loose chronological sequencing in line with the artist’s own mode of progression:

1 Seminal archives is a chronological set of past writings containing manifestos and key artworks by ORLAN, accompanied by cultural commentaries contemporaneous with the works: the series of site-specific performances called MesuRages, and the character of Saint ORLAN in its three phases—the interactive performance The Kiss of the Artist (1977), the multimedia series of Drapery—The Baroque (1979–86) and the surgery-performances of The Reincarnation of Saint ORLAN (1990–93) initiated by the Carnal Art Manifesto.

2 Open bodies is introduced by a conference paper that ORLAN has developed and updated over numerous years: This Is My Body… This Is My Software is a reflection In the present of 2008, on the thread of religion in her art, and thus focuses specifically on the works on Saint ORLAN. Her text is followed by four essays that describe and analyse key themes such as drapery, the Carnivalesque, the Baroque, surgery and pain.

3 Hybrid bodies opens with a new text by ORLAN specifically written for this volume. It uses the theme of suture to link, chronologically, her first performances to her most recent series of collaborations. Four essays then consider and respond to important aspects of ORLAN’s art since the surgery-performances, highlighting in particular hybridity in various different contexts such as the biogenetic, media, history and social anthropology.

4 Current dialogues allows the book to end with ORLAN’s contemporary voice in discussion with three major experts: curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, philosopher Paul Virilio, and cultural theorist Sander L.Gilman. The interviews cover, in retrospect, ORLAN’s entire career up to her current and emergent research, practice and interests.

Although comprehensive in intention, the book does not seek to reproduce all of ORLAN’s artworks. There is a great number of these: indeed, even on the verge of going to print, images of works which were thought to have lost all documentation are being rediscovered, dug out of ORLAN’s archives. The spectacular complexity and richness of her career to date make it literally impossible to compile every artwork, and thus every part of every series, into one publication. Indeed it is a tribute to her work that anyone wanting to explore it will find at first some key and straightforward pieces, but these are like the tips of various icebergs, like various Klein bottles, assembled one in another. The serial nature of her artworks makes the exploration into an adventure in a labyrinth, so that, on returning to the iceberg tips—The Kiss of the Artist, or the surgery-performances—a new descent begins, into other artworks, other series. It is this oscillating process of exploration that we have tried to replicate in the structure of the book. It is our hope that this both fairly reflects the artist’s own approach to making art and facilitates the journey through the works, provoking in the reader a desire for a yet deeper engagement with ORLAN’s creations.

PREFACE 2

The matter of ORLAN

SIMON SHEPHERD

It begins in the 1960s. Often seen as the point of ‘crisis of modernity’ and the turn towards postmodernism, these years produced the political and ideological conflicts that erupted into the famous events of 1968. Among their legacies thereafter was a refashioning of the relationship between culture and life. That refashioning is described thus by Fredric Jameson in his account of the period:

with the eclipse of culture as an autonomous space or sphere, culture itself falls into the world, and the result is not its disappearance but its prodigious expansion, to the point where culture becomes coterminous with social life in general; now all the levels become ‘acculturated’, and in the society of the spectacle, the image, or the simulacrum, everything has at length become cultural.

(Jameson 1988:201)

This merging of culture and life was no accident. It was in fact politically motivated. Writing in 1961, Henri Lefebvre describes the reaction against a high art which repeated traditional classicism, was abstracted, and had become separated from life. This was an art very different from the art of modernism, which aimed to engage with and yet critique social life. Against the newly abstracted high art a new avant-garde youth culture was working to subsume art into life: ‘they are continuing what they perceive as the revolutionary aspects of Surrealism, while rejecting its aesthetic. Thus, in their judgement, art has had its day and is being subsumed in ways of living, of loving, of playing and of working’ (Lefebvre 1995:345). Lefebvre’s account here is influenced by the political grouping to which he was close, the Situationists. For the leading philosopher of Situationism, Debord, what was wrong with capitalist society was symptomized by the spread of advertising. This drenching of social life with commercially organized images led to an experience, indeed a way of living, that was non-participatory, with society simply there to be watched as spectacle. ‘It is not just that the relationship to commodities is now plain to see—commodities are now all there is to see; the world we see is the world of the commodity’ (Debord in Plant 1992:12). As Lefebvre put it, while the influence of mass media may have improved the general level of culture, it had done so at a cost of undermining ‘the unity of culture and nature’ (Lefebvre 1995:336). A Situation, on the other hand, is something made to be lived by those who construct it.

Now in the concept of that opposition between an autonomous, abstracted high art and an art blended with life, there’s a problem. As we have seen, any form of abstracted art ceases to be able to have a critical function in relation to social life and the more withdrawn it becomes, the more it vanishes as a category of human production. But the real problem in this opposition has to do with the fact that life, in general, is dominated by the society of the spectacle. If high art is disengaged, the alternative to it sails dangerously close to full immersion in the very form of society which devalues participation and offers itself as spectacle. It thus became possible after a decade to view the effect of the 1960s as issuing in several different forms of conservatism. These are described in Jurgen Habermas’s three categories of artists who in different ways resisted modern art’s critical relationship with social life. First, the ‘young conservatives …claim as their own the revelations of a decentered subjectivity, emancipated from the imperatives of work and usefulness, and with this experience they step outside the modern world’ (He specified a line of thinkers from Bataille via Foucault to Derrida.) Next, the ‘old conservatives’ who ‘do not allow themselves to be contaminated by cultural modernism’ and ‘recommend a withdrawal to a position anterior to modernity’. Last, the ‘neoconservatives welcome the development of modern science, as long as this only goes beyond its sphere to carry forward technical progress, capitalist growth and rational administration’. All lead to ‘confinement of science, morality and art to autonomous spheres separated from the life-world and administered by experts’ (Habermas 1985:14). Habermas’s observations were made in 1980. By now ORLAN had been working for about fifteen years.

She had started in 1964, in the middle of that vexed period. As she herself later noted, when she began ‘art was engaged with the social, the political, the ideological’ (ORLAN 1998:317). Indeed for her as a woman the making of art was itself always going to be political. We can get a sense of this if we return to a chunk of Lefebvre’s account which I omitted before.

For him the activists of the avant-garde and youth culture were young men. Women did not play much of a part. Indeed their part was more evidently played on the other side, within the society of the spectacle itself where the dominance of mass media leads to ‘an abstract artificiality posing as naturalness, and a po-faced aestheticism masquerading as art and creativity’. This aestheticism cannot distinguish between the collection of art objects and ‘aesthetic activity’: ‘its main social support is women’ who ‘act as its agents’ (Lefebvre 1995: 336). For a young woman in a provincial town in the mid-1960s, a performance in a public space was somewhat at odds with the role of agent of aestheticism, yet not, by definition, the same thing as a male youth living the situation he had constructed.

This rather general sense of her origins—a time when art and politics were connected—is something which has not received much elaboration by those who comment on ORLAN’s work. Perfectly reasonably, commentators, who are often working within a biographical mode, pick up on references and suggestions made by the artist herself. In general the contexts offered for discussion of ORLAN’s work include feminism and feminist art, Lacanian psychoanalysis and cyborgism. Other contexts are extrapolated, albeit wrongly, from the work itself: surgery and body-opening. Kate Ince, for example, locates ORLAN in relation to French women’s writing since 1968 but notes the lack of influence of female visual artists in France (Ince 2000). O’Bryan (2005) links the work to feminist psychoanalysis and also writes about images of the opened body. A more precise contextualization is offered by genealogies of visual artists. Thus Augsburg (1998) says that Saint ORLAN evokes the spirit of Fluxus, while Kauffman (2005) reaches back earlier to make links beyond Fluxus into Viennese Actionism, Duchamp and Yves Klein. She gets closer to picking up on ORLAN’s own remark about her origins when she notes that ‘ORLAN’s early art suggests the kind of agitation synonymous with Debord and the Situationists’, adding that ‘In the wake of Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, ORLAN improvised a series of absurd feminist spectacles’, such as the MesuRages (2005:114). A seemingly more tangential, but perhaps more tantalizing, link back into that engagement between art and the political and ideological is contained by Augsburg’s suggestion of a similarity to the figure of Genet, via Sartre’s Saint Genet (1998:294). The link Augsburg finds is between artists who make out of the negativity directed at them an affirmation of identity. This, however, remains fairly typical of app...

Índice

Estilos de citas para ORLAN

APA 6 Citation

Donger, S., & Shepherd, S. (2010). ORLAN (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1610097/orlan-a-hybrid-body-of-artworks-pdf (Original work published 2010)

Chicago Citation

Donger, Simon, and Simon Shepherd. (2010) 2010. ORLAN. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1610097/orlan-a-hybrid-body-of-artworks-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Donger, S. and Shepherd, S. (2010) ORLAN. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1610097/orlan-a-hybrid-body-of-artworks-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Donger, Simon, and Simon Shepherd. ORLAN. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2010. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.