![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction: the Reinvention

of the ‘New’ Berlin Post-1989

Of most cities people have a sort of image in their head; an image of what the city looks like through a collection of icons. Berlin does not have such an image. One cannot go to the central market place, or the grand palace, to look for its identity. The city is not beautiful, but presents itself more as a challenge. It pushes its visitors to explore it and ever again it confronts them with new and different perspectives, always postponing the moment where one gets a grip of it. Berlin is clumsily unfinished. Its appearances do not reveal its different meanings. (Cupers and Miessen, 2002, p. 58)

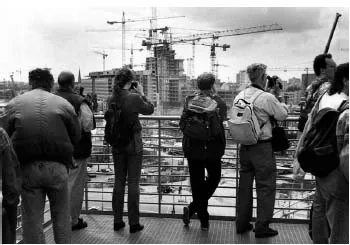

After the Fall of the Wall and the reunification of the city in 1989, a decade of intense and rapid urban development began in Berlin. In the mid-1990s visitors to the city's central areas were welcomed by an endless landscape of cranes and construction sites: around Potsdamer Platz, alongside the river Spree where the new seat of the German government was being built, around the old historical core of the Friedrichstadt. The scale and amount of redevelopment was, by European standards, striking. Omnipresent were the noise, the dust, the bustle and rustle of construction activity, the intriguing presence of large water pipes running up and down streets to drain the water away from the construction sites of a city built on sand and swamps. Equally striking was the highly visible presence of images and texts surrounding the construction sites: billboards featuring pictures of the architecture of the new developments under construction, a red information centre built on stilts displaying three-dimensional visualizations of the future Potsdamer Platz, exhibitions with large-scale models of the city, posters advertising guided tours of the construction sites, or observation platforms inviting the passer-by to peer into the construction process (figure 1.1).

The emerging landscape of the new Berlin under construction was not only being physically built, it was also staged for visitors and Berliners and marketed to the world through city marketing events and campaigns which featured the iconic architecture of large-scale urban redevelopment sites. Public-private partnerships were set up specifically to market the new Berlin to different target groups – potential investors, tourists and the Berliners themselves. Throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, a complex network of public and private actors were involved in practices of place marketing for Berlin, producing images of, and a discourse on, the city, urban change and place identity. The production of a new material built environment in reunified Berlin was accompanied by the ‘social construction of a particular image and meaning’ (Lehrer, 2002, p. 61). This formed part of the political responses to the enormous challenges unleashed by the Fall of the Wall and subsequent reunification of the city: the loss of the political ‘status of exception’, the retrieved status as capital city, intense economic restructuring, deep social and demographic transformation.

Figure 1.1.Watching the construction process at Potsdamer Platz from the viewing platform of the INFOBOX, Leipziger Platz (5 July 1996). (Source: Landesarchiv Berlin/Edmund Kasperski)

More than a decade later, in the spring of 2007, a headline displayed on the promotional TV screen of a Berlin underground carriage captured my attention: ‘Berlin turned into a brand. Wanted: a new slogan for the city’. This headline was intriguing. It seemed to ignore the fact that during the previous fifteen years, a plethora of activities of place marketing, slogan making, image production and architectural staging of all kinds had taken place in Berlin. Did that mean that those activities were deemed to have failed? That they had become irrelevant? Or that they needed a new, fresh orientation? Why did it still matter for Berlin's political leaders to search for a new image, a new slogan, a new ‘brand’ nearly twenty years after the Fall of the Wall and the reunification of the city? A glimpse at the local newspapers on the following day revealed that the then Mayor of Berlin had decided to launch a call for ideas for a new city marketing campaign.

Why has so much organized effort been put into the representation, visualization, communication, staging and marketing of urban change in post-Wall Berlin? By whom, for what audiences, and with what types of messages? Why do specific urban actors have ‘a collective interest in constructing meaning’ for particular localities (Le Galès, 1998, p. 502)? These initial questions formed the starting point of a decade of investigation into the urban transformation of Berlin after the Fall of the Wall, analyzed through the prism of place marketing practices and what I refer to as the politics of ‘reimaging’ the city. Place marketing refers to

the various ways in which public and private agencies – local authorities and local entrepreneurs, often working collaboratively – strive to ‘sell’ the image of a particular geographically-defined place, usually a town or city, so as to make it attractive to economic enterprises, to tourists and even to inhabitants of that place. (Philo and Kearns, 1993, p. 3)

Over the past thirty years urban governments around the world have increasingly invested in place marketing strategies as a response to the perceived heightened inter-city competition in a globalized economy, as discussed in Chapter 2. Practices of ‘imaging’ form a central component of such strategies. Urban policy-makers, in cooperation with other actors, have produced an increasing amount of public discourse about their city, largely based on urban images and representations of urban development conveyed through various media. This is influenced in part by the spread of new information and communication technologies and by the increasing importance of visual representation strategies in our image-saturated societies.

While cities as ‘collective actors’ have been producing more public discourse and imagery about themselves, urban researchers (e.g. human geographers, architectural and cultural theorists, urban sociologists and planning scholars) have increasingly focused their attention on ‘discourses’ and ‘representations’ as part of a discursive and visual turn in urban studies. These two related shifts – in practice and research – form the contextual background of this book. The book aims to contribute to a central issue in urban studies which is discussed in depth in Chapter 2: the relationship between ‘symbolic’ and ‘material’ politics in contemporary urban governance and urban planning.

In Berlin, the place marketing practices analyzed in this book are uneasily categorized, oscillating between traditional economic promotion, public relations and political communication. These activities should be read within the wider debates, which took place over more than a decade, on what the urbanism of the new Berlin should be about and what it should look like. Such debates were omnipresent in the city's physical and virtual public sphere: in the numerous planning and architectural exhibitions displayed in public buildings or private art galleries, in the public debates between built environment experts and politicians, in the daily articles of the press reporting planning and architectural controversies… The planning and physical production of a new built environment was shaped and accompanied by an incredible variety of discourses on the city and spatial images of the city, produced by politicians, planners, architects, the media, citizens’ groups, academics, city marketers… Alternative visions of the future of Berlin were debated, and communicated, through words, ‘maps, models of the city, virtual-reality simulations, newspaper articles, planning codes, architectural sketches, and even tourism practices’ (Till, 2003, p. 51) (figure 1.2).

Place marketing activities have thus formed part and parcel of the politics of urban development, i.e. the public debates, controversies, power struggles and political decisions made with regard to what gets built, where, by whom and for which uses and users (Strom, 2001). This politics of urban development has taken place in the context of dramatic changes in the political, economic and social structures of the city post-1989. But in a country undergoing a process of transition between two political regimes, in a city haunted by ghosts and remnants of its troubled past, the politics of urban development is also closely related to the politics of collective identity (re)construction: ‘alongside the new, gleaming corporate headquarters and government centers, Europe's largest building site [was] also the scene of the post-unification construction of German history and identity – ethically, politically, and … rhetorically’ (Jarosinski, 2002, p. 62). Within this process of identity construction, the spatial expression of conflicting and contested narratives has been highly visible (Neill, 2004, p. 10). Since 1989, intense debates and struggles as to which memories and symbols are to be preserved or destroyed in the urban landscape of the city have been taking place in Berlin (Ladd, 1997; Delanty and Jones, 2002; Till, 2005). Such struggles are not new: in Berlin the desired representations of the German nation have ‘continuously been materialized in space through planning and architecture, staged and performed, and re-shaped as a new political regime would emerge’ (Till, 2005, p. 39). Berlin's landscape is, in that sense, uniquely politicized:

Figure 1.2. Helmut Jahn (architect) and Volker Hassemer (director of the city marketing organization Partner für Berlin) explain the architecture, planning and construction of the new Potsdamer Platz at a press conference in the Sony Centre (15 July 1998). (Source: Landesarchiv Berlin/Barbara Esch-Marowski)

Each proposal for construction, demolition, preservation or renovation ignites a battle over symbols of Berlin and of Germany. None of the pieces of the new Berlin will present an unambiguous statement about Berlin's tradition or meaning, but most will nevertheless be attacked for doing so. Berlin faces the impossible task of reconciling the parochial and the cosmopolitan, expressions of pride and humility, the demand to look forward and the appeal never to forget. (Ladd, 1997, p. 235)

Scholars from various disciplines have explored, on the one hand, the use of the built environment in the political agendas of successive German regimes in a historical perspective, and on the other, the links between urban form, collective memory and national identity construction in the context of contemporary Berlin. The city ‘has become something like a prism through which we can focus issues of contemporary urbanism and architecture, national identity and statehood, historical memory and forgetting’ (Huyssen, 2003, p. 49). Place marketing practices, through their framing of the city's past, their staging of the present and their projected visualizations of particular urban futures, play a role in the construction process of collective identity and memory. The politics of image production and place marketing is consequently a politics of identity (Broudehoux, 2004, p. 27), because of the specific use (and reconfiguration) of culture and history involved. There is an abundant literature on the urban transformation of Berlin post-1989 in both English and German; yet apart from a number of contributions by historians, little published work has addressed the politics of image making and the staging of the built environment through place marketing. The aim of the book is thus to explore the relationships between place marketing, the politics of urban development and the spatial politics of identity and memory construction in reunified Berlin – ‘the interplay between the physical stuff of planners and architects and the social experience and outlooks of image makers and their audiences’ (Bass Warner and Vale, 2001, p. xiii).

What Can We Learn from Berlin?

If Berlin was a particularly notable example of the ideal-typical state socialist city, it is now rapidly converting into what many would see as an ideal-typical version of an advanced capitalist city. (Harloe, 1996, p. 20)

Berlin in the early 1990s was too much in flux, too sui generis to fit neatly into existing theories of urban political economy, or to offer ready comparison to other cities for the benefit of theory building. (Strom, 2001, p. 1)

The question of the uniqueness or representativeness of Berlin has to be addressed from the outset: is Berlin a unique, atypical or extreme case, or can it be considered representative of urban processes and trends witnessed in other cities in Europe and elsewhere? Can we learn anything from Berlin which may contribute to theoretical developments in urban research? Single case studies are commonly criticized, in social sciences, for not being conducive to the possibility of generalization, despite the fact that formal generalization is only one amongst different methods of scientific enquiry through which people can gain and accumulate knowledge (Flyvbjerg, 2006). Nowhere does it hold truer than in the field of urban studies, where the key challenge for researchers is to ‘balance the peculiarities of place with an understanding of the generalizability of the processes observed’ (Latham, 2006a, p. 88). If the objective is to achieve the greatest possible amount of information on a given phenomenon – e.g. the role of place marketing and the politics of imaging in contemporary urban governance – then the choice of ‘atypical’ or ‘extreme’ cases is appropriate, as they ‘they activate more actors and more basic mechanisms in the situation studied’ (Flyvbjerg, 2006, p. 229).

Berlin after reunification can, in some way, be considered an ‘atypical’ or ‘extreme’ case according to Flyvbjerg's terminology: atypical because of its specific, peculiar history as a divided city in a divided country; extreme because of the intensity of the urban restructuring processes which unfolded over a short period of time post- 1989. The acceleration of history represented by the Fall of the Wall and the sudden absorption of East Germany into a capitalist democracy has brutally confronted the city with the economic, social and political challenges faced by other Western cities over several decades. A closer look at Berlin in the 1990s and 2000s is a particularly illuminating exercise for urban scholarship, ‘as it offers an excellent laboratory in which to study the central question of urban political economy: who, or what, determines the course of urban development’ (Strom, 2001, pp. 1–2)?

It is precisely because of the atypical and extreme situation of the city that a flurry of practices of place marketing and urban imaging emerged with a visibility and intensity rarely witnessed in other (European) cities, as part of the transformation of urban governance in reunified Berlin. In order to support the city's transformation into an invoked ‘European metropolis’, local policy-makers had to break with the negative images associated with the city's tormented past, reinvent and transmit a new image of the city to three main target groups: potential tourists, visitors and investors; Germans throughout the Federal Republic; and the Berliners themselves. The atypical and extreme situation of reunified Berlin has consequently acted as a ‘magnifier’ which makes the city a particularly salient case for making a contribution to theoretical debates on th...