![]()

| PART I |

| Theory and evidence |

![]()

1

What is an At Risk Mental State?

Most patients with schizophrenia go through a prodromal period in which they experience problems such as depression, sleeplessness, agitation, cognitive difficulties, and decline in social and vocational functioning. In addition, psychotic symptoms can be experienced at a subclinical level. Retrospectively, these features are recognised as prodromal to the outbreak of a first psychotic episode.

Many of the prodromal features are non-specific and cannot be used as a single predictor of an imminent psychosis. For instance, many first episodes are preceded by depression, but a depressed mood does not necessarily end in a psychotic state for most people who experience a depressed mood. For this reason, it has been very difficult to predict relapse and even more difficult to predict the transition to a first psychotic episode. To predict the transition to psychosis, the best strategy seems to be to follow up subjects at ultra-high risk for developing a first psychosis. The current international consensus differentiates ultra-high risk subjects into four groups (McGorry, Yung and Phillips, 2003; Miller et al., 2003; Yung et al., 2005); individuals in these groups have an ARMS:

1 a genetically endowed group with a schizotypal personality disorder or a first-degree relative with psychosis (genetic group);

2 subclinical psychotic symptoms of adequate intensity and low frequency (subthreshold frequency group);

3 subclinical psychotic symptoms of low intensity and relatively high frequency (subthreshold intensity group);

4 florid psychotic symptoms during less than seven days, which go into remission without an external intervention such as antipsychotic medication. This condition is also called brief limited intermittent psychotic symptoms (BLIPS).

In addition to the above-described criteria, there has to be impairment in social functioning as assessed with the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) (Goldman, Skodol and Lave, 1992), i.e. a SOFAS score of ≤ 50 in the past 12 months or longer, and/or a drop in the SOFAS score of 30 per cent for at least one month in the past year.

What is the incidence of psychosis in ARMS?

The transition rates from ARMS into a frank psychosis have a relatively wide range. Earlier studies reported relatively high transition rates (about 40 per cent; McGorry, Yung and Phillips, 2003; Miller et al., 2003), whereas more recent studies report more modest transition rates (7–20 per cent; Ruhrmann et al., 2010). Over the years, the transition rates in the Australian project have been declining, which the researchers attribute to an improved health-care system that detects ARMS subjects much earlier than previously, when subjects were already in a late prodromal stage (Yung et al., 2007). This offers a clinical advantage, because therapy may be more effective in an early prodromal state and can result in a reduction in the number of transitions. Another explanation for the lower transition rates might be the inclusion of a larger proportion of ‘false positives’ in the research sample. False positive means that the person is suspected of being at risk for developing a psychosis, but will never actually develop a first psychosis.

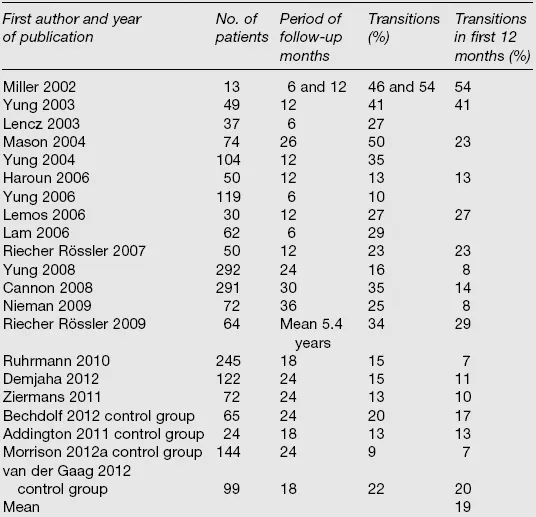

Table 1.1 shows the reported transition rates from studies (published 2002–2012). A recent meta-analysis showed 18 per cent transition after 6 months; 22 per cent after 1 year; 29 per cent after 2 years and 36 per cent after 3 years (Fusar-Poli et al., 2012).

Table 1.1 Transition rates in ultra-high risk studies

Prevalence and incidence of psychotic-like experiences

Psychotic features are not uncommon in the general population. Having one or more psychotic symptoms was found in 24.8 per cent (n = 5877) of the American population (Kendler, Gallagher, Abelson and Kessler, 1996), in 17.5 per cent (n = 7076) of the Dutch population (van Os, Hanssen, Bijl and Vollebergh, 2001) and in 17.5 per cent (n = 2548) of the German population (Spauwen, Krabbendam, Lieb, Wittchen and van Os, 2003). In a birth cohort, 25 per cent (n = 761) reported at least one psychotic symptom at age 26 years (Poulton et al., 2000). In an English–German–Italian study, in which hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations were also included, the percentage increased to 38.7 per cent (n = 13057) (Ohayon, 2000).

It is difficult to detect a rare disease in the general population. The incidence of subclinical psychotic symptoms is about 100 times as high in the population as the incidence of a psychotic disorder (Hanssen, Bak, Bijl, Vollebergh and van Os, 2005). In a population-based survey using the Dutch NEMESIS cohort (n = 7076), 18.1 per cent of the subjects had one or more self-reported psychotic symptoms, while 0.4 per cent had a non-affective psychotic disorder and 1.1 per cent had an affective psychotic disorder. After three years the group with one or more psychotic symptoms was symptom free in 84 per cent of the cases. Persistent psychotic symptoms (without meeting the diagnosis of a psychotic disorder) were present in 8 per cent of the cases, whereas another 8 per cent of the subjects had developed a more serious condition and was in need of treatment because of the psychotic symptoms.

In the common pathway to psychosis, psychological appraisal processes seem to play an important role. A negative emotional appraisal of the symptoms preceded the transition into psychosis (Hanssen et al., 2005). Furthermore, subclinical hallucinations have a higher incidence of developing into frank psychosis when the person develops secondary delusional beliefs and appraisals (Krabbendam et al., 2004).

In the NEMESIS study, self-rated symptoms were validated by professional judgement. In 37 per cent of the cases, the professionals judged the symptoms to be absent. It is important to be aware that self-assessment may result in an overrating of symptoms. However, the false positives, where the professional down-rated a self-reported symptom, still had a higher rate of developing psychosis (OR = 19.2) after three years. The true positives had, of course, the highest rate (OR = 77.1) (Bak et al., 2003).

Closing-in strategy

Since subclinical symptoms are highly prevalent in the general population and most of these symptoms remit spontaneously, preventive intervention is not really an option. Too many false-positive subjects, who will never develop psychosis, will be treated unnecessarily. To reduce the number of false positives, the sample that is assessed must be enriched.

Enrichment can be achieved by combining risk factors: the closing-in strategy. For example, the risk of developing psychosis within two years when a subject experiences one psychotic symptom is only 8 per cent; the risk of developing psychosis within two years when the subject has a family history of schizophrenia is only 1 per cent; however, the combined risk of these two variables for developing psychosis within two years is 25 per cent.

This increase in risk is also present in other risk factor combinations (van Os and Delespaul, 2005):

| Subclinical symptom with distress and/or help seeking | 14% |

| Subclinical symptom with depressed mood | 15% |

| Subclinical symptom with impaired social functioning | 16% |

| More than one subclinical symptom | 21% |

| More than one subclinical symptom with depressed mood | 40% |

A possibility is to screen a young and help-seeking population with a self-rating instrument and then perform the ‘gold standard’ CAARMS interview to detect the psychotic and the at-risk subpopulations. The ultra-high risk group is then composed of young people with an axis 1 disorder and psychotic-like experiences with some distress; this group will have a theoretical risk of transition within two years of 15–25 per cent.

What is the risk of psychosis in help-seeking ARMS subjects?

In a help-seeking population, 59.2 per cent of the patients remitted in one year; 13.5 per cent made the transition into frank psychosis and 27.3 per cent had persistent subclinical symptoms (Simon et al., 2009). Compared to the general population, the number of transitions has almost doubled and the number of patients with persistent subclinical positive symptoms has more than tripled. Over a two-year time frame, if an intervention could reduce the number of non-remitted patients from 40 to 20 per cent it would be regarded as a valuable intervention. When we take into account the costs of a transition, more modest results could also be cost-effective as schizophrenia is a very costly condition over a lifetime because of high admission costs and huge losses due to persistent vocational impairment and disability pensions.

Ethical issues

The main issue in preventive intervention is the number of people who are treated unnecessarily. This is especially true with non-perfect treatments (e.g. 50 per cent success rate) and adverse side effects (e.g. of antipsychotic medication). The minimum requirements are an identified risk population with a transition rate into psychosis of 25 per cent, and a 50 per cent reduction in transitions as a result of the intervention. In that case the number needed to treat is ten, which is considered to be acceptable. When the population/individual is seeking help themselves, then the objection of unnecessary treatment is no longer valid.

![]()

2

How to identify ARMS subjects?

Importance of identifying ARMS subjects

Many studies have shown the importance of the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) for the long-term prognosis in first episode psychosis patients (Drake, Haley, Akhtar and Lewis, 2000; Large, Nielssen, Slade and Harris, 2008; Larsen et al., 2011; Melle et al., 2008). Patients with a long DUP have more severe symptoms at first presentation, and long DUP may be associated with a reduced response to antipsychotic medication (Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman, 2005).

In previous studies assessing DUP, a wide range in median and mean DUP was found. Marshall and colleagues conducted a systematic review and found a mean DUP of 103 weeks, as assessed in 26 studies (Marshall et al., 2005). A more recent review reported a median DUP of 21.6 weeks, as assessed in 24 studies (Anderson, Fuhrer and Malla, 2010).

The Northwick Park Study reported that if things are not well managed in the early stages of psychosis, then deterioration continues until finally a crisis occurs, which frequently involves the police (Johnstone, Crow, Johnson and MacMillan, 1986). Floridly psychotic subjects may be admitted involuntarily. However, there is evidence that such admissions can lead to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Frame and Morrison, 2001; McGorry et al., 1991). During psychosis, subjects are often unable to work and become socially isolated. Patients often lack insight into their illness and may alienate family and friends. In retrospect, the period before the onset of frank psychosis is called the prodromal period and can last up to five years. Prospectively, this period is called the ARMS period, because not all subjects with an ARMS for developing psychosis will make the transition to psychosis.

In the ARMS period, subjects are often aware that something is wrong. They may be afraid of losing their mind. Subjects in the ARMS phase could say: ‘Sometimes I think I’m being followed – but I know this is unlikely’, whereas a psychotic patient may say: ‘I am being followed’. Obviously, it is easier to intervene if subjects still have illness insight and illness awareness. In addition, subjects with an ARMS may still maintain social contacts, work and/or education, although to a decreasing extent because of their symptoms. Intervening in the ARMS phase offers the opportunity to help subjects preserve their activities and thus avoid a decline in functioning. Furthermore, if subjects are already in care before their first psychotic episode and unfortunately do make the transition to psychosis, then they have a DUP of almost zero weeks.

Some argue that detecting ARMS subjects carries the risk of stigmatising these subjects and making them more worried than is necessary. In our experience, ARMS subjects do not feel stigmatised when their symptoms are discussed and when they are treated for their symptoms. Because of the closing-in strategy (see Chapter 1), subjects are seeking help and they are already worried. Offering treatment in the form of psycho-education and help with preserving their daily activities (work/schooling and social contacts) reduces catastrophic interpretations of extraordinary experiences and is usually not experienced as stigmatising.

Instruments

Over the years, several instruments have been developed to identify subjects with an ARMS for developing psychosis. The Structured Interview of Prodromal Syndromes with its rating scale, Scale of Prodromal Symptoms, was developed at Yale University (USA) by the group of McGlashan (Miller et al., 2003). This instrument is comparable but slightly different from the other widely used scale: the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental States (CAARMS). This latter instrument was developed in Australia (Yung et al., 2003) and is updated every few years based on latest scientific findings.

The CAARMS (version 3) is composed of seven sections:

1 Positive symptoms (four items)

2 Cognitive change attention/concentration (two items)

3 Emotional disturbance (three items)

4 Negative symptoms (three items)

5 Behavioural change (four items)

6 Motor/physical changes (four items)

7 General psychopathology (eight items).

The positive symptom items are currently the main items on the basis of which subjects are included in an ARMS sample. The four positive symptoms items are:

1.1 Unusual thought content

1.2 Non-bizarre ideas

1.3 Perceptual disturbance

1.4 Disorganised speech.

These items are scored with anchor points on intensity (0–6-point Likert scale) and frequency/duration (0–6-point Likert scale). Furthermore, dates of start and end of symptoms are annotated, as well as the level of distress (0–100) and relationship with drug use (0–2). The CAARMS can be found on the website related to this book. It is important to ascertain the combination of intensity and frequency/duration of the positive symptoms if a subject has attenuated positive symptoms, BLIPS, psychosis and/or is above or below the threshold symptoms (see case examples below).

In the 1960s Huber and Gross designed the Bonn Scale for the Assessment of Basic Symptoms (BSABS) on the basis of the primary symptoms of schizophrenia according to Bleuler (Bleuler, 1911). Basic symptoms are subtle, subjective, subclinical disturbances in cognitive, motoric and emotional functioning. Further analyses of basic symptoms resulted in a set of predictive criteria based on nine cognitive disturbances (BSABS-P) (Klosterkötter, Hellmich, Steinmeyer and Schültze-Lutter, 2001; Schültze-Lutter and Klosterkötter, 2002). The BSABS-P has predictive validity for a first psychotic episode over a period of ten years and may reflect the earliest signs and symptoms of a schizophrenic development.

More recently, the self-report Prodromal Questionnaire (PQ), was developed by Loewy and colleagues to screen for possible ARMS symptoms (Loewy, Bearden, Johnson, Raine and Cannon, 2005). If subjects score above a certain cut-off, a semi-structured interview, like the CAARMS, is recommended to ascertain whether subjects fulfil the ARMS criteria. Ising and colleagues reduced the 92 items of the PQ to 16 items with acceptable sensitivity and specificity (Ising et al., 2012). The 16-item PQ can be used to screen for possible ARMS symptoms in help-seeking subjects with psychiatric symptoms (Rietdijk, Linszen and van der Gaag, 2011).

It is important to screen for psychosis or ARMS in help-seeking subjects with psychiatric symptoms because psychosis can be overlooked if subjects receive help for...