![]()

Section Two

GEOMETRY

Section Two

GEOMETRY

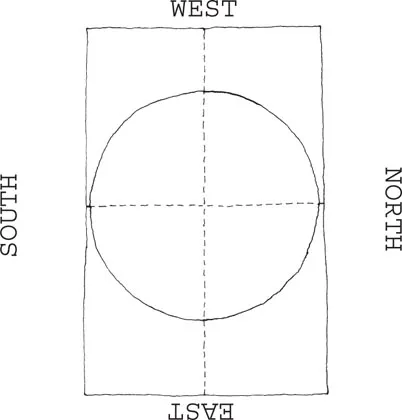

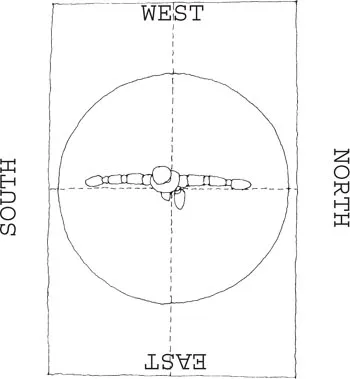

This second set of exercises focuses on the different geometries affecting architecture. Each of the ingredients of architecture has its own geometry. The world in which the products of architecture are built has, in its usual interpretation, a geometry of six directions. These are: east (where the sun rises); south (where the sun, at noon, is at its highest); west (where the sun sets); and north (where the sun never goes). (For the southern hemisphere, reverse the descriptions of north and south.) In addition, there are the vertical directions of down (the direction in which gravity exerts its force) and up (the direction of the sky above).

The person living on the surface of the earth can also be interpreted as having six directions: front (or forward); back (or backward); left (sideways); right (sideways); down; and up. The person projects the axis – from its eyes – of the line of sight; and, being able to move, the line of passage. Though people come in different shapes and sizes, the majority fit into a fairly limited range. The extent of a person's movement – pace, step up or down, reach, span (of arms or hand)... – also falls into a fairly narrow range. All these constitute the geometry of the person.

When people come together as groups they form patterns. This is social geometry. In that architecture sets the frames for what we do, it may respond to or set such social geometry in physical and spatial form.

The built form by which architecture is realised, and which (usually) mediates between the person and world, also has its geometries. These will be explored in the following exercises but they include, especially, the geometry of making (the ways in which the forms, properties and characteristics of building materials can influence the forms built from them) and the related geometry of planning.

The aspiration to ideal geometry – the imposition of perfect geometric figures – square, circle... cube, sphere... – onto architectural form – will be the subject of later exercises in this section.

Some of the geometries of being have been touched upon already in these exercises: the circle with its centre; the four horizontal directions associated with the axis (line of sight); the geometry of the person. Further discussion of the various geometries affecting architecture can be found in Analysing Architecture, ‘Geometries of Being’.

Sometimes these architectural geometries are in harmony, sometimes they are in conflict. In a work of architecture it is rare to be able to achieve a harmony between all the different kinds of geometry. In due course we shall look at some instances where this does happen.

![]()

EXERCISE 4: alignment

In this exercise, using your board, blocks and person(s), you will model the geometries of the world and of the person. You will also experience some of the restrictions/conditions that the geometry of making imposes on building (i.e. realising works of architecture in physical – material and spatial – form). Your simple wooden blocks are not real building materials but they do share some characteristics with proprietary materials available for constructing real buildings that must stand on the ground under the force of gravity. The chief of these characteristics relate to the blocks’ geometry: their (precise) rectangular form; their standardised dimensions; and their simple proportions of 1:1, 1:2, 1:3...

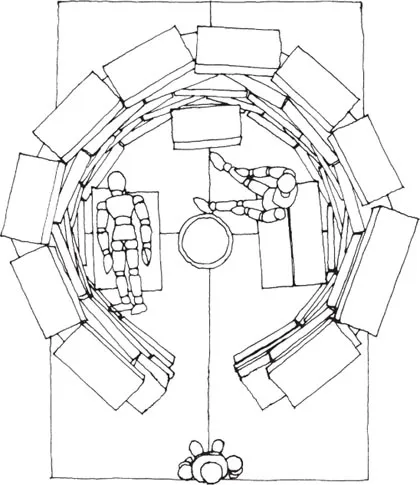

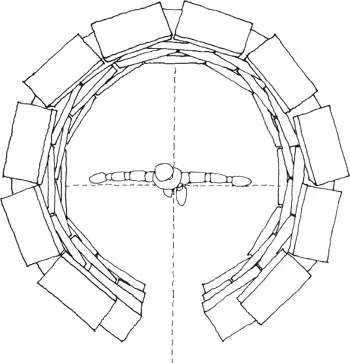

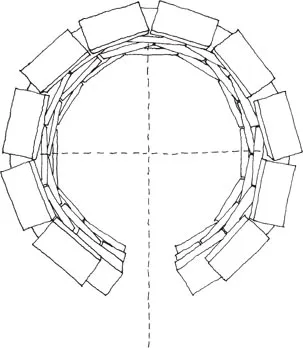

We can use the circular house built in Exercise 2 to explore the different sorts of geometry that compete for attention and dominance in architecture.

EXERCISE 4a. Geometries of the world and person.

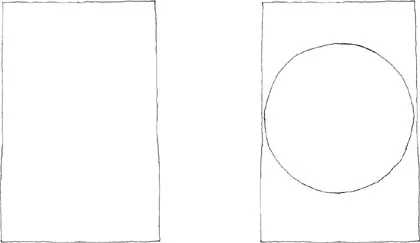

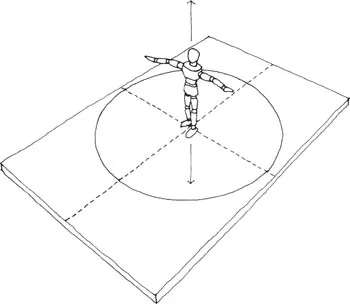

Without the house your board has its own geometry. It has four sides; it is rectangular; its opposite sides are parallel; its corners are right angles; it is flat and horizontal.

Your board also has a centre around which a circle of place might be drawn.

With the two axes indicating the four cardinal directions your board can be seen as a simple diagram of the world.

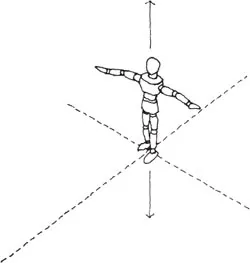

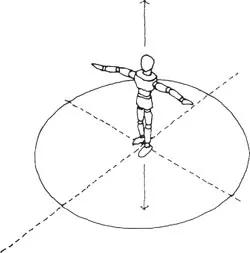

Your person has its geometry too.

The person has four aspects: front; back; left; and right, which project axes in each of the four directions. It also has an ‘up’ direction, stretching into the sky; and a ‘down’ pressing into the ground, the direction of the pull of gravity.

The person is its own, mobile, centre, around which the person's own circle of place may be drawn.

EXERCISE 4b. Geometries aligned.

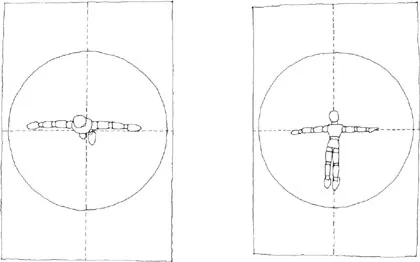

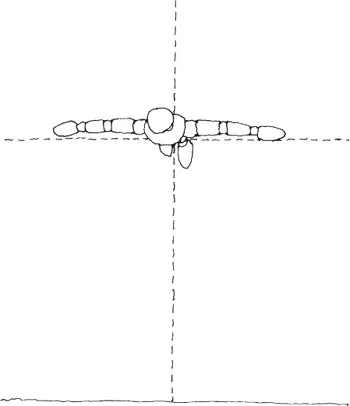

Position your person on the board, at its centre, so that its geometry is aligned with that of the board.

This alignment, between the geometry of the person and that of the board, may be achieved whether the person is standing or lying down.

The centres, axes and circles of place of the person and of the board coincide.

And, since the board is a simple model of the world, we can see that there are situations where the geometry of the person can be aligned with that of the world. (It might be argued that we interpret the world around us in terms of our own geometry.)

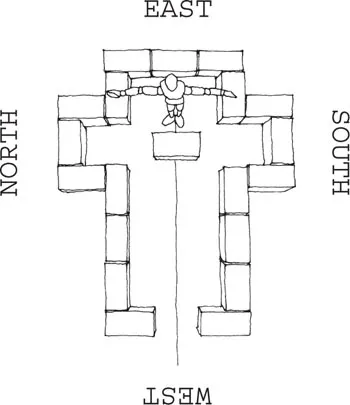

A Christian church is an alignment of the geometry of the crucifix – which represents the geometry of a person – the geometry of the altar, the geometry of the building and, since the building is oriented east-west, the geometry of the world.

That alignment of geometries might be between the person and the cardinal directions – north, south, east, west – but it may also be achieved in relation to some other datum: the sea with its distant horizon; a wall (the Western Wall in Jerusalem, for example); a remote focus (the Ka'ba in Mecca, for example); or just the street outside your house.

EXERCISE 4c. Architecture as an instrument of alignment.

You can see then that when you rebuild your wall around the circle of place, leaving a doorway for access, you are creating an instrument that physically records and reinforces the alignment between the four-directional horizontal geometry of the person and the four-directional horizontal geometry we ascribe to the world.

But whereas the person will move around and away, the geometry manifest in the building persists as a record and reminder of that alignment.

IN YOUR NOTEBOOK...

In your notebook... collect examples where architecture acts as an instrument of alignment. You should draw your examples as plans, simplified if you wish. Your examples should include those in which architecture aligns the person with the world and others where the architecture aligns the person with something else. You can find some examples in books on architectural history but you should also find some more recent examples, maybe in current architectural magazines, and examples from your own everyday life.

You have probably experienced the aligning power of architecture in your everyday life more often than you consciously acknowledge. For example, your own house might be aligned, through the orientation of its main doorway and windows, to: the sun in the south (north, in the southern hemisphere); a view of the sea and its distant horizon; the public road outside... You have also experienc...