Chapter 1

Introduction

Tim Marshall

As a city, is Barcelona particularly different from many others in Europe, especially in southern Europe? It is on the sea, and has been a port, as so many Mediterranean cities. Might we not expect a history of urban change and planning not unlike many cities in similar situations? There are after all many factors common, in very broad terms, to such a category as the “Mediterranean city” — climate, some geographical factors, certain similarities in the switchback of governmental change and war, a gradual process of modernization, particularly during the twentieth century, surges of urbanization, especially after the 1950s.

Yet Barcelona has in the past 10 to 15 years become the outstanding example of a certain way of improving cities, within both this Mediterranean world and in Europe, Latin America and even globally. The collection of articles in this book seeks to go inside this phenomenon, using the writings of those in Barcelona who have been involved in the changes or followed them very closely. The book has three objectives. First, and as the main task, it aims to give an account of what has happened in the city in relation to planning and urban change since about 1980. Familiarity with these elements should help readers to understand why Barcelona has picked itself out from the wider set of cities that might have been expected to engage in similarly creative ways — but did not. Some approach to explanation will therefore be made: not from a detached, outsider’s perspective, but from the understanding of leading actors in the process.

Second, brief sketches of current programmes for the city are given. What new approaches and challenges are emerging? May we expect Barcelona to continue to innovate in interesting ways, to deal with the emerging new issues?

Third, there is an assessment of what has happened overall in these two decades. This does not claim to be a comprehensive evaluation. Readers will make their own judgements from the main text, as well as from their encounters with the city. These final chapters are designed rather to present assessments from cultural and environmental perspectives.

The task of this introduction is to give a short overview from the outside, to help readers to situate the accounts which follow. This overview will have five parts. First, I will outline the geographical and historical realities which lie behind and underneath the recent events. Second, I will comment on the traditions of urban planning in the city and, more widely, in Spain. Third, a set of “schematic facts” on the changes will be presented. The emphases I give to these “facts” are, of course, quite personal. Fourth, I will develop these summaries under some key dimensions of change, which may serve as headings for collecting together assessments from later chapters and from further analysis in the future. Finally, I will comment briefly on achievements and prospects, to give a personal take on the city’s contemporary history.

Many of these issues can be followed up in the literature on the city, which is gradually growing. I have brought together what I hope is a reasonable selection of that literature in the Bibliography at the end of the book. This is made up only of publications in English, and so makes no claim at all to international general coverage, and certainly does not touch the more extensive writing in Catalan and Spanish.

Barcelona’s history and geography

The most important features of the city’s geography stand out on Figure 1.1. Climate helps. Unlike many European cities, Barcelona has neither very intense heat (just unpleasant humid heat in July and August, normally), nor cold — rarely sub-zero temperatures, just slightly cooler and wetter winters. Few other medium or larger cities, whether in Spain or elsewhere in Europe, have these qualities — except, perhaps, Valencia.

1.1 Physical location of Barcelona, shown on plan of 1934

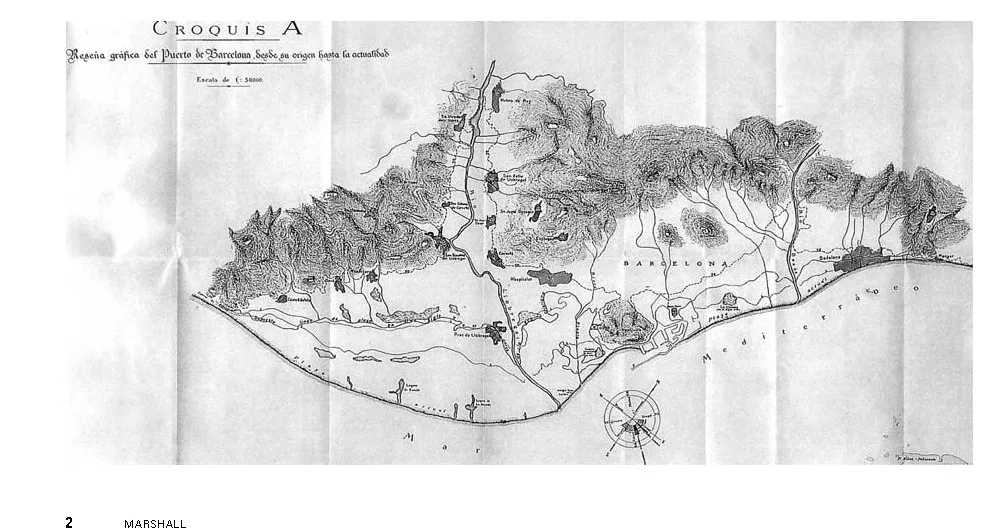

1.2 Coastal zone of Barcelona, 1923

The coastal location gives certain advantages — moderating the climate, easing communication for many goods, giving many leisure opportunities, serving as a sink for myriad wastes throughout the city’s history. The position at a much wider scale has been emphasized as strongly conditioning in history (Vilar 1964). Barcelona is situated on a coastal corridor between France, Italy and the north, and the south and Africa. There is a thin strip along the coast itself from the city northwards, a range of hills behind that, and a wider inland depression, along which the Romans placed the Via Augusta. This location, in a kind of “march” or border country between zones of activity and civilization north and south, is seen as a vital factor in the forming of Catalonia, and with it Barcelona, as always the unchallenged capital (see Figure 1.2). Catalonia is seen as always taking much from the Europe to the north-east, and feeding these influences southwards. Its location has been one factor maintaining its cultural and political separateness, evidenced frequently over the period since the 1000s or 1100s when Catalonia may be said to emerge into a national history.

The nearest competing urban centres are far away, reflecting Spain’s challenging geographical nature — Valencia 373 km south, Zaragoza 296 km inland, Madrid almost out of sight at 621 km. Southern France and Italy have often been as near as or nearer than most of Spain, in practical terms (both Marseilles and Bordeaux are slightly nearer than Madrid).

At a more local scale, the specific features of Barcelona’s situation are that it is on a rather wide sloping site between the mouths of two important rivers, the Llobregat to the south and Besòs to the north. These rivers formed deltas, an important fact in the later Middle Ages when the deltas were brought under control and exploited for successive purposes (hunting, agriculture, water supply, waste dumps, industrial and airport sites, etc. — Marshall 1994). The rivers served as trade routes, channelling commerce into Barcelona. In the twentieth century, the rivers and deltas have been increasingly central in setting the opportunities and constraints open to planners or to urbanizing developers.

The other side of those constraints has been the balance of hills and flatter areas available, with the relatively inaccessible parts of Montjuic and Collserola setting limits to development, and then progressively becoming available as important leisure and ecological zones.

The importance of geographical and environmental history has been matched by that of economic and political history. Economically Catalonia, and Barcelona at its core, has been one of the two powerhouses of Spain in the past two centuries (with the Basque country). The accumulation of capital both within the territory and remotely via the Spanish empire (especially in Cuba up to 1898) allowed the continuing relative prosperity of the city and a continuing pressure to extend the urban area from the eighteenth century onwards. The bourgeoisie acquired sufficient wealth to drive the urbanization from that time on, and to import and develop a thriving material and artistic culture. Reserves of labour, first from the Catalan countryside and then from further afield in mid- and south Spain meant that lack of labour power did not constrain industrialization. The availability of cheap hydroelectric power from 1908 on, from the Pyrenees schemes, also favoured twentieth-century industry. A further essential boost was the formation of a chemical and oil complex from the 1950s in Tarragona, near enough but not so near as to blight the city’s image. Nuclear power stations in the same zone of southern Catalonia followed in the 1970s. North African oil and gas were also easily importable. Barcelona’s ecological foundations are varied.

This process of economic change through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was not, of course, without its tensions, socially and politically. Class and interest struggle, at the workplace and in the city, was a more or less continuous feature of economic and political life, forming a central contribution to wider developments in Spanish politics. The epic all Spain conflict of the Civil War 1936–39 overshadowed earlier and more localized struggles on the city streets, and fFurther bouts of central control in the Primo de Rivera regime of the 1920s and the prefigured the largely more pacific era of anti-dictatorship movements of the 1960s and early 1970s. The civil war defeat of Catalonia, and with it Barcelona, is a vital ingredient in the urban history of the period since then. This is one of the distinguishing features that must be at the forefront of any explanation of planning’s vitality since the 1970s. The political nature of that force may be distasteful to some who expect design and regeneration to emerge seamlessly from vibrant and inspired creative professionals. Barcelona’s experience has not been the sanitized story it is sometimes presented as. Donald McNeill’s book (1999) on the city has given English-language readers much of the basis for a more sensitized understanding.

Another vital feature was the success of industrial development in the region, giving a base of confidence for tackling the challenges of urban stress; challenges that came with the period of rapid urbanization from the 1950s to the 1970s. Car ownership, motorways, second home ownership, higher living quality expectations, high rates of immigration, a larger local tax base, great expansion of higher education: all these laid foundations for the response made after 1980. Francoism’s “great leap forward” after 1959, opening the economy to foreign investment, was essential to the catch up to near western European living standards. If the new city council in 1979 had started from a 1959 economic base, the options would have been utterly different, for good or ill (Salmon 1995, 2001).

The spread of development can be seen on Figure 1.3. The core municipality of Barcelona had successively annexed surrounding municipalities between the 1870s and the 1920s, so that it had space to control its own growth up to the most recent decades. It is true that in the second half of the twentieth century there was also massive growth in the “first ring” of municipalities, which virtually joined with Barcelona by the 1970s, forming a “real city” of over 3 million inhabitants. But the challenge of dealing with this wider scale was one to be addressed largely later.

This political issue of jurisdictions was very important, as students of large cities around the world are aware (Sharpe 1995). Barcelona became, through annexation, large enough to make its weight count, matching resources to the confidence which came with knowing that, quite clearly, it was Catalonia’s capital and the challenger to Madrid in directing Spain’s trajectory. This issue of political power runs through the planning history of the city for centuries, and gives a backdrop to every single big planning decision. The dynamics work at two main levels. The most important has always been between local forces in the city itself, and the Spanish state marshalled from Madrid. The subjugation of the city in 1714 meant over a century of being controlled by two overlooking fortresses and a ban on building outside the city walls. The release of that ban in the 1850s and the demolition of one fortress (the Ciutadella) allowed the “Extension” of the city (Eixample in Catalan, Ensanche in Spanish). Further bouts of central control in the Primo de Rivera regime of the 1920s and the Franco era 1939–75 left many further marks on the city’s growth. The final period of relative freedom has been a time of autonomy, delightful for its freshness. But even that period has been full of a continuous negotiating with funding and regulating ministries in Madrid, mediated by party allegiances and nationalist differences — for example in the central government’s funding of the Olympics schemes and the 2004 projects.

1.3 Urbanisation of Barcelona 1900, 1925, 1950, 1980

The secondary scale dynamic has been that between the city and the wider region, particularly the nation of Catalonia. Before 1980 this interplay was marked by the absence of any significant body at that level, except for the Metropolitan Corporation formed in 1974, made up of Barcelona and 26 neighbouring municipalities. This absence left the main tension as that between city and central government, with no one to represent the wider area, whether a metropolitan zone or the nationally defined territory of Catalonia or the even wider “Catalan lands” (with Valencia and the Balearic Islands). Since 1980 there has indeed been a powerful representative of Catalonia, the Generalitat, one of the 17 autonomous regional governments given major powers under the semi-federal constitution of democratic Spain. This body, run from 1980 to 2003 by the centre-right Catalan nationalist party Convergència i Uniò, led by Jordi Pujol, abolished the Metropolitan Corporation in 1987 and sought to exercise strong influence over planning throughout Catalonia. It succeeded in this to a greater extent outside the metropolitan area than inside it. In Barcelona, and nearby, its influence has been rather one of impeding major efforts to plan long term and coordinate, than giving positive leadership. However, the Generalitat has broadly cooperated with Barcelona City Council in concrete projects such as the Olympics and the 2004 Forum.

The nature of Barcelona’s planning tradition

As readers of the book will detect (especially in the chapter by Esteban), there are several contenders as to who were the key agents and what were the essential techniques involved in Barcelona’s transformation. But most are agreed that one ingredient has been an ability to plan. In Spain, there has long been a system of forward planning of towns and cities, called “urbanismo” (urbanisme in Catalan). This is particularly well entrenched in Catalonia, especially because of the legacy of one of the great founders of planning, Ildefons Cerdà (Magrinyà and Tarragó 1996, Soria y Puig 1995, Ward 2002). Cerdà is a strong candidate for the title of the first modern urban planner. An engineer by training, he also studied the society he was addressing with major statistical surveys. Politically, he was a utopian socialist, though one ready to get his hands dirty in the business of planning and trying to implement the expansion of Barcelona. His plan of 1857 for the city remained the legal plan until 1953 (colour plate 1). The plan was often criticized in the succeeding century, but formed the foundation for a series of subsequent exercises, the most important being those of Leon Jaussely (1903), the modernists in GATCPAC (1931–33) and the Franco era plans of 1953 and 1968, which tackled the wider metropolitan region as much as the city itself (Figure 1.4 shows these plans).

1.4 Plans for Barcelona: (a) Cerdà 1860 (b) Jaussely 1905 (c) Rubió i Tuduri 1932 (d) Macià (Le Corbusier/GATCPAC) 1934 (e) Pla Comarcal 1953 (f) General Metropolitan Plan 1976

This tradition of making plans, and to varying extents implementing them, gave legitimacy to planning activity in the city. Often the city was ahead of developments in Spain generally; the first coherent national planning law was passed in 1956. Planning was carried out by the physical design professions, engineers and architects — especially in recent years overwhelmingly by architects, many with supplementary training in planning (urbanisme) within their architecture degrees. These architects cooperate closely with other key professionals, above all economists, who have to check that the complex funding arrangements for infrastructure will succeed. The writings of many pla...