![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as well as if a manor of thy friend's or of thine own were; any man's death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bells tolls; it tolls for thee.

(John Donne, 1624)

Design is a powerful tool for integrating knowledge across disciplines. Rural design is a new discipline that currently does not exist in any academic program in the United States or around the world. It is a methodology to bring design as a problem-solving process to rural regions to nurture human ingenuity, entrepreneurship, creativity, and innovation. It provides an opportunity to reflect upon and integrate human and natural systems into a viable, sustainable design process to improve quality of life. Never has the time been more opportune for such an approach, nor is it more needed.

On June 8, 2002, fourteen inches of rain fell on the rural City of Roseau in northwestern Minnesota near the Canadian border. The damage from the deluge was enormous, resulting in destruction of downtown businesses and private residences. Ninety percent of the 150 commercial buildings and most of the public buildings and public utilities suffered major damage. More than fifty homes needed to be demolished and replaced – many owned by low-income families.

The city was overwhelmed by the reconstruction process because there was no plan or consensus about how to proceed. Working with the University of Minnesota's Center for Rural Design, the city's leadership and concerned citizens developed a community-based reconstruction vision plan for rebuilding the community that holistically looked at land issues, demographics, economics, recreation, and the qualities of life desired by the residents. According to Todd Peterson, Roseau's Community Development Director, ‘The City of Roseau could not have achieved the success in reconstructing the community as it did after the flood without having public buy-in of the reconstruction vision plan.’ As evidenced in Roseau, rural design offers a new approach to meeting the needs and challenges rural communities face as they manage change or respond to needs in a time of crisis.

Rural design is an emerging design discipline that was started at the University of Minnesota in 1997 when I founded the Center for Rural Design (CRD). Since that time the CRD has been involved with a number of projects that impact quality of life in rural areas, primarily in the State of Minnesota. Yet we have learned that the principles of rural design can be applied anywhere. The intent of this book is to inform readers about rural design as a new design discipline – what it is and what it can do for rural communities worldwide.

I am a designer who was trained as an architect, taught architectural design, and has practiced the profession as a registered architect for a number of years. It has been an experiential journey of discovery and everything in this book reflects what I have learned about rural people, rural issues, rural landscapes, rural planning, and rural architecture. There are other design and research disciplines with different points of view from a cultural, social, economic, and environmental perspective, however most respond from an urban point of view. Landscape architecture may have the strongest connection to rural design because it is so closely linked with cultural and natural landscapes and their ecosystems.

The book is intended to be an introduction to rural design and an outline of multidisciplinary and evidence-based research that responds to the variety of rural issues that need to be resolved. Design can integrate knowledge across disciplines, and while not directly engaged in research, designers can translate and apply research knowledge to the design process – helping bridge the gap between science and society.

This issue of applied research through design is not well understood by many funding organizations that support scientific research regarding agriculture and rural environments. To them, research is discipline-oriented and focused on subjects that end up in scientific journals to inform other researchers. This book is not a traditional research-oriented textbook. Rather it is about design thinking as a means to utilize research knowledge and translate that evidence through the rural design process to benefit rural society. With the world changing so rapidly, design thinking and rural design, as a community-based problem-solving process, is becoming more and more important as a means to manage and shape rural futures.

Rural design brings the methodology of design to rural issues. Through that process, other academic disciplines involved with agricultural, cultural, and natural landscapes have embraced the concept. Rural design can assist academia in making connections holistically and systemically, and through its practice contribute to rural economic development, environmental protection, and improved quality of life.

Rural change

Over the past fifty years, rural regions in North America and worldwide have undergone enormous changes impacting quality of rural life and their economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Critical global issues, such as population increase, climate change, renewable energy, water resources, food supply, and health will further impact rural policies for years to come. So, how do rural people deal with these issues so they can manage change while maintaining and improving their quality of life?

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA ERS, 2008) rural regions in the United States contain 21% of the population and comprise 97% of its land area. In Canada, rural areas are 99% of the land area and contain 20% of its population (Statistics Canada, 2006). From these statistics you can surmise that rural areas of North America have a very low population density per square kilometer.

In the European Union, 56% of the population is living in rural areas that encompass 91% of the land area. It has a much higher rural density than North America, largely due to economic and cultural support for agriculture and to enhance tourism (ENRD, 2010). South Asia, on the other hand, has approximately 70% of its population living in rural areas, of which 69% is suitable for agriculture. It is one of the rural regions in the world with the highest density of population per square kilometer; and typical of developing regions where the rural population has the highest levels of poverty, with farming systems that are among the most susceptible to climate change and economic problems (Weatherhogg et al., 2001).

Rural issues vary a great deal around the world, and while this book illustrates the principles of rural design through the work of the CRD in the Midwest region, design thinking – integrating knowledge across disciplines to solve difficult social, technological, and economic problems – is a process that can be applied worldwide.

Rural design: a new way of design thinking

Rural design, as a new interdisciplinary design discipline, can help rural communities manage change through the lens of spatial arrangement, and in the process provide a link between science and society to improve rural quality of life. Rural design and urban design are similar in that both embrace quality of life. Rural design is, however, fundamentally different from urban design in seeking to understand and embody the unique characteristics of open landscapes and ecosystems where buildings and towns are components of the landscape, rather than defining infrastructure and public space – as in urban design.

Urban planning deals with public policy and statutory issues affecting the public realm and use of the land. Urban design requires an understanding of urban economics, political economy, and social theory and mainly deals with the way public places and the public realm are experienced and used. A model example of urban design is the building design that Louis Sullivan created for a bank in downtown Owatonna, Minnesota constructed in 1908 (Figure 1.1). Here the bank building (perhaps the finest example of place-making architecture in America) is clearly following the property line, shaping the edge of the street, and flanking and framing a corner of the central town park in this beautiful rural city on the prairie. Larry Millett in his book, The Curve of the Arch, describes how the park was the focal point of the downtown and: ‘It was to this pleasant little park that Sullivan may well have come one day, probably in early October 1906, to create the outlines of a masterpiece’ (Millett, 1985). To me this wonderful building is the epitome of how urban design and urban architecture shapes the public realm to define city.

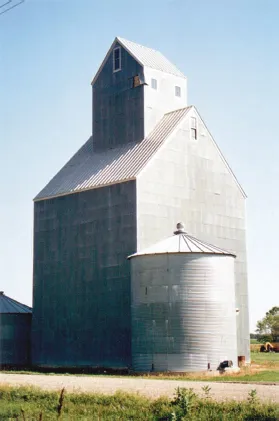

Rural design, on the other hand, is the spatial arrangement of rural landscapes and the buildings within them. It is best exemplified by thinking of buildings and rural towns as objects within the larger open landscape. Like the simple wood grain elevator (Figure 1.2) standing tall in the open prairie of northwestern Minnesota as an icon for agriculture; or this modest wood, metal roofed harvest shelter (Figure 1.3) in a vineyard in Napa Valley, California almost hidden in the surrounding fields of grape vines. In both situations the buildings are clearly isolated as objects in a field just as the field is one of many in the rolling prairie or valleys of the open landscape.

1.1

A bank in the rural town of Owatonna, Minnesota designed by Louis Sullivan. Constructed in 1918, it is an example of urban architecture shaping public space and public realm. Here the building flanks the downtown Central Park creating a beautiful and timeless work of architecture and urban design, with form following function, climate, and place.

1.2

Tall grain elevators in rural towns throughout the Midwest are as common as church steeples, reflecting the agrarian economy of the land.

Rural character and definitions of rural places have scales and relationships to the natural and cultivated environments that are entirely different from those that urban design has in its relationship to urban environments. This difference requires rural designers to have an understanding of the cultural landscape as well as the natural landscape of the rural region within which they are working. Cultural landscape has been defined by an ethno-ecologist as ‘the dynamic physical relationships, processes and linkages between societies and environments’ and ‘how societies perceive the environment and the values, institutions, technologies and political interests it places on it that result in planning and management goals and objectives’ (Davidson-Hunt, 2003).

1.3

The vineyard shelter in Napa Valley, California rises like a hill out of the field, echoing the hills behind. It is a working building in the agricultural landscape reflecting functional purpose and fit with rural character.

Human and natural systems are dynamic and engaged in continuous cycles of mutual influence and response. Rural design provides a foundation from which to holistically connect these and other rural issues by nurturing new thinking and collaborative problem solving. As a discipline, rural design can address contemporary problems while continuing to evolve as research-based evidence is accumulated. The principles and methodologies of rural design can be utilized anywhere because it is by definition rooted in the nature and culture of place.

The assets of a community are often hidden to its citizens, and rural design provides a civic engagement process and geo-spatial mapping that uses community workshops to review alternative scenarios to see the likely results of different decisions. The guiding ethic of rural design is not to impose a vision or solution on a community, but to:

• Provide the tools, information, and support that rural communities need to address their problems;

• Help rural citizens manage change caused by economic, cultural, or environmental reasons;

• Assist in connecting the dots to create synergy for environmental wellbeing, rural prosperity, and quality of life;

• Clearly envision and help citizens achieve the quality of rural future for their community that they deserve.

Designers share a common trait in that we love to solve problems and create solutions. Problems excite us, and rural regions around the world have many problems. This book, in addition to being an introduction to the emerging new design discipline of rural design, also reflects my architectural background and discovery of the radical changes taking place in rural areas of North America and how I grew to realize that a new rural design discipline dedicated to resolving rural issues could have a positive impact on those changes.

I first started to write about the architecture of agriculture and the design of working buildings in rural landscapes with a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts. That effort was based on my work as a professional architect involved in the design of interpretive facilities involving animals. These included a new zoo in Minnesota, the first northern climate zoo in the world designed to be open year-round, exhibiting animals in their natural habitat; several animal interpretive centers for both domestic and wild animals; and several animal agriculture research facilities at universities in different parts of the country. Simultaneously I was teaching architectural design in the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of Minnesota and had organized a number of studio projects that involved students in the design of animal agriculture facilities and multifunctional educational buildings located in small towns in rural Minnesota.

The studio projects included presentations by academicians and experts involved in animal agriculture, who discussed rural issues and the profound changes that were taking place. I was aware of the poor quality of design in most contemporary farm buildings and other structures related to agriculture – however, I was not fully aware of the influences that created those buildings. We learned that because of economic conditions, there were fewer farmers and larger farms, resulting in the construction of large livestock buildings that all looked the same with many more animals than found in traditional historic barns. And we learned that these changing economic and social conditions were negatively impacting rural quality of life.

While researching historic barns, other agricultural buildings, and specialized contemporary buildings constructed for dairy, swine, and poultry, I began to realize that the is...