eBook - ePub

Lighting by Design

Christopher Cuttle

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 264 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Lighting by Design

Christopher Cuttle

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Lighting by Design provides guidance on where to find inspiration for lighting ideas, how to plan the technical detail and how to execute the plan to create safe, effective and beautiful schemes. Christopher Cuttle's unique three level approach uses Observation, Visualisation and Realisation as the means to achieve these aims. Cuttle is a well known figure in the UK, US and Australia and New Zealand, with a wealth of experience of both teaching and practice. This new edition is fully updated and produced in full colour with many new diagrams and photographs. It will be immensely useful to professional and student architects, interior designers and specialist lighting designers.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Lighting by Design un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Lighting by Design de Christopher Cuttle en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Architecture y Architecture générale. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part One: Observation

All discovery starts with observation. Whether we think of Aristotle leaping out of his bath and startling the Athenian townsfolk with his cries of 'Eureka!', or Newton wondering what caused the apple to fall on his head, or Einstein imagining himself to be sitting on a photon, or Sherlock Holmes' admonishions to Watson: it is all a matter of observation.

The process of visual perception operates throughout our waking hours, continually seeking to make sense of the flow of information being delivered to the brain through the sense of vision. It is obvious that lighting is necessary for vision to operate, and there is a substantial amount of knowledge on ways in which lighting may influence how well the visual process is able to operate. However, this book is more concerned with how lighting may influence our perceptions of our surroundings. There is far less reliable knowledge, and it takes careful observation to identify the aspects of appearance that we rely on to form our perceptions, and how they may be affected by lighting.

While this may seem to be a daunting task, it should be obvious that the essential components of lighting design are there for all to see. The first vital step towards becoming a lighting designer is to develop confidence in the evidence of your own eyes.

Visible characteristics of objects | 1 |

At first, it seems obvious that we provide lighting to enable people to see, so that all lighting can be assessed in terms of how well it enables people to see. Lighting that maximizes the luminance contrast of visual detail enables very small detail to be accurately detected, and this is the basis of many lighting recommendations and standards. However, observation of our surroundings shows a much larger range of ways in which objects can differ in appearance. Consider for a moment the judgements that we commonly make in deciding whether a surface is clean and dry; whether fresh fruit is good to eat; or whether a colleague looks tired. These judgements are based on observation of appearance, but what are the differences of appearance that are critical in making these judgements? Any of these everyday assessments of appearance can be influenced by subtle aspects of lighting, and so too can our more complex assessments of the appearance of architectural spaces.

A basis of theory enables designers to examine their own observations of the things that surround them. Differences of object appearance have their origin in the physical processes by which light is reflected, refracted, dispersed and scattered by matter. But human vision did not evolve to enable us to observe these processes: it evolved to enable us to recognize our surroundings. Understanding of the roles of these processes requires directed observation, and when we apply observation analytically, we find that the number of physical processes that is responsible for all of the differences that we can discriminate is quite limited. With this insight, we start to gain knowledge of how to control light to achieve a visible effect that we have in mind. It is, in fact, quite remarkable how the astounding range of human visual sensations is governed by so few processes.

Lighting is both the medium that makes things visible, and it is a visible medium. At one level, it reveals the identifying attributes that enable us to recognize the objects that surround us, and at another level it creates patterns of colour, and light and shade, which add other dimensions to the visual scene.

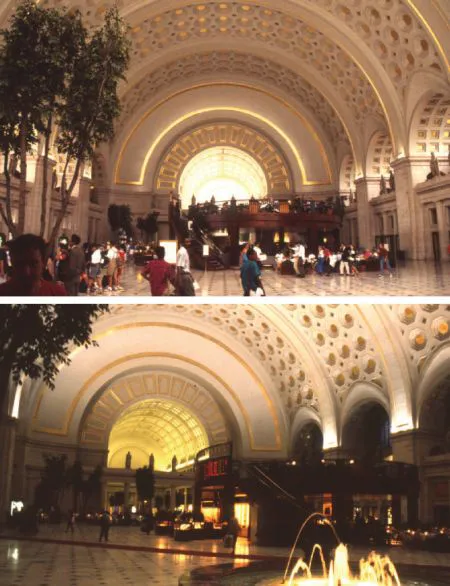

Facing page: Union Station, Washington DC. The 1988 renovation of architect Daniel Burnham's Union Station (opened in 1907) included new lighting designed by William Lam Associates. The uplighting in the Main Concourse is by two-to-one combinations of metal halide and high pressure sodium lamps, the sodium lamps having been added to cause the gold leaf decoration to gleam. This is effective both by day and by night, despite the vastly different overall appearance of the terminal

This chapter examines the role of lighting at the former level, that is to say, its role in making visible the aspects of appearance that enable us to perceive our surroundings. We start by considering what we need to know about the processes of vision and visual perception.

1.1 Visual constancy and modes of appearance

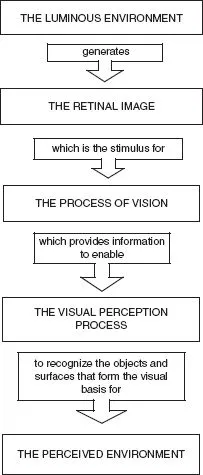

The underlying aim of lighting design is to control the luminous environment in order to influence the perceived environment. Figure 1.1 provides a simple model of visual perception, which shows that several stages are involved in making this connection.

Figure 1.1: A simple model of the human visual perception process. Lighting designers exercise operational control in the luminous environment, with the aim of influencing an observer's perceived environment. A complex series of processes occur between the designer's input and its effect

The luminous environment

This is the physical environment made luminous by light. It is here that the lighting designer exercises control.

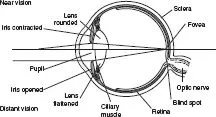

The retinal image

The optical system of the human eye focuses an inverted image onto the retina, shown in Figure 1.2. This image is constantly changing with movements of the head and the scanning movements of the eyes. It is often said that the eye is like a camera, but the only similarity is that it forms a focused image in which, for every pixel, there is a corresponding element in the luminous environment. The main difference is that the eye operates as an instrument of search. Unlike photographic film, the structure of the retina is far from uniform. High-resolution detection occurs only at the fovea, a small area of tightly packed photoreceptors, and except at very low light levels, resolution declines progressively to the periphery of the retina. While the relatively slow movements of the human body occur, more rapid movements of the head enable attention to focus onto things that have been noticed, while still more rapid movements of the eyes within their sockets cause objects of interest to be scanned for detail. The eye is not a picture-making device: it is the optical instrument of search that is actively involved in the process of seeking information of the surrounding environment.

The distribution of luminance and colour that comprises the retinal image is modified by light losses that occur in the optical media of the eye, and these losses are not constant as they increase significantly with age. Here we encounter an interesting conundrum. Because the retinal image is the stimulus for vision, we have no way of examining it. So, we are forced to accept measures of the luminous environment as practical indicators of the stimulus for vision, which means that we are by default assuming a notion of 'normal vision'. This notion presumes that those who need optical correction to achieve a sharply focused image will have it, and while allowance may be made for reducing image brightness with age, this is often overlooked in practice. This latter point is discussed in Section 2.2.

Figure 1.2: Sectional diagram of the human eye showing lens curvatures for near and distant focus. (Source: Coaton, J.R. and Marsden, A.M. (eds) Lamps and Lighting, Arnold, 1997)

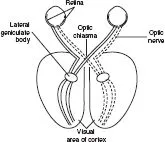

The process of vision

The purpose of the visual process is to provide an ever-changing flow of information to the visual cortex of the brain. The retinal image stimulates photoreceptors embedded in the retina, causing a series of minute electrical impulses to flow along the optic nerve pathways to the brain (Figure 1.3). It might seem more appropriate to compare the eye with a television camera than with the more familiar picture-making camera, but even here the comparison falls short. There are millions of photoreceptors in the retina, and processing of their responses occurs at several stages along the route to the brain.

The first level of processing occurs actually within the retina, enabling the optic nerve to transmit the visual information with far fewer nerve fibres than the number of photoreceptors. Further modification of the signals from the two retinas occur in the chiasma, where responses from both left-hand sides of the retinas are channelled to the left-hand lobe of the visual cortex, and the right-hand channel is similarly directed. Further processing occurs in the lateral geniculate bodies before the signals reach the cortex. While there is still plenty that is not understood about the working of these processes, much information on the performance of human vision has been gathered in recent years. The prime source of this information is studies involving measurements of the ability of an observer to detect small differences of luminance or colour, and this aspect of visual ability is discussed in Section 1.2. Its relevance to this discussion is that if an item of detail is to be part of the perceived environment, then its presence must be indicated by a visually detectable stimulus.

Figure 1.3: Schematic diagram of the binocular nerve pathways (adapted from Boyce, P.R. Human Factors in Lighting, Applied Science Publishers, 1981)

The visual perception process

The perception of a surrounding environment may be influenced by input from any of the senses, together with memory cues. Although vision is usually the dominant source of sensory information, the perception may be significantly influenced by inputs from other senses, such as auditory, olfactory, and tactile senses, together with memories derived from these senses. This simple model should not be taken too literally, as just how a perception of an environment is assembled from the signals that flow through the optic nerve pathways is much less well understood than the process of vision.

The perceived environment

This is the construct within the brain that serves as a model for the physical environment, and it has two distinct roles. It is within this mental construct that a person orientates and makes operational decisions, such as how to navigate through the space without colliding with furniture or other objects. Also, the mental construct represents the person's assessment of their environment. If one person finds a space pleasant and another does not, then we can assume that the perceived environments that each of them has formed are different. While some interpersonal differences are inevitable, it is evident that there are broad similarities which enable designers to satisfy both select and random groups of people. Luminous environments can be created that lead to a majority of sighted people generating perceived environments that both enable satisfactory levels of operational decision-making, and which also provide for positive evaluations of their surroundings.

Referring back to Figure 1.1, we can use this model to set lighting design into context. The designer's objective is to bring to life a perceived environment that exists as a mental image in the designer's brain. The image comprises more than a view. Depending on the designer's philosophy, it is likely to incorporate subjective concepts which relate to evaluative responses to the luminous environment, which is to be achieved by applying lighting to a physical environment. This is the essential function that the lighting designer controls. The link between the luminous environment and the perceived environment is the chain of functions indicated in the basic model of visual perception.

Added to this, it is inevitable that past experience will influence an individual's visual perception of their environment, and this gives one more reason why we need to recognize that the luminous environment and the perceived environment are not the same thing. That we have incomplete understanding of how the visual perception functions operate is not an overriding deficiency, as we can employ observation to explore ways in which variations in the luminous environment influence the pe...