1

Introduction

Hail, son of Kronos,

Welcome, greatest Kouros,

Mighty of brightness,

Here now present, leading your spirits,

Come for the year to Dikte

And rejoice in this ode,

Which we strike on the strings, as we

Blend it with the sound of pipes, as we

Chant our song, standing round

This your well-walled altar.

(Hymn of the Kouretes to Diktaian Zeus. From Palaikastro,

c. 250 AD, but representing a much earlier tradition)

In the short time that has elapsed since Sir Arthur Evans effectively rediscovered the Minoans in the early 1900s, the people of bronze age Crete have become familiar figures in our mental landscape of European prehistory. We have come to accept as established and defined a whole string of cultural traits that go to make up the ‘Minoan personality’. The Minoans were elegant, graceful people who took an innocent pleasure in displaying their own physical beauty; they were lithe, athletic and enjoyed boxing, wrestling, and bull-leaping; they were intensely refined aesthetes, surrounding themselves with sophisticated architecture and beautiful objects; they were nature-lovers, commissioning frescoes of landscapes full of flowers, birds, and butterflies; they were collectively strong, too, with fleets controlling the seas surrounding Crete, so minimizing the danger of attack by would-be invaders; they were lovers of peace, the inhabitants of each city-state living in harmony with their neighbours; they were ruled by a great and powerful king of Knossos called Minos.

But how far does the work of subsequent archaeologists in Crete support this widely held view of the Minoans? It is appropriate, as we approach the centenary of Evans’ historic 1900 excavation, to take stock of the evidence. It may well be that we need to revise our image of the Minoans in the light of that evidence.

Until about a hundred years ago, it was customary to see the history of the Aegean world as beginning with the First Olympiad of 776 BC. Although it was recognized that the region was inhabited before that date, all the events of that earlier period were regarded as lost beyond retrieval and any references to them treated as pure legend. The heroes and heroines of Greek folklore and myth were tossed aside by scholars: they were as unhistorical as the gods and goddesses.

In the wake of Schliemann’s and Evans’ discoveries at Troy, Mycenae, Tiryns and Knossos, there was a tendency for historians to swing to the opposite extreme. The historical reality of Troy seemed to prove the existence of Priam, that of Mycenae Agamemnon, that of Knossos Minos. Bury (1951), for instance, accepted such figures as Perseus, Minos, Jason, Theseus, and even Heracles as historically real people, pointing out in support of this position that the Greeks themselves believed in their reality and that (in Homer, for example) they were given fairly consistent biographies and pedigrees. But this extreme position is fraught with difficulties. The Greeks not only believed in Theseus and Jason: they believed in Prometheus too – Prometheus, the creator of mankind – and put the time of his existence at around 1600 BC. Since we know that the Minoans built the second temple at Knossos some one hundred years before this date and we also know that the Minoan civilization had been developing for a thousand years, there is no possibility that the Greek idea of Prometheus could have been historically correct.

Modern historians and prehistorians take the more moderate view that these emblematic figures were folk-heroes, symbolically representing remote but powerfully significant events all but lost to the Aegean folk-memory. Impressive events in the communal past, such as changes of dynasty, the arrival of waves of foreign settlers, wars, invasions, migrations, were summarized in the epic life events of the folk-heroes. Some may turn out to have been real people, and finding their homes by means of archaeological excavation may persuade us that we have discovered the people themselves, but they may well not have been the figures presented to us by the Greeks. Discovering the Knossos Labyrinth implied to Sir Arthur Evans and many who followed his line of thinking that King Minos too had been traced, though this is not the case. Even if a kingly burial had been discovered by archaeologists at Knossos, which significantly it has not, we could still not be sure that the corpse was that of the majestic and tyrannical ruler of the Minoan sea-empire presented to us in Greek legend. Eratosthenes’ dating puts the Trojan War at 1183 BC and King Minos into the third generation before that. Minos’ floruit was thus, in the Greek view, around 1260 BC – about a hundred years after the date generally agreed by archaeologists for the abandonment of his alleged palace at Knossos. As Thomson (1949) says, it may be better to accept the general substance of the Greek stories, or at any rate to bear them in mind, and let the dates go; certainly the Greeks foreshortened the time-scale for the early events in Aegean prehistory.

Archaeology has added a new dimension to our view of the Aegean. Instead of beginning with the First Olympiad, we now have a much longer perspective revealing a complex cultural evolution stretching back two thousand years further. We have a picture of a prehistoric preamble which is finely detailed and becomes increasingly so with each new archaeological dig. The most startling result of Aegean archaeology during the last hundred years has been the discovery of a complete, original, and previously unsuspected civilization which existed before the Homeric age. The Minoan civilization had all kinds of repercussions on the development of the Greek culture which developed later, yet, extraordinarily, the historians of the fifth century BC, Herodotus and Thucydides, had comparatively little to say about the culture or history of Crete. Why was it that the glittering originality of Minoan Crete vanished from the Greek consciousness within a few centuries of its demise? Was it that the Greeks were too proud of their own civilization to acknowledge the existence of an earlier civilization, one that rivalled or surpassed their own? Or was it that the Minoan civilization had been so totally destroyed that they were unaware of its character?

Certainly the Greeks inherited some strange tales and a large amount of cult activity from the Minoans, but they seem to have been unconscious of their true origins. It may be, as Thomson suggests, that the post-Minoan invasion of Crete and Greece by Dorians from the north cut Crete off from mainland Greece and that when the eastern Mediterranean recovered from this trauma the Greeks resumed trade with Egypt and the Levant direct, without landing on Crete. Whatever the explanation, there is a strange discontinuity at the end of the Minoan civilization; it was as if a door closed on it, only to be opened again after three thousand years.

Minoan Crete may be seen as a cradle of civilization on a level with the Nile, Indus, Tigris, and Euphrates valleys. Arguments are sometimes advanced that the Minoans borrowed much of their culture from Egypt, Syria, or Anatolia, but theirs was a very distinctive culture, however it was assembled or generated, and certainly distinctive enough for us to treat it as an original creation. It could be argued that the Minoan art of fresco painting was borrowed from Egypt, and it may be so, but the artistic effects and even the subject matter are very different; it is clear that the Minoans developed the art in a way that was strongly characteristic of their own personality, making it an integral part of their own culture. So it was with many other cultural elements, and to such an extent that we get, even from fragments of artefacts, a strong sense of the Minoans’ personality. After reviewing all the many elements of the culture in the opening chapters, we will come to a discussion of this Minoan personality, utilizing the latest archaeological evidence from Crete in order to achieve the clearest picture. It is possible to gain access to the everyday life of the Minoans and also, to a surprising extent, to their emotional and spiritual world too.

The Cretan bronze age was an extended period of cultural growth, beginning in about 3000 BC and ending in about 1000 BC. During this long period there were many changes and we need to be aware that when we identify particular traits as ‘Minoan’ we are often thinking of the culture as it was at its peak, in the three centuries preceding the abandonment of the Knossos Labyrinth in 1380 BC. But this pinnacle was reached after a millennium of evolution. From the outset there was an ambitious pattern of trade by land and sea, and complex bartering negotiations with numerous foreign neighbours as far afield as Egypt. Civilization in Egypt was at that stage in advance of the Cretan culture and it may well be that contacts with a more advanced culture stimulated the Cretans. Contacts with Anatolia gave the Cretans access to crafts, artefacts, materials and ideas that had come from Mesopotamia, and these too had their effect in stimulating development; the idea of using sealstones, for instance, seems to have been developed from a few samples imported from the east.

Gradually, during the Early Minoan period (3000–2200 BC), the Cretans evolved all the characteristics that we think of as being distinctively Minoan. Only the ‘palaces’ remained unbuilt. The ‘palace’ society (c. 2000–1380 BC) was clearly very advanced in its orderly and bureaucratic organization, showing a strongly rational and practical side with highly developed craft technologies, and yet it also possessed all the imaginative power and childlike freshness of a very young culture. This combination of skill, power, and freshness is exemplified in the frescoes and crafted cult objects, many of which seem to spring from a pervasive religious feeling. Towards the end of the Late Minoan Period (the end of the second millennium BC), religion seems to have dwindled to a rigid and sterile formula for appeasing the deities of what must have seemed an increasingly hostile cosmos. Nevertheless, at the zenith, during the heyday of the so-called ‘palaces’, the religious life of the Minoans was rich and vibrant. There were moments, quite frequent to judge from the artwork, when gods and men and, more importantly, goddesses and priestesses, were brought together in astonishing unions. In epiphanies of startling drama, men, women, birds, and even pillars and boulders were transformed into deities; gods and goddesses appeared and walked among worshipping mortals, exalted but humanized and accessible.

This religious zeal, amounting to intoxication and possibly actually enhanced by alcohol and opium, is expressed in a wide range of art objects; the frescoes decorating shrines and sanctuaries, the cult vessels, the religious scenes on the sealstones are all executed to the very highest technical and artistic standards. Again and again when we look at objects such as the Mallia bee-pendant or the Boston Goddess, we sense that the Minoan craftsmen were over-achieving, extending their crafts almost beyond the technical limits of the age. In the virtuosic handling of clay, bronze, and many kinds of stone, they surpassed themselves and we may sometimes feel that the spirit of the age was adventurously romantic rather than pre-classical. The proud figures of the men in the frescoes may look to us like overreachers, vain and perhaps vainglorious; perhaps the idea of hubris, vanity in the face of the gods, had not yet evolved and this was still an age of innocent self-pride.

The images of men and women, warriors, worshippers and priestesses give us evidence of their appearance and also of the way they saw themselves, which is every bit as important. Assembling a picture of the Minoans is complicated a little by uncertainty about the authenticity of some of the art objects, especially those not found in modern excavations. No one knows for certain where the beautiful ivory statuette known as the Boston Goddess came from; it seems likely that it was robbed from a surface layer in the ruins of the East Wing of the Knossos Labyrinth, and in terms of materials, shape, and the techniques used in making it, it is characteristically Minoan, and therefore probably genuine. The Ring of Minos, given its known findspot at the site where the Temple Tomb was later unearthed, and given its style and content, is also taken here to be an authentic Minoan ring (see Chapter 6 and Figure 39). Nilsson’s objection (1949) that the picture on it is derivative and that it could have been composed from a knowledge of three or four other cult scenes is unconvincing. Significantly, the scene on the Ring of Minos is consistent with what we are learning of Minoan cult activities, and is therefore likely to be genuine.

The Ring of Nestor is another matter. Although many of the elements in its composition appear to be Minoan, they have been assembled in a peculiar way, as four scenes quartered by a ‘Tree of Life’. It shows, according to the Evans interpretation, a couple being initiated into the mysteries of the otherworld, where the Tree of Life has its roots: the two people appear before a goddess and an enthroned griffin. The initiation is followed by resurrection and the couple’s return to the world of the living. In this case, Nilsson’s reasons for doubting the ring’s authenticity are well founded. Nowhere else, for instance, is a griffin shown enthroned. Often a griffin or a pair of griffins are attendant on a standing or seated goddess, but it is inexplicable for the roles to be reversed. Another scene shows a lion enthroned on a sacrificial table; this too is incongruous, and suggests that the craftsman who made the ring did not know what the table was for. Although the vocabulary is Minoan, the syntax is not. The Ring of Nestor is therefore treated as a fake and consequently not referred to in later chapters as evidence of the Minoan belief-system.

The Minoans and their civilization have been written about before, but there is a pressing reason for reviewing them now. In The Knossos Labyrinth (Castleden 1989), the nature and purpose of the so-called ‘Palace of Minos’ at Knossos were called into question and an array of arguments was presented for treating the building as a bronze age temple-complex. It was shown, for example, that the distribution of findspots of religious cult equipment round the building indicates that a very large area of it must have been given over to cult activity.

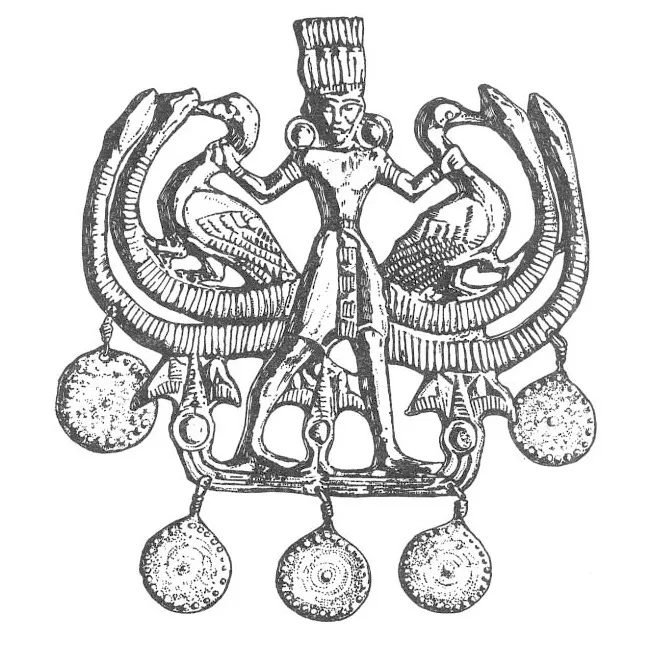

Figure 1 The Aigina Treasure Pendant. Found on Aegina, near Athens, but almost certainly a Minoan masterpiece made in Crete between 1700 and 1600 BC

When comparisons are made between Minoan Crete and pharaonic Egypt or Hittite Anatolia or the cultures of Mesopotamia, interpreting the ‘palace’ at Knossos as a temple – and, by implication, the other Cretan ‘palaces’ as temples too – seems quite natural. The Hittite capital, Hattusa, possessed several temples, the largest of which was in many ways similar to the contemporary Knossos Labyrinth. As Professor Alexiou has pointed out, there was a broad similarity between the social and economic conditions prevailing in Minoan Crete and those in the Mesopotamian and Anatolian cultures. It follows that if the Hittite and Sumerian temples were large buildings, focal to the societies and economies of their cities and territories, Minoan society might have developed in a similar way. The problem seems to lie in the existence of extensive store-rooms in the Minoan palacetemples, implying a major redistribution role in the economy, but this need not preclude a fundamentally religious role for the building. In ancient Egypt it was normally the kings who dominated trade, but temple-priests were nevertheless also engaged in trade. It seems to have been particularly during periods of weak royal control that the temples engaged in large-scale trade. A priest of Ammon, for example, travelled to Byblos with gold and silver to buy timber to build a sacred ship; after some haggling, the Prince of Byblos delivered timber in return for gold, silver and raiment. There seems little room for doubt that the Knossos Labyrinth played a central role in the economic life of the surrounding central Cretan territory, and that its priests and priestesses were involved in foreign trade, the organization of public works and the allocation of rations to workers, as well as playing a central role in ceremonial and religious life – just like the temples of the east.

Trade went on at a surprisingly ambitious scale, exclusively by barter. Fourteenth-century BC correspondence regarding barter has been found at Amarna in Egypt; Pharaoh sent ‘presents’ of gold to the king of Babylon and received gifts of horses and lapis lazuli in return. The king of Alasia ( = Cyprus) offered 500 bronze talents in exchange for silver, clothing, beds and war chariots. There are even records of trade with the Minoans themselves, ‘gifts from the Princes (or leaders) of the Land of Keftiu and of the isles which are in the midst of the sea’. These were probably direct exports to Egypt of manufactured goods from the Cretan temples. In return the Egyptians sent gifts of gold, ivory, cloth, stone vessels containing perfume, chariots (probably in kits) and probably monkeys and Nubian slaves.

The economic aspects of the Minoan culture have become fairly clearly established, but interpreting the largest buildings in the Minoan towns as temples rather than palaces shifts the culture...