![]()

1 Introduction

Interests of the most varied kind are bound up with those vast territories, hitherto so little known, which are comprised under the general denomination of Central Asia. The historian knows this to have been once the trystingplace of the numerous powerful hordes of nomadic races, who penetrated into the very heart of Europe, spreading ruin and devastation like a deluge; the geographer knows this region as the one that is still the most imperfectly represented on the map, where rivers, mountains, and cities can only be traced in vague outlines; the ethnologist recalls to his mind the group of Turanian peoples, together with indistinct ideas connected with them; and lastly, the politician perhaps looks forward to the collision that may take place between the two greatest powers on earth – the one by sea, and the other by land.

(von Hellwald 1874: ix)

The self-referred ‘Austrian military author’ Friedrich von Hellwald’s musings on Central Asia point simultaneously to the region’s obscurity and importance. Historically and as a discrete geographic region, Central Asia has often disappeared, submerged into bigger political and geographic areas. In 1994, a historical study of Central Asia commissioned by UNESCO (Dani and Masson 1992:19) acknowledged that ‘the role and importance of the various peoples of Central Asia are often inadequately represented in university courses, to say nothing of school textbooks’. In another author’s view, the area seemed to be simply receding out of view altogether until very recently, falling into a sort of geographical black hole ‘between disciplinary cracks’ (Gross 1992: 17). In the same year, André Gunder Frank (1992) was also to refer to the ‘black hole’ of Central Asia. As John Schoeberlein (2002: 4) writes, however, we do not need to be ‘among those who hope for things to get worse so that others will recognize the importance of this region’.

The endurance of a romantic, dangerous and arcane image of Central Asia may stem partly from a phenomenon that Edward Said (2003: 55) noted of the Middle East, namely that people are ‘not quite ignorant, not quite informed’. When informed, furthermore, their image is often reliant on popular media, which paints the region either as a place of swashbuckling heroes or terrorists, from the Great Game to interesting plots for James Bond movies, the BBC Series Spooks or the 20th Century Fox Network Series 24 (Heathershaw and Megoran 2011), or even as a site of hilarity, including Turkmenistan’s late President Saparmurat Niyazov and, most recently and importantly, Sasha Baron Cohen’s invention of Borat (Saunders 2010). In Gunder Frank’s (1992:4) terms it ‘makes no sense to regard “Central” (or “Inner”) Asia and its many different peoples as somehow all different from the rest of the world then and now. There was and is unity in diversity, and Central Asia was not apart from but constituted the core of this reality of human history and existence’. This normalcy is juxtaposed to so many of the received wisdoms and stereotypes we have today. Seasoned travellers to Central Asia will remark, often somewhat incredulously, that there were no militant Islamic societies. There were no nomads of the bygone era. There were certainly no Borats.

This fluctuation in the region’s prominence and sometimes its very existence is partly on account of the region’s geography. As a landlocked region, Central Asia is open to the influence of its neighbours, particularly when those neighbours at various times have been empires or great powers. The Persians, Turks, Greeks, Arabs, Chinese and Russians have all encroached on and transformed this region. At the same time, the unique features of the steppe (Sinor 1990) and its position on a frontier with these great powers (Barfield 1989; Grousset 2005) has nevertheless facilitated, and even compelled, the rise of its own strong indigenous rulers, notably those associated with the great Turkic and Mongol empires. The most recent instance of Central Asia’s reappearance has been after the collapse of communism in 1991.

This book addresses the contemporary period and it takes as its object of study the five ex-Soviet republics of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. This is not everyone’s idea of Central Asia. Many take Central Asia to be a far broader expanse that is more reflective of the area covered by a territory, often referred to in the English language as Inner Asia or Central Eurasia. Such a large expanse, therefore, would also take in Turkistan (east and west), Manchuria, Inner and Outer Mongolia and Tibet. A Central Eurasian perspective would also be likely to include parts of southern Siberia, northeastern Iran and northern Afghanistan. But still it can be argued that in contemporary usage the Central Asian, Russian and English understandings of the term more often than not refer to the five independent republics (Akiner 1998).

The post-Soviet focus in this book is further dictated by the author’s own interests and background. While a diverse set of themes are studied, the book’s focus is on the region’s broader political transformation since 1991. To locate ‘the political’ in the region, the book traces its history, identity, institutions, economics and its wider place in the world. It does so not chronologically but thematically, and for each of these related themes it asks a set of questions that have dominated their discussion of late. The isolation of these five republics for a study of post-Soviet change is further justified by the enormous influence the ‘intertwined Russian, Soviet, and Marxist transformations’ continue to exert on these countries’ early independence trajectories and how Soviet legacies go to the heart of the modern identity of various Central Asian peoples ‘from the semidesert environments of western Uzbekistan to the lush valleys of the Pamir Mountains shared by Tajiks and Kyrgyz, to say nothing of the cosmopolitan settings of Almaty and Tashkent’ (Sahadeo and Zanca 2007:9). Politically, the region has remained very much post-Soviet.

Russian influence on the region is, in historical terms, a recent phenomenon. This is, after all, ‘a “Turko-Persian” cultural world’ (Golden 2011). The term ‘Turkmen’ specifically referring to Turkic tribes in Central Asia who had converted to Islam, was first noted in the tenth century (Bartol’d 1968; Saray 1989; Edgar 2004). Similarly, the great Russian orientalist, academician Vasilij V. Bartol’d (1958) referred to how the word ‘Tajik’ was first recorded in the literature on Central Asia by the historian Bayhaqi who related how he had overheard a senior Iranian so describing his nationality in conversation with Mas’ud of Ghazni in 1039. The historical consensus appears that when invading Muslim Arabs and their Persian-speaking allies arrived in Central Asia by the seventh century AD they encountered nomads on the steppes north of the Syr, who, while then predominantly Turkic Darya became a mixed population ‘using Eastern Iranian languages as the medium of cultural and official communication, and dominated successively by a mixed Sasanian, Hephthalite and Turkic aristocracy’ (Bergne 2007: 5); in short, ‘in the ancient period, the nomadic peoples of the steppe were predominantly Iranian’ (Levi 2007: 18). The majority of Tajiks would come to speak a Western Iranian language (Persian, i.e. the language of Fars, a minority speaking Eastern Iranian languages of Yaghnob and the various Pamiri), the remaining Central Asians, Turkic languages.

After Islam had taken root, a dynasty of local governors, known as the Samanids, established a strong local political organization owing only nominal allegiance to the distant Abbasid caliphate of Baghdad. For the following thousand years the original Pre-Islamic Central Asian population would be either driven from the region or governed and gradually assimilated by a succession of invaders, including numerous Turkic peoples, such as those led by their dynasties, the Karakhanids (who overthrew the Samanids) and Seljuqs. Still other Turkic tribes arrived, intermingled and fought with the Mongol invaders in the thirteenth century (Morgan 1990) and, finally, arriving in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, as the confederation that became known as the Uzbeks (Allworth 1990). Russian traveller Khanykov noted that the Uzbeks by the middle of the nineteenth century were already the dominant group in the area. If Turkic speakers ethnically came to dominate, the use of Persian, partly as a result of surviving interaction with the main area of today’s Iran, continued to survive in government and social life, especially in Samarkand and Bukhara (Bergne 2007).

Within this ethno-linguistic mix, the fate of the category ‘Sart’ is illuminating (Schoeberlein 1994). At the time of his research Bartol’d (1997) noted that ‘Sart’ had come to mean ‘an Uzbekized urban Tajik’. But, as Alisher Ilkhamov (2004) notes, this traditional image did not accord with the Soviet ethnographic and socialist project, the relatively poorer rural Uzbeks conforming more neatly than the more prosperous urbanized Sarts. Sart was thus dropped in favour of Uzbek. Paul Bergne (2007: 9) elaborates how within ‘this composite “Sart” nationality were as yet unassimilated representatives of both Turkic and Tajik groups. On the Turkic side were Kipchaks, “Turks”, Kyrgyz and Kara Kyrgyz (up to the 20th century the Russian names for Kazakhs and Kyrgyz respectively), Karakalpaks, Turkmen people, Uzbeks, etc., many of whom still lived nomadic or seminomadic lives’. In the Soviets’ further attempts to categorize ethno-linguistic groups, therefore, they were also faced with the challenge of differentiating between Kazakh and Kyrgyz. During the 1924–36 national territorial delimitation process, in which the five selected ethno-linguistic groups of the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tajiks, Turkmen and Uzbeks were given their own national republics, a Soviet Central Asian space was born, and the borders of each of these Soviet Socialist Republics became those of the newly independent five ‘-stans’. Central Asia’s ‘catapult to independence’ (Olcott 1992) serves as a pivotal event, a critical juncture for all sorts of related developments that now place the five countries as independent actors.

Contemporary Central Asia in historical and global perspective

Emerging from this Soviet obscurity, authors have asked, are the five ‘-stans’ ‘one or many?’ (Gleason 1997). The answer is not simple because the five Central Asian countries share obvious commonalities as well as stark differences which push them as much apart (Bohr 2004; Suyunbaev 2010) as together (Gleason 1997; Tolipov 2006). The common historico-cultural threads just outlined, whose complexity and constant flux undermine regional stereotypes, can be as common in the degree of diversity as in their uniformity. At the same time Central Asia’s still recent emergence from Soviet rule has also left a number of what might be termed specifically Soviet legacies in all five states (Rakowska-Harmstone 1994). These Soviet legacies include: initial international isolation (both from the capitalist (Kaser 1992) and Muslim worlds (Khalid 2007c)); a politicized ‘strong-weak’ state (McMann 2004); a largely resource-based and therefore skewed economic development (Kandiyoti 2007); environmental degradation (Sievers 2003) that had resulted from Soviet gargantuan projects of modernity involving, for example, nuclear testing (Semey, Kazakhstan), river diversion with the (desiccation of the Aral Sea (Weinthal 2002) and intensive crop irrigation (Virgin Lands, Kazakhstan)); despite intensive Russification and Slav settlement during the Soviet period the emergence also in early independence of cultural titular superior status in the context of multi-ethnic states (especially Kazakhstan (Dave 2007), Kyrgyz Republic (Huskey 1997), Tajikistan (Akbarzadeh 1996)) with often a large second ethnic group (e.g. Uzbeks (and Russians)) in the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajiks in Uzbekistan or Russians in Kazakhstan (Bremmer and Welt 1995); and, awkward, either porous or potentially irredentist borders (particularly the enclaves in the Ferghana Valley and the Russian-Kazakh border for the former).

Legacies, Soviet or preceding, create challenges in the independence period. These include: consolidating new statehood and civic identities, while allowing for the growth of national cultures that were formerly developed but also oppressed; navigating from a highly controlling political system in which the Communist Party monopolized both state and regime, to one that provides at a minimum a system seen to deliver on its promises in a transparent way regulated by a fair and accountable set of rules; diversifying the economy so as to reduce these countries’ great power dependencies on global and volatile commodity prices while ensuring the continued livelihoods of those employed in agriculture and rural areas, with a view also to reducing overall poverty levels; and, establishing their independent foreign policies to reflect their worldview and pragmatic national interests. From an everyday perspective, in short, providing a new political container which enables the ordinary Central Asian to feel a sense of belonging and security, and lead a just and decent way of living is no easy matter when the various ethnic, cultural, religious and political priorities of each of the republics must be considered.

These challenges are not unique to Central Asia but the combination of pre-Soviet heritage, Soviet experience and geography offers a unique set of tools and a unique set of emerging outcomes. Specialists in political theory or comparative politics may enquire why Central Asia may provide an intriguing example alongside other regions. Those who already know the region need no persuading. While exciting, however, the beguiling and romantic nature of the region is not sufficient reason in itself for anyone to write thematically about it. Central Asia is particularly interesting as its evolution arises partly from its hugely diverse set of past and current influences. The compression of time and space that occurred again with Soviet collapse, when, almost by surprise (Yurchak 2006), peoples seemed to be again asked overnight to get used to a new set of rulers and ways of governing and existence means there is much to discuss that is interesting in political terms. In determining what makes this region what it is, it is necessary to consider, for example, that it still had a substantial nomadic population as recently as the beginning of the twentieth century and that the Soviet developmental project, that simultaneously aimed to sedentarize, collectivize and make literate the entire region in the fastest speed undertaken by any state modernization project to date. Attempting to further an in-depth understanding of any region is worthwhile, since it increases our critical faculties for assessing often Eurocentric methods and methodologies. Central Asia has and continues to be a laboratory for developmental projects; some gains have been made, but a great many have suffered and continue to suffer.

Various defining features of an early independent Central Asia are already emerging. The Soviet Union was called ‘the Second World’ and independent Central Asian republics continue to distinguish themselves from a Third World country (including in juxtaposition to their neighbour Afghanistan). But what does a cursory examination of the evidence suggest? Central Asian republics rank among the most corrupt nations of the world. They are also less free than other regions, comparable to some African countries (Freedom House Index 2011). They do, however, rank generally higher on indexes of state capacity, than, say, African states (Beissinger and Crawford 2002), having emerged on independence, as we shall see, with a partial statehood developed under the constraints of Soviet federalism. Economically, they emerged from the Soviet era with colonialtype structures and lopsided development that made them primarily raw material producers, with some now sitting on enormous natural resource wealth. Societies emerging from Soviet rule were highly educated and literate. Economically their GDP per head income levels vary from those of mid- to lower-level income countries. According to the World Bank (2011), poverty levels vary significantly, the opposite poles being the poorest Tajikistan and the fastest growing economy of Kazakhstan which has registered a double digit growth rate since 2001 (Cummings 2005). But even in the latter, income levels among the population remain hugely varied. Overall, the indicators are mixed and do not slot the region comfortably into either the ‘first’ or ‘third’ worlds.

In terms of political regime, the five have flirted with liberalization but the landscape remains on the whole an authoritarian one. In terms of ethnicity and ethnic belonging, we have examples of distinctly multi-ethnic states juxtaposed with more mono-ethnic ones. With the important and tragic exceptions of Tajikistan (1992–7), Uzbekistan (2005) and the Kyrgyz Republic (2002, 2010), Central Asia has been relatively more stable than comparable post-colonial countries in the immediate aftermath of imperial collapse.

The book’s themes and organization

Understanding why Central Asia has come to hold these political associations is the subject of this book. In the following chapters six key themes that have served to strengthen our understanding of newly independent Central Asia are discussed: its regional classifications; its past; its culture, beliefs and identity; its politics; its economic transformation; its security and wider international relations. These six areas help answer some of the political questions that independence has brought. For example, how has independence changed the way the region’s borders are drawn and experienced? How has it changed the way leaders and societies evaluate their pasts? How has it changed the way societies are governed? How has the new political container changed the way economies are managed and accessed by the outside world? And how are these new entities being secured, both in providing positive sovereignty (the state providing sufficient goods and services) and negative sovereignty (the securing of borders to prevent penetration from the outside world)?

Chapter 2, devoted to a discussion of what we understand by the geography of Central Asia, shows how my study concerns the five post-Soviet Central Asian republics. I am mindful that this definition of Central Asia is subject to reshaping. That reshaping, it is argued later, is primarily concerned with security interests, particularly in light of the challenges of Afghanistan and the growing influence of the region’s two great powers, China and Russia. But it is also a function of how actors, domestic and external, attribute meaning to their region. While in the Soviet period the five ‘-stans’ had been known as ‘Middle Asia and Kazakhstan’, in 1993 leaders decided to rename themselves as Central Asia. This decision in itself is interesting. Rather than expressing a strong regional identity, it reflected an identity by default. The institutionalization of the region, or regionalism, has been largely absent from the Central Asian landscape. A larger ‘geopolitical framework’ (Banuazizi and Weiner 1994), in which contiguous states are included is also, in part, a response to the observation that Central Asian states have been better at co-operating when outside powers have been involved. The chapter also looks at the various debates that surround the term ‘heartland’ and the degree to which we may comfortably use this term.

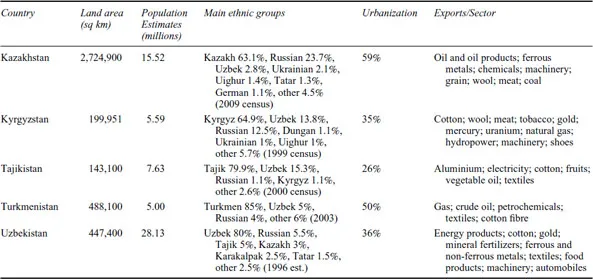

Table 1.1 General indicators

Source: Compiled from: Nations in Transit (2011); EIU Country Reports (2010 and 2011); National Census Results (2009); The World Factbook, Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency (2011) and CIA (2011).

As a bridge to Chapter 3, questions are asked...