![]()

1

Self-Related Cognitions in Anxiety and Motivation: An Introduction

Ralf Schwarzer

Institut für Psychologie, Freie Universität Berlin

The cognitive approach has strongly influenced most areas of psychology and education. Attitudes, emotions, and actions are greatly affected by conscious or semi-conscious processes as found in perception, memory, thought, and language. The processing, storage, and retrieval of information are basic elements in the regulation of behavior and, thereby, are precursors of habit formation and personality development. Emotions are viewed as being dependent upon cognitions, or as being constituted by cognitions, feelings, and arousal in a complex manner. This will be discussed further within the context of anxiety. Self-focused attention can be a starting point for more elaborated cognitions about oneself, such as attributions, self-evaluations, and expectancies in stressful or demanding situations. Motivated actions are strongly determined by self-related cognitions. This introductory chapter discusses some recent advances in research on social and test anxiety, coping, self-evaluations, and motivation. The following chapters, written by well-known experts in these fields, will deal with these and related topics in detail.

SOCIAL ANXIETY

Social anxiety can be defined as consisting of (1) negative self-evaluations, (2) feelings of tension and discomfort, and (3) a tendency to withdraw in the presence of others. This is a pattern of cognitive, emotional, and instrumental variables which may occur simultaneously, but need not. Shyness, embarrassment, shame, and audience anxiety are different kinds of social anxiety. Shyness is a general social anxiety applicable to a variety of social situations. Embarrassment can be seen as an extreme state of shyness indicated by blushing. Shame occurs when one sees himself as being responsible for negative outcomes or for failing in public. Audience anxiety is characterized by a discomfort when performing in front of an audience (stage fright) which can lead to an inhibition of speech. This is closely related to test anxiety because the individual is afraid of being under the scrutiny of others. Both kinds of apprehension in face of tests and social interactions share this aspect of evaluation anxiety (Wine, 1980). Social anxiety is more general, whereas test anxiety can be conceived of as very specific with respect to written exams. In the case of oral exams and any other tests performed in public, test anxiety as well as social anxiety are adequate variables to be taken into account. Test anxiety researchers have usually neglected this social aspect or have defined test anxiety in a manner too broad to be of use.

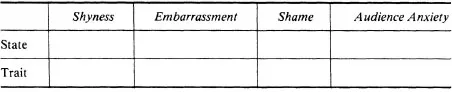

Whether social anxiety can be subdivided into these four emotions has not been finally agreed upon. There may be more or fewer facets. Buss (1980) has made this differentiation popular, but now undertakes a conceptual change by conceiving embarrassment as part of shyness (Buss, this volume). Some authors don’t make any distinction at all and prefer to accept social anxiety as one homogeneous phenomenon. In contrast, Schlenker and Leary (1982) conceive shyness and embarrassment as separate facets of social anxiety. This question requires further theoretical efforts. Table 1.1 shows a matrix of potential differentiations. It may be possible that some cells are empty, e.g., a trait of embarrassment may not exist.

Therefore, in the following discussion shyness as the most typical and well-understood social emotion is the focus of attention, representing social anxiety. It is useful to distinguish state shyness from trait shyness in accord with the widely accepted conceptualization of state and trait anxiety (Spielberger, 1966). The state of anxiety refers to the acute feeling in the process of emotional experiencing. The trait of anxiety refers to a proneness to respond with state anxiety in threatening situations. This proneness is acquired during the individual’s history of socialization. Shyness is characterized by: public self-awareness, the relative absence of an expected social behavior, discomfort in social situations, an inhibition of adequate interpersonal actions, and awkwardness in the presence of others. Buss (1980) claims that public self-awareness is a necessary condition of any kind of social anxiety. In this emotional state the person’s attention is directed to those aspects of the self which can be observed by others, like face, body, clothes, gestures, speech, or manners. At the trait level public self-consciousness is the respective variable. Persons high in public self-consciousness are prone to perceive themselves as social objects and tend to think and act in front of an imaginary audience. The direction of attention to the self can be understood as a mental withdrawal from the social situation at hand, leading to a decrement in social performance. Self-related cognitions are part of the complex emotional phenomenon of shyness or social anxiety in general (see Table 1.2).

TABLE 1.1

Potential Differentiation of Social Anxieties

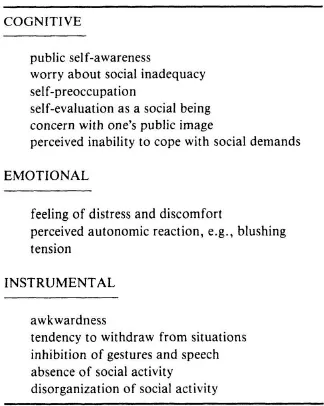

TABLE 1.2

Components of Social Anxieties

The anxious individual worries about his social performance, is concerned with his public image, perceives inability to cope with social demands, is apprehensive of behaving inadequately, permanently monitors and evaluates his actions, and is preoccupied with himself as a social being. The emotional component refers to the feelings of distress, discomfort, tension, and the perception of one’s autonomic reactions in the presence of others. For example, blushing when experiencing embarrassment, and being aware of it, can lead to a vicious cycle (Asendorpf, 1984). The “emotional component” can be seen as a “quasi-cognitive component” because it deals with information processing of feelings and arousal. Finally, the instrumental or action component refers to awkwardness, reticence, inhibition of gestures and speech, a tendency to withdraw from the situation, and the disorganization or absence of social behavior. Both shy and polite people can be very similar in behavior but differ in cognitions and feelings: non-shy, polite individuals are relaxed and calm, and direct their attention to the situation, whereas shy individuals do not. These three components have to be inserted in each cell of Table 1.1 and require a cell-specific theoretical elaboration.

Causes of shyness can be theorized in different ways. Schlenker and Leary (1982) propose a self-presentational view: Shyness occurs when someone desires to make a favorable impression on others but is doubtful of the desired effect. Embarrassment occurs when something happens which repudiates the intended impression management. There may be a discrepancy between one’s own standard of self-presentation and one’s actual self-presentation. When such a discrepancy is expected, shyness will result, and when it is actually perceived, embarrassment is experienced. This can be seen as a two-stage process at the state level of social anxiety. A person who expects to fall short in impressing others will be shy. If this anticipation becomes true, the person is embarrassed. Buss (this volume) mentions a number of other potential causes for shyness, such as feeling conspicuous, receiving too much or too little attention from others, being evaluated, fear of being rejected, a breach of privacy, intrusiveness, formality of social situations, social novelty, and so forth. With respect to common stress theories social anxiety depends on the appraisal of the social situation as being ego-threatening and the appraisal of one’s own inability to cope with it.

The development of shyness can be traced back to two sources (Buss, this volume). The “early developing shyness” appears in the first year of life and is better known as stranger anxiety or wariness. Novelty, intrusion, and fear of rejection are the immediate causes. Since there are no self-related cognitions at that time, this is a fearful shyness, whereas the “later developing shyness” can be regarded as a self-conscious shyness. It first appears in the fourth or fifth year of life and is associated with acute self-awareness and embarrassment. Both kinds of shyness contribute to the complex phenomenon of shyness during the individual socialization process. Fearfulness as an inherited trait and public self-consciousness as an environmental trait may be two sources of trait shyness, which attains its peak degree during adolescence (Buss, this volume). Low self-esteem and low sociability may be two additional causes. In a field study with 94 college students, we obtained satisfactory correlations between shyness on the one hand and, on the other self-consciousness (.39), audience anxiety (.39), general anxiety (.36), other-directedness (.36), and self-esteem (–.62) (Schwarzer, 1981). These may be rough indicators of trait associations.

There are few measures designed to assess trait social anxiety. As in test anxiety research, separate worry and emotionality scales have been constructed (Morris, Harris, & Rovins, 1981). However, these scales do not distinguish shyness from embarrassment, shame, and audience anxiety. Additionally, the specific shyness scale of Cheek and Buss (1981) does not provide a separation of cognitive and emotional components. Evidently there has been a lack of operationalization compared to the obvious increment in theoretical efforts during the past few years. A complex measure of social anxiety which satisfies the needs of the present approach should consider the four kinds of social anxiety and the state-trait distinction (Table 1.1) as well as the three components (Table 1.2), and also provide as many subscales. The distinction between a cognitive and an emotional component bears treatment implications: Self-related cognitions could be modified by a restructuring and attention training, whereas tension and nervous feelings could be treated by systematic desensitization.

TEST ANXIETY

Anxiety can be defined as “an unpleasant emotional state or condition which is characterized by subjective feelings of tension, apprehension, and worry, and by activation or arousal of the autonomic nervous system” (Spielberger, 1972, p. 482). Test anxiety is a situation-specific state or trait which refers to examinations. As mentioned above, this may be confounded with social anxiety when the test is taken in public or when social interactions are part of the performance to be evaluated. Test anxiety theory has a long tradition which makes it one of the most studied phenomena in psychology (Morris & Ponath, this volume; Tobias, this volume). However, as paradigms shift in our general psychological thinking, this has a strong impact on the investigation of specific phenomena, too. The cognitive approach to emotions and actions has given rise to new concepts which are fruitful in understanding and explaining the subjective experience of anxiety in specific situations. The first four volumes of the new series Advances in Test Anxiety Research demonstrates the far-reaching consequences of cognitions of the worry type for our scientific knowledge (Schwarzer, Van der Ploeg, & Spielberger, 1982, Van der Ploeg, Schwarzer, & Spielberger, 1983, 1985).

Tests are mostly regarded as general academic demands in schools or in higher education, but also can be conceived of as highly specific demands, as discussed in mathematics anxiety (Richardson & Woolfolk, 1980) or sports anxiety (Hackfort, 1983). Such demands, if personally relevant for the individual, can be appraised as being challenging, ego-threatening or, harmful (Lazarus & Launier, 1978). The appraisal of the task as ego-threatening gives rise to test anxiety if the person perceives a lack of coping ability. This second kind of appraisal is most interesting for the study of self-related cognitions. The individual searches for information about his specific competence to handle the situation. The coping resources looked for could be one’s ability to solve the kind of problem at hand or the time available and the existence of a supportive social network (see B. Sarason, this volume). Perceiving a contingency between the potential action and the potential outcome and attributing this contingency to internal factors is most helpful in developing an adaptive coping strategy. This confidence in one’s ability to act successfully can be called self-efficacy (Bandura 1977). A lack of perceived self-efficacy leads to an imbalance between the appraised task demands and the appraised subjective coping resources, resulting in test anxiety, which inhibits the ongoing person-environment transaction and decreases performance. This is a case of cognitive interference (I. Sarason, this volume). The individual’s attention is divided into task-relevant and task-irrelevant aspects. The presence of task-irrelevant cognitions can be regarded as a mental withdrawal (Carver & Scheier, this volume). People who cannot escape from an aversive situation physically because of social constraints or lack of freedom to leave, do so by directing their thoughts away from the problem at hand. Task-irrelevant thoughts can be divided into self-related cognitions (like worry about one’s inability or failure) on the one hand and those which are totally unrelated to the task (like daydreams) on the other. This mental withdrawal from the threatening demands equals the test anxiety component which debilitates academic performance. The perception of discomfort and tension is the other component. Autonomic arousal may accompany this state or trait but need not. Mental withdrawal is maladaptive in a specific situation because it contradicts any kind of problem-centered coping action. However, in the long run there may also be a certain adaptive value because the person may learn to distinguish such situations from those which are easily manageable and, therefore, avoids selecting inappropriate situations or too difficult tasks.

There are many causes which make a person test anxious. The individual’s history of success and failure combined with an unfavorable attributional style (Wine, 1980) and no supportive feedback from parents, teachers, and peers may lead to a vicious cycle which develops a proneness to scan the environment for potential dangers (“sens...