![]()

chapter one

Application of the neuropsychological evaluation in vocational planning after brain injury

Jay M. Uomoto, Ph.D.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) continues to result in disability that requires comprehensive and often lengthy rehabilitation efforts. It is costly from the standpoint of rehabilitation costs, lost earnings, and therefore, loss to the gross national product, but moreover, costly from the human suffering viewpoint. Health-care professionals are continually challenged in their efforts to return those with TBI to the workforce. The major thrust of this chapter is to educate rehabilitation professionals on the role of the neuropsychological evaluation as a tool in assisting those with TBI to return to work. The chapter is intended for the broad audience of professionals who work with individuals with TBI who may appropriately utilize the data generated through a neuropsychological evaluation.

From the moment of injury to the first day of employment after TBI, there is often a long and arduous process of treatment and therapies that prepare a person for returning to activities that approximate pre-injury experiences. There is no typical length of TBI rehabilitation. Much depends on the severity level of the TBI, the nature and extent of problems, availability of social support networks, accessible and available appropriate rehabilitation, and the circumstances surrounding re-employment and the community job market. Outcomes of rehabilitation efforts span a wide range. Fewer individuals return to work at the same level, for the same pay, and at the same number of hours per week as before the injury. Some return to a similar job at a full- to part-time level, with a reduced rate of pay. Many are totally and permanently disabled from ever working again in a competitive setting. These individuals may seek volunteer positions or pursue a vocational interests. Psychosocial outcomes encompass a similar range, from those being able to resume a familiar social and family life to those who become divorced or separated, or experience shrinking social networks.

In the context of this chapter, the task before rehabilitation professionals is to maximize the potential of the individual with brain injury to return to as high a level of pre-injury productivity as can be achieved. Further efforts in rehabilitation may focus upon establishing new and different life goals and activities. The goal of rehabilitation, therefore, involves an enormous effort on the part of both the patient and rehabilitation personnel. Hopefully, the following will provide a good working knowledge of neuropsychological assessment so that the reader will be able to utilize test findings to better the employment outcome for this population.

It is well beyond the scope of this chapter to thoroughly review the field of clinical neuropsychology. It is an ever-expanding discipline with research findings that are constantly changing the field. Interested readers are encouraged to investigate other texts, journal articles, and resources that can provide greater depth and breadth for the field as a whole. Appendix A is an annotated bibliography of some neuropsychological resources that may provide further references for more in-depth study.

Neuropsychology as the study of brain-behavior relationships

One of the earliest uses of the term neuropsychology was recorded in a lecture delivered at the Phipps Psychiatric Clinic at Johns Hopkins University in 1913 by the famous humanitarian physician, Sir William Osler.1 It was Dr. Osler’s hope that a new field be developed whose focus was to train students in neuropsychology as a means to better understand the issues of mental illness.

In a standard text by Kolb and Whishaw,2 the authors note that neuropsychology as a unified field of study has only been recognized as a distinctive area of the general field of psychology since the mid-1970s. As with many fields of study within psychology, neuropsychology has basic science, animal, and human experimental research realms, as well as a clinical application arm. There are other fields that overlap neuropsychology that are worth mentioning to provide some clarity. The emerging field of cognitive neuroscience (see Rugg3 for an overview) is a related field that deals with formulating biopsychosocial models of cognition. It is an interdisciplinary field that includes cognitive psychology, neurology, neuroscience, experimental psychology, computer science, and several other disciplines that focus on understanding human cognitive functioning. Behavioral neurology4,5 is another field closely related to neuropsychology in that its main focus is on brain function and dysfunction relative to impairments in thinking and behavior. Neuropsychiatry can be seen to overlap neuropsychology since it is concerned with psychiatric disorders that have bases in neurological substrates.

The focus of the present discussion will be those aspects of neuropsychology that deal with assessment and treatment based upon brain-behavior relationships. The term clinical in clinical neuropsychology underscores the reality that human function exists within a biopsychosocial context (see Engel6 and Paris7 for an explication of the biopsychosocial model). That is, one cannot understand human behavior unless its related biological underpinnings, psychological processes, and social or interpersonal levels of analysis are considered.

Neuropsychology is a systematic way of examining the relationship between what occurs at the biological level in the brain and what a person does behaviorally. Human behavior is extremely complex; even seemingly simple actions, such as looking at a telephone number in the yellow pages to dial for a pizza delivery, may be complex. You first scan the telephone number from left to right. This is based upon an overlearned skill (called procedural memory) that allows you to apply the “left to right” rule to this particular situation. Attention to this number takes place and numbers must be recognized as being numbers (versus letters or just random blots of ink). The set of numbers that are read must then be stored in both verbal and visual memory, while at the same time keeping in mind the type of pizza you wish to order. You then begin briefly rehearsing the sequence of numbers to be punched on a touch-tone telephone. Since a telephone call is being placed, some decision may be required to determine whether or not to use a certain prefix area code. Once the prefix is determined, you may need to decide if it’s a long distance number, in which case a “1” must be entered prior to the area code. You continue to rehearse the original seven to ten digits as you begin punching in the numbers on the keypad of your telephone, while continuing to keep in visual memory the type of pizza you wished to order.

Note, too, that the pizza order itself is multidimensional and includes the size of pizza, type of crust, and the listing of toppings. Unless you are talking on the telephone in a completely silent room without any visual distractions, there will be the additional cognitive demand of focusing one’s attention on the voice of the person on the other end of the telephone line. Your ability to filter out television stimuli or ambient room noise and focus on the rather faint voice of the person on the line (bearing in mind that you have the receiver only on one ear) may be influenced by the amount of sleep you had the night before, your degree of hunger at the moment, and other physical states. Psychological stressors, such as knowing you are trying to meet an important business deadline, may influence your ability to focus on this telephone call. Visual imagery likely engages as soon as you hear the person’s voice. Here, you are pulling up from long-term storage images of people and contexts that may be consistent with the actual situation of the person at the pizza restaurant, while at the same time constructing intelligible verbiage to convey the purposes of your call.

All of these cognitive events occur within a span of a few seconds; some occur within microseconds. The task of neuropsychology is to analyze these various aspects and sequences of cognition relative to meaningful everyday functioning. The neuropsychological evaluation attempts to capture, in snapshot fashion, the cognitive functioning status of a particular individual. This individual is evaluated within the context of specific physical and biological states. These states may be influenced by a particular set of psychosocial stressors that modify the particular cognitive capacity of that individual.

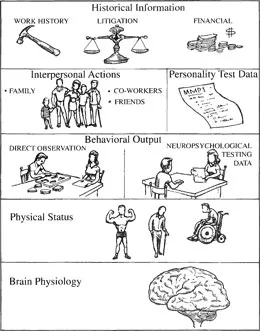

Many behaviorally oriented psychologists will maintain that there is no such thing as undetermined behavior. From a neuropsychological point of view, this also holds true. Any action that is produced by human beings corresponds to some event that occurs in the brain. While a neurologist, a physiologist, or radiologist may spend their careers examining the intricate substrates of the brain matter itself, neuropsychologists spend most of their day making observations on human behavior and drawing conclusions about what caused those behaviors. What determines a particular behavior can be viewed on several levels. Figure 1 depicts the several realms of data that a neuropsychologist will examine to assist in making sense of particular behaviors.

If a client with TBI is observed being late to work, the neuropsychologist may be asked to judge to what degree memory impairment contributes to this person’s problem with timeliness. In this case, the neuropsychologist would need to know the extent of brain injury (brain physiology) as determined by diagnostic imaging (CT or MRI scan) and/or electrodiagnostic measures (EEG). There may be physical barriers to timeliness (e.g., gait disorder, balance problems, weakness on one side of the body) which make commuting or getting ready for work in the morning a more time-consuming process. Fatigue and sleep problems after brain injury may slow a person’s morning routine, thus making him late to work. Simple observations can be made regarding lack of promptness for a neuropsychological testing appointment or if when conversing with a client, you notice that your name is quickly forgotten (direct observations). Memory tests may be given to assess both verbal and visual retention skills. Tests of attention and concentration may also be given (specific neuropsychological testing).

Inquiries into any interpersonal conflicts on the job, perhaps with a supervisor or co-worker who the client expects to see in the morning, may assist in the evaluation (interpersonal actions). It can be determined if this is an individual who is simply “laid back” vs. depressed which may make the person lethargic and sluggish at the work site (based upon personality functioning test data). Gathering information regarding the client’s litigation status may shed light on the picture. For example, does a client stand to lose compensation by “looking too functional” on the job? Are there others in a client’s social network who may have a stake in how well a person functions at home, in the community, or in a work situation (attorney, spouse, or employer)?

Figure 1 Realms of data that are pertinent in a neuropsychological evaluation.

Information about work history (historical information) can help complete the clinical picture. For example, did the person always arrive late prior to injury, or is this a new behavior? Rarely is there a single explanation for a given behavior and it is most often a combination of several of the above factors. Determining the factors that significantly contribute to a problem may assist the health care professional and, particularly the vocational counselor, in solving the problem at hand. In this case, the vocational counselor identifies the timeliness problem as being due primarily to poor organizational routines and short-term memory problems concerning the bus schedule. The counselor may then find a therapist to work with the client on use of a memory book and establish a morning organizational routine (e.g., an occupational therapist may be called for case consultation).

In sum, the study of the relationship between brain functioning and behavioral output is the primary content of neuropsychology. The neuropsychological evaluation is a method of examining this relationship. It should be noted here that there is a difference between a neuropsychological evaluation and neuropsychological testing. Testing is just one part of an evaluation.

Psychological and neuropsychological testing

Many neuropsychologists will also conduct a clinical interview with the client for diagnostic and background information. Often a collateral source, such as a family member, friend, employer, or co-worker is also interviewed. This is important since the person with brain injury may not be fully aware of the nature and range of cognitive or neurobehavioral problems that are exhibited in the home or community. Medical and other records are reviewed. A thorough examination of the medical findings and opinions can provide needed information to put into perspective how far the client has progressed from the time of injury. Emotional status and personality factors are also important variables to consider in neuropsychological assessment. To augment neuropsychological testing, an evaluation generally includes the administration of a standardized personality i...