Introduction

The 330 most used terms in architectural debate

Widely used in architectural circles in the heat of discussion, the recurrent use of particular terms has evolved into a language of building design. Commonly found in architectural literature and journalism, in critical design debate, and especially in student project reviews, Archispeak can seem insular and perplexing to others and, particularly to the first-year architectural student, often incomprehensible.

Architects enjoy engaging and articulating these terms. Indeed, when in full flow, they are prone to modify and adapt the meanings of existing words or, when stuck for a term, will often spontaneously invent a new one. However, drawing from a diversity of sources, the emergence of this subculture also reflects the need to translate architectural design concepts into spoken commentary—each term embodying a precise and generally accepted architectural meaning. Inadvertently, this unique form of expression can also disclose a critical wish list’ that emanates from a consensus of issues and strategies considered crucial to an idealized design approach. Therefore, if we explore the vocabulary of this language we gain insight to a collective understanding of what constitutes ‘good architecture’. Hopefully, if the first-year student can understand the nuances of the language, he or she will be better able to address and communicate these issues and strategies, and, thereby, improve the quality of their design commentaries. This is the core purpose of this book.

To make Archispeak easily understandable and accessible to the reader, each term is defined in the context of its architectural usage; white many definitions are illustrated, all are cross-referenced. Also, some of the definitions are written by architects and educators whose work and criticism draws from a use of particular terms. Finally, Archispeak is intended as a primer, each definition being offered as an appetizer, which, hopefully, will provide a springboard to further reading and a deeper understanding.

Allegory An allegory is a story where figures, in the form of humans, animals or superhumans (gods and fantasy figures) are used to illustrate abstract concepts, qualities or situations. Showing one thing and meaning another, allegory is a mode of representation, usually naturalistic, that uses the veneer of one narrative to disguise the deeper meaning of another. Usually referring to some outstanding quality or exceptional situation, allegorical meaning remains hidden. Therefore, like an illusion, allegory is elusive; it is a palimpsest that awaits its inner message to be disclosed and decoded. In Signs and Symbols (1989), Adrian Frutiger writes that the majority of allegorical figures in Western culture are derived from the mythology of ancient Greece and imperial Rome. However, their investment with attributes were later assigned, possibly in the Middle Ages and especially during the Renaissance, when Truth’ was a principal tenet of humanism. An allegorical layer of meaning was inscribed by Andrea Pisano's sculpture on the lower sections of Giotto's campanile, built in fourteenth-century Florence. Carrying ‘comic-strip’ bands of sculpture, each façade represents a ‘page’ of cryptic ‘text’ that codifies the virtues, the sacraments, the arts, the planets and so forth.

An allegory can convey a message with moral overtones; allegory personifies the values of a culture that create it. The combination of the historical figure with symbolic object produces an abstract statement with a message that is allegorical For example, the winged female form shown here is the generally understood representation of victory and peace, the blindfolded female figure holding a sword in one hand and a pair of scales in the other represents justice, and the Statue of Liberty, carrying a torch for freedom to light the way, extends the hand of friendship to the displaced. These robed women are not merely symbols that connect the visible and an invisible world, but are an allegorical picture of a real phenomenon.

Frutiger suggests that in the wake of the fading allegorical images of the past, new forms are emerging. For instance, all the robed variants of Superman and Superwoman, together with the science fiction heroes of outer space, will probably provide the replacement models of a future allegorical expression.

See also: Anchoring • Didactic • Narrative • Palimpsest • Semiology • Sign

Ambiguity

Ambiguity is a double entendre, an enigmatic or equivocal characteristic that appears in art, literature and architecture. Like its bedfellows, paradox and contradiction, it is a consequence of a balance of opposing forces at work. Ambiguity plays upon our educated vision and induces in the viewer the confusion of a bifocal vision—a mixed register that results from either deliberately cryptic intention or the dubiousness of inexact expression.

Ambiguity is the condition of not being able to believe your eyes in which what you get is not necessarily what you bargain for. It is experienced in the optical conundrums posed by Maurice C.Escher's graphical illusions and in the light sculptures of James Turrell, where the interface between matter and space becomes diffused. Architectural ambiguity is famously exploited in Jacques Tati's movie Playtime, in which he uses the anonymity of International style sets to blur differences between interior and exterior and between one building use and another. In order to further confuse both the screen character and the audience as to what is real and what is illusion, Tati exploits to the full the ambiguous duality of transparency and reflectiveness in glass—the symbolic material of Modernism.

The winged figure of Nike erectedin 185 BCE in Samothrace allegorically signifies victory in battle.

The ancient Greeks were anxious to avoid ambiguity in the formal appearance of their temples. In order to do so, they employed ‘entasis’, i.e. a subtle inflection of the contour of mass as a means of correcting the apparent distortion caused by excessive straight edges. By contrast, ambiguity was heavily promoted by many post-modern architects and critics who argued for a layered complexity of allusion, metaphor and contradiction as a means of enriching the experience of architectural form and of placing the onus of its interpretation upon the spectator. Obviously, one antidote to ambiguity is to use an unequivocal primacy and a clear hierarchy in the ordering of events.

See also: Analogue • Complexity • Disjunction • Metaphor • Paradox • Sign

Analogue

Analogies are forms of inference: from the assertion of similarities between two things is then reasoned their likely similarity in other respects.—Albert C.Smith

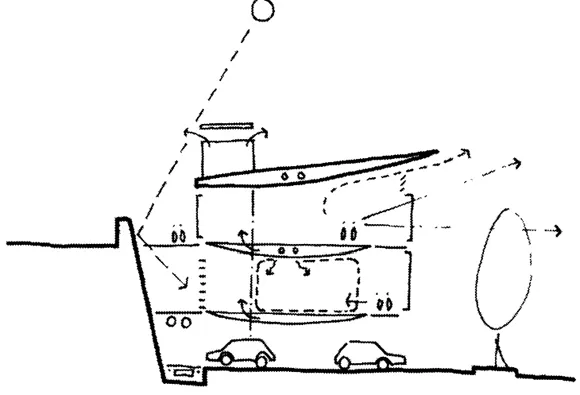

There are basically two forms of architectural analogue. The first is the architectural drawing or model, which is an analogue of the building it represents. The architectural drawing was invented over 5,000 years ago so that ideas could be tried out before the building is built. Drawing grids and tools, such as the T-square, predetermined that Euclidean geometry would be the Language of architectural form. In a similar way, computer software is now influencing potential building forms. One could not imagine designing Frank Gehry's Museum in Bilbao with a T-square. Analogue takes over—that is, predetermining the range of possible building forms; but the means by which the drawing or model is executed may be more powerful than we realize.

The second type of analogue is the building that looks Like something else that is not a building at all The most famous of these is the Dinosaur building featured in the cult movie PeeWee's Big Adventure. Charles Jenck's in The Language of Post Modern Architecture (1977) featured buildings as hot dogs, running shoes, as well as human genitalia. Other well-known analogue buildings are Cinderella's Castle at Disneyland and most of the newer casinos in Las Vegas, especially New York, New York, which is a building that is analogous to an entire city.

All reductive drawings and diagrams that selectively process, filter or distil information are analytical in intent.

Analogies are forms of inference: from the assertion of similarities between two things is then reasoned their likely similarity in other respects. (EO)

See also: Allegory • Metaphor • Sign • Semiology • Symbolism

Analytical drawing

The purpose of the analytical drawing is to visualize the spatial characteristics of a building. In order to do so, analysis is a process of reduction— essentially omitting all relevant data from a design drawing so that only information essential to the study remains. The art of making such a drawing is deciding what use is to be drawn and what left out. Such drawings should make sense at a glance and should be self-explanatory rather than requiring explanation. Often, a series of drawings with a limited quantity of data is much easier to read than a single drawing containing a great deal of information.

See also: Diagram • Diagramming • Morphology

Anchoring

The excessive weight attached to the question of where one is, goes back to nomadic tribes, when people had to be observant about feeding-grounds.—Robert Musil

Anchoring is a term using to describe the physical and metaphysical rooting of a building to the context of its setting. Literal anchoring devices include the sculptural or architectural plinth, which, like the base of a column or the emphasized ground line in an elevation or section drawing, establish the form as ‘growing’ from the earth while simultaneously mediating between ground and edifice. The link between the building and the earth upon which it stands is sometimes expressed with a lower band of coarse stonework, such as in the rusticated first-floor levels of Renaissance palaces. Also, while external staircases ‘stitch’ together ground and building, columns will appear to spring from the earth to hold up (and hold down) a sheltering plane that appears to belong to the sky. Historically, stone-based and clay-based settlements were built from the substrate on which they stood, masonry or brickwork precisely reflecting the geological nature of their setting. Even a lick of local colour can function as a rooting device. For example, rather than be gilded to symbolically commemorate the 184–9 gold rush, as originally planned, San Francisco's Golden Gate bridge was painted in its existing oxide red to visually anchor its structure to the colour of bedrock on each side of the bay.

However, Steven Holl proposes that a metaphysical or poetic anchoring is more appropriate for modern life. For instance, when a new architecture is fixed into a place in space and time, a more profound connection can be evoked through memory and through the architectural inscription of historical traces on a site. This is a strategy in which materials can speak of disconnected points in time—like the frosted glass planes on Holl's competition project for Minnesota's State Capitol archive, which echo the primordial glaciers that formed the local terrain in the Pleistocene period. There is also his incorporation into the same design of an abstract footprint of the original buildings, which forms a fossilized impression of Minnesota's first State Capitol These are not literal reconstructions but, as Holl points out, are ‘compressed allegorical accounts of the history of Minnesota’.

The concept of anchoring finds an echo in Peter Eisenman's notion of ‘trace’—a type of critical regionalism taken to a poetic level It also has roots in Martin Heidegger's and Christian Norberg-Schultz's phenomeno-logical ideas about site, together with Gottfried Semper's ‘stereotonics’—an aspect of buildings that sees hearth and masonry as locked into a site and grounded in the earth.

See also: Allegory • Focal point • Memory • Place • Trace

Animate

Animate means to give life or make lively. When heard in architectural debate, the term usually refers to the need to breathe life into a drawing or a design. In other words, it is usually employed as a critical kick-start to schemes or their representation that appear dull or lifeless.

Animated drawings are those apparently created with the spontaneity of the quick sketch, i.e. drawings whose lines that, resulting from the immediacy of directness of thought and purpose, appear to trace the essential dynamic of an idea. Many tutors will preach the exploitation of Line weight as an antidote to bland and inanimate-looking drawings; others will recommend that Life is breathed into more rigid and wooden-looking hard-line drawings by tracing over them in freehand.

Architectural design schemes appear animated when their form and space appears to imply movement— not actual movement but an implied dynamic. Animation is the technique of filming successive drawings or positions of models to create an illusion of movement wh...