![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

When in 1907 the well-known nuclear physicist Lise Meitner left Vienna as a young Ph.D. to further her education at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-University in Berlin, she was on her arrival treated very differently than her male colleagues because at that time women were not yet officially admitted as students in any university in Prussia. The head of the university’s Chemistry Institute, and winner of the Nobel Prize, Professor Emil Hermann Fischer was known for not allowing female students in his institute rooms or in his lectures. When attending lectures, the studious Austrian had to hide in the space beneath the staggered wooden benches of the lecture hall, as it had been made clear to her that she was not wanted on the premises. She was initially also denied access to the chemistry laboratory, though Fischer eventually agreed on the condition that she would stay in the cellar of the Institute and never set foot in the upper floors. It was on such a condition that Meitner began her work in Berlin in a former woodworking workshop in the cellar of the Chemistry Institute, with a separate entrance and without a washroom. Although Max Planck, who at that time was teaching a course in Berlin on theoretical physics, missed no opportunity to fulminate against ‘mental Amazons’, Meitner was finally able to convince the scientist of her abilities. He allowed her to attend his lectures, and in 1912 he even appointed her as his first university assistant.1

But not all male scientists allowed themselves to be impressed by the young woman’s performance. At the beginning of her career, Meitner, an ambitious researcher, had already published a number of articles under the name L. Meitner. Impressed by the articles, the publisher of the German Brockhaus Encyclopaedia asked Meitner to write an entry on radio-activity. Since she signed the reply to Brockhaus with her full name, it then became apparent that she was a woman. As Meitner recalled, the publisher replied stating he would never publish an article written by a woman.2

For the purposes of the present study, it is not necessary to dig deeper into Meitner’s biography. What I want to emphasize in this context are the visual, spatial and architectural dimensions of the means by which she was subordinated. In this example, these means were directly and demonstratively represented by the lecture halls and laboratories of the prestigious university, which were rooms and structures accessible only to certain groups and from which other groups – in this case all women regardless of their academic qualifications – were explicitly excluded. At that time this form of gender separation was common in many buildings, private homes, religious and secular institutions, hospitals, military buildings, and sanitary facilities. For example, British women in the nineteenth century who wanted to listen to political debates in the old House of Commons were subjected to similar circumstances as those Meitner had encountered. Without a voice and unseen, they had to hide in order to partake in the knowledge of men. They were expected to stay seated, hidden away in an attic room of the building, and follow the discussions of the men below through ventilator openings in the ceiling.3 Not only were the women in both cases told that if at all possible they should not be seen in the building, but also they had to assume a degrading bodily position that demonstrated to them physically that they were on forbidden territory.

However, measures with the purpose of hiding certain groups, in particular women, from the sight of others or excluding them altogether were not enacted exclusively for special state buildings. They were quite common and widely accepted, mainly in the representative architecture of the time which was characterized by a strikingly accentuated allocation of space.4 In such buildings the planned use of space sometimes indicates very strict social hierarchies and distinct gender differentiation. The staff were assigned their own servants’ entrances and hidden staircases, often separated according to gender, while the gentry claimed exclusive access through the magnificently designed main entrances. Sometimes the hierarchy of room allocation went so far that the servants were only allowed to move around in spaces that were not actual rooms, but spaces inside the walls. In many palaces, such as the Schönbrunn palace in Vienna, the thick walls concealed narrow, dark passages through which the servants had to squeeze in order to light the mighty tiled stoves from behind, without being seen by the gentry. Some rulers were extremely creative in maintaining the largest possible service staff without being exposed to their eyes and without having to allow them access to their private rooms. It is known that King Ludwig II of Bavaria had such an aversion to his servants that his Linderhof and Herrenchiemsee palaces each had a so-called magic table (see Figure 1.1): the dining table could be lowered to a floor below where the food was laid out by the servants so that the king did not have to come face to face with them.5

In Western culture today social and gender-specific room divisions are usually less obvious, but even in recent architecture history there are several examples of rooms which for one reason or another are assigned to one sex only, are off limits to the other sex or are divided along gender lines. Many of these rooms also serve the purpose of strengthening the social practices and hierarchies of the sexes in those places. This is particularly obvious in those religious buildings where the practiced rituals and traditions subordinate one sex. Thus, Roman Catholic women have not been allowed as a rule the same rights as men to use all the rooms in a church. Usually, even nuns are forbidden to enter the area beyond the rood screen while altar boys, deacons and priests are allowed to enter that area to celebrate the mass. Often, women have not even been allowed to look at the high altar and the presbytery, which were screened from view over the entire width of the sanctuary. The only time women got access to the area was as charwomen, cleaning the space after the service.6

1.1 ‘Magic table’, Herrenchiemsee, about 1885

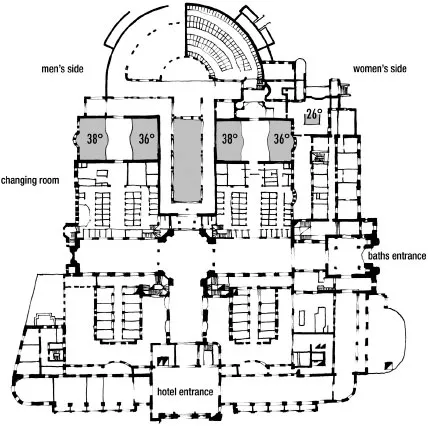

1.2 Floorplan, Geliert Baths, Budapest (Architect: Hegedüs, Sebestieyen, Sterk)

Ironically, sometimes buildings to which women were denied access were adorned with female bodies. An example from the modern age with a commercial use are the Gellert Baths in Budapest, which often feature in the city’s tourism brochures and postcards. The building, designed by Armin Hegedüs, Artur Sebestieyen and Izidor Sterk, has a floorplan that is divided into two almost identical halves connected in the middle by a pool to which both sexes have access (see Figure 1.2). When it opened in 1911, as a combination of spa and hotel, it attracted an international clientele from the upper social classes. The exterior facade of the complex has a monumental design, while in the interior glossy tiles, mosaics and frescoes were used to give the facility an appearance that was as rich and ostentatious as possible. The indoor pools, divided according to sex, originally had identical layouts, each with two thermal baths and two steam baths. However, on closer inspection, it becomes apparent that the side reserved for men is much more richly ornamented than the side for women. For that reason, tourist guidebooks and postcards always only show the interior of the men’s side, and for advertising purposes women are usually photographed in the male rooms. It can be assumed that female users of the day never learned that the rooms reserved for men were decorated much more elaborately and expensively. Even today, this is only apparent from the photographs that hang in the long hallways of the baths. But excluding women from certain spaces and using their bodies as alluring embellishment are only two possible strategies to express sexual hierarchies in architecture.

The architectural construction of gender

The above examples indicate that social standards sometimes manifest themselves in architecture, and that architecture may also contribute to strengthening social conceptions and behaviour patterns. As Bill Hillier notes:

At the very least … a building is both a physical and spatial transformation of the situation that existed before the building was built. Each aspect of this transformation, the physical and the spatial, already has … a social value, in that the physical form of the building may be given further significance by the shaping and decoration of elements, and the spatial form may be made more complex, by conceptual or physical distinctions, to provide a spatial patterning of activities and relationships.7

This argument – that social structures are in the last analysis spatial – has in fact been evident in many theories of architecture since the publication of Henri Lefebvre’s La production de l’espace (1974) and Michel Foucault’s Surveiller et punir (1975).8

In defining the production of space, Lefebvre differentiates between spatial practice (how space is perceived), representations of space (how space is imagined or depicted) and representational spaces (the space we live in).9 The main argument of Lefebvre’s theory is that the entire social space is derived from the body and that all space has a social meaning. The social dimension is then not a contingent characteristic of certain kinds of spaces: everything is ontologically spatial. It follows that the borders between objects and the self are contingent. Space, as well as society, participates in constructing the limits of the self, but the self is also projected onto society and space.10

The mediating element between the self as a living reality and society’s spatial–architectural structures is the body. The argument that social and political power affect and are affected by the physical body was convincingly made by Foucault, who writes:

The body is also directly involved in a political field; power relations have an immediate hold upon it; they invest it, mark it, train it, torture it, force it to carry out tasks, to perform ceremonies, to emit signs … the body becomes a useful force only if it is both a productive body and a subjected body.11

As far as it is true that the body is a necessary element in the power structures of society, architecture can also be assigned an important role. That is why, apart from Foucault himself, many of his followers, such as Paul Rabinow and Richard Sennett, have shown examples of how architecture can contribute to disciplining.12

A third variant of French theory which has had a significant influence on studies of power, space and body comes from Pierre Bourdieu and his theory of rituals in the form of habitus.13 In Outline of a Theory of Practice, Bourdieu defined habitus as a generative system of ‘durable, transposable dispositions’ that emerges out of a relation to wider objective structures of the social world. As an internalized collection of durable dispositions to think, feel and act, habitus is, according to Bourdieu, like a ‘conductorless orchestration’ giving systematicity, coherence and consistency to an individual’s practices.14 Helen Hills, for example, has argued that Bourdieu’s notion of habitus is an essential factor in the constitution of gender roles and that it constructs different roles mainly through the material culture of space:

Space, the fundamental aspect of material culture, is … of central importance in constituting gender. It determines how men and women are brought together or kept apart; it participates in defining a sexual division of labour; its organization produces, reproduces and represents notions about sexuality and the body. Space determines and affects behaviour, just as the organization of space is produced by and in relation to behaviour.15

While Hills’s main point is valid, this particular statement illustrates some problems with the rhetoric of the ‘spatial turn’ in the social sciences. Occasionally in such writings space takes on almost mythical dimensions and becomes a social force. When Hills says that ‘space’ keeps men and women apart, she probably means that there is a spatial separation between men and women, either through distance or material (e.g. through non-spatial elements such as walls). Here space is nothing but another word for the coming together of, or separation between, men and women, and not the ‘force’ that has caused it. Hills argues further that space participates in defining the sexual division of labour, but this statement contributes little to the first statement, since she already claims that ...