![]()

Cicero praises the natural advantages of the site of Rome (de Rep., 11). It is only 25 kilometres from the coast, and because of its river combines the advantages of a safe inland position with easy access to the sea. The river, rising in northern Etruria, also provided easy communications with the centre of Italy. An island in the middle of the Tiber facilitated the crossing, and the hills of Rome, especially the Palatine and Capitoline, offered good natural defence.

Tradition makes Romulus the first king of Rome and places the date of its foundation in 753 BC although there may have been settlements there before then. Archaeological discoveries of Iron Age huts on the Palatine hill confirm the statement of Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Ant. Rom., 1. 79. 11) who records that one of them still survived in his day and was constantly kept repaired (he wrote at the time of Augustus). According to tradition, during the reign of the seventh-century king Ancus Marcius, a wooden bridge, the Pons Sublicius, was built over the Tiber. The bridge had great significance in the early community and its maker was given the title of Pontifex (bridge-maker). The town was laid out according to religious rites within a sacred boundary, the postmoenium or pomerium (Varro, De Ling. Lat., V. 143). The earliest pomerium of Rome seems to have taken in only the Palatine and a generous space around so that the sacred area was almost a square (Tacitus, Annals, XII. 24). The original walls followed the line of the hill, but were soon extended to include the Capitoline. Under the later kings the city included the Caelian, the Velia, the Oppian, the Viminal, the Quirinal and the Esquiline hills, and, according to tradition, these areas were enclosed in a large circuit of walls by Servius Tullius in the sixth century BC. Fragments of a very old wall built of cappellaccio or local tufa have been found on the Viminal and Aventine hills and these may belong to this old circuit.

In the middle of the seventh century BC Rome was conquered by the Etruscans and was ruled by them for the next one and a half centuries. The Etruscans were responsible for the first truly monumental buildings in Rome, and carried out several important engineering projects such as the draining of the Forum, which at that time was still a swampy valley. The Romans profited greatly from their example, and the Etruscan contribution to later Roman developments in the field of architecture and engineering cannot be overestimated. The Etruscans too had developed a robust and individual style in art, although in their turn they were great admirers of Greek art and architecture. Thus, despite its individuality, Etruscan art bears the unmistakable stamp of Greek influence. This Greek background to Etruscan art is important as it helps to explain Rome’s ready acceptance of Greek artistic and architectural taste later on.

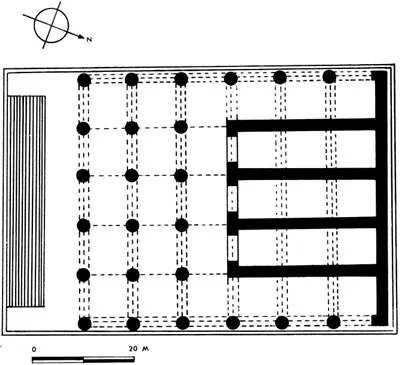

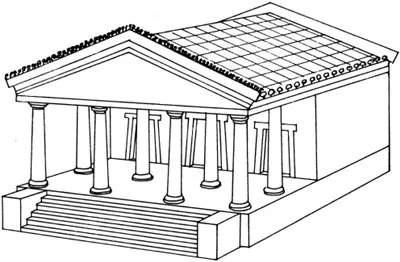

1 Rome, Capitoline Temple late sixth century BC, plan; (below) Restored view of a typical Etruscan temple

Roman temples and houses were closely based upon Etruscan models, and it is worth a closer examination of both of these. Etruscan temples usually rest on a podium, unlike Greek temples, and the emphasis is frontal. Simpler temples have a single cella with or without columns. The columns are normally only in front. More elaborate temples can have up to three cellas, side by side, and as much as half the ground area of the temple can be devoted to an elaborate columnar porch or pronaos. The huge Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline hill at Rome, which was being built by the last Etruscan king before he was expelled in 509 BC, is even more elaborate, with its three cellas and colonnaded wings (fig. 1). Parts of the substructure of the temple came to light in 1919 when the Palazzo Caffarelli was demolished. The surviving remains are a rectangular podium of tufa blocks measuring 62 × 53 metres. We know that Sulla brought columns from the temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens (see here) to use in the rebuilding of the temple following a fire which totally destroyed it in 83 BC. The height of the columns is 17.3 metres. This means that the columns are exactly one-third of the width of the temple, a ratio prescribed by Vitruvius (De Arch., 4.7.2).

Like other Etruscan temples its roof would have been decorated with rich terracotta ornaments. Architrave, frieze, cornice and sima were commonly sheathed in terracotta revetments with relief palmette and leaf ornament, sometimes pierced. Antefixes, often decorated with superbly imaginative heads or whole groups of figures, ran along the eaves. Sometimes full-size terracotta figures stood on the ridge of the temple, like the famous Apollo which formed part of a group on the roof of the Portonaccio temple at Veii.

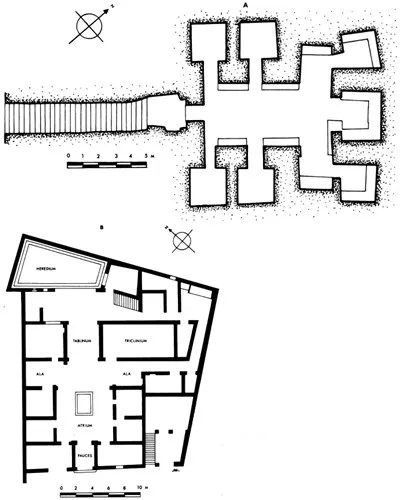

As for domestic architecture, most of our evidence for large Etruscan houses comes from tombs, which were modelled on the layout of a house. From this evidence we may infer that a large Etruscan house had a number of rooms grouped around a central hall. The tomb of the Volumnii at Perugia has a layout very reminiscent of atrium houses such as the House of the Surgeon at Pompeii (fig. 2). Instead of the doorway and fauces (entrance passage) there is a staircase leading down into the tomb. The main rooms are grouped around a hall or atrium with a beamed ridged roof. Opposite the doorway is the tablinum, or main room of the house, with a richly coffered ceiling. Note that the layout of rooms, as in many Roman houses, is symmetrical.

2 (a) Perugia, Tomb of the Volumnii, second half of the second century BC: plan;

(b) Pompeii, House of the Surgeon, fourth/third century BC: plan

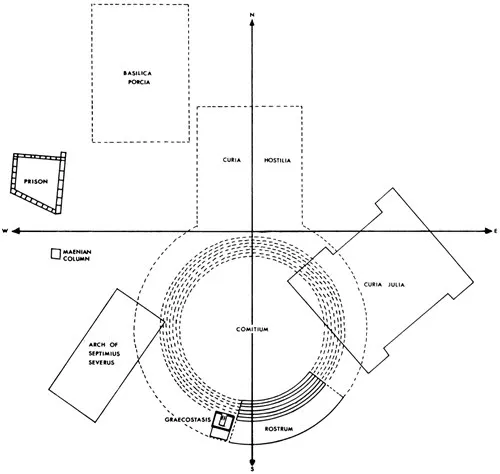

3 Rome, Comitium. A possible reconstruction showing the position of the Curia Hostilia

With the expulsion of the Etruscan kings Rome was free to shape her own destinies. The new Roman Republic was governed by elected magistrates and a Senate. There was also a popular assembly or Comitia with limited powers. The civic life of the new state was centred on the Forum (fig. 28). The earliest Republican temples included the Temple of Saturn (498 BC) and the Temple of Concord (366 BC). Other early buildings were the House and Temple of the Vestals and the Regia, the official residence of the Pontifex Maximus. The Forum was also full of small shops (tabernae). To the north-west was the old Senate House, the Curia Hostilia, which was the council-chamber of the Senate from a very early date. In the space in front of it was the meeting place of the people, the Comitium, and the speakers’ platform, the Rostra, called after the ships’ prows that were hung there after the Battle of Antium in 338 BC.

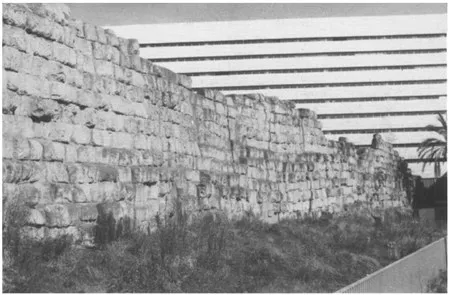

4 Rome, so-called ‘Servian wall’, c. 378 BC

The exact shape of the Comitium and its relationship to the Curia Hostilia have long been matters of dispute. Pliny (Natural History VII. 212) tells us that midday was announced by an official standing in front of the Senate House when he could see the sun between the Rostra and the Graecostasis (a platform from which foreign ambassadors, mainly Greek, addressed the Senate). The final hour of the day was announced when the sun sloped from the Maenian column to the prison. As the position of the Rostra and the prison is known, the location of the Curia Hostilia can be worked out (fig. 3). Other evidence suggests that the Comitium was circular with steps all round, and that the steps of the Comitium gave access to the Curia.

The new Republic soon became the dominant power of the region and even turned its arms against Veii, its Etruscan neighbour to the north, which fell in 396 BC. However, the Gallic invasion of 390 BC in which Rome was overrun and devastated was a setback. To protect the city against future disasters of this kind the Romans built a massive defensive wall, known as the ‘Servian wall’. The attribution is certainly erroneous as it is built of Grotta Oscura Tufa and must date to the period after the Roman conquest of Veii. The wall, laid in uniform blocks of 177 cm × 59 cm × 59 cm, has a total circuit of 11 kilometres. For most of this distance it followed the edges of the hills, but along the flat section of ground on the Esquiline, near the modern railway station, an agger or sloping mound 42 metres wide had to be built for a distance of 1,350 metres (fig. 4). The mound was contained between two walls, the inner being only 2.60 metres high and the outer about nine or ten metres high. Beyond the outer wall was dug an elaborate ditch, 36 metres wide at the top and about 12 metres deep. This impressive piece of fortification reminds us of the great engineering skill the Romans had already acquired at this early stage.

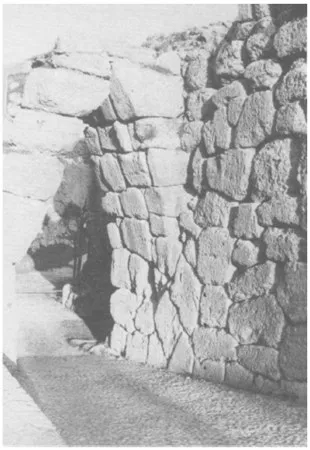

5 Arpinum, polygonal walls, c. 305 BC

During the fourth and third centuries BC, as Rome’s power spread over Italy she consolidated her conquests by a network of colonies and garrisons with vast and imposing fortifications. In the hills the walls took advantage of natural defensive features and were constructed of massive polygonal blocks of local limestone, for example at Circeii, Norba, Arpinum (fig. 5), Alatrium and Ferentinum. Where tufa was available, for example at Ardea and Falerii Novi, the blocks were well-cut and looked more like the ‘Servian Wall’ at Rome. Colonies on the plain, like Pyrgi, Ostia and Minturnae, were laid out within rectangular wall circuits, while towns like Cosa had a regular grid plan within an irregular wall circuit. Ostia will be more fully discussed later on (see Chapter 6), but Cosa is such a complete example of an early Roman colony that it is worth looking at more closely.

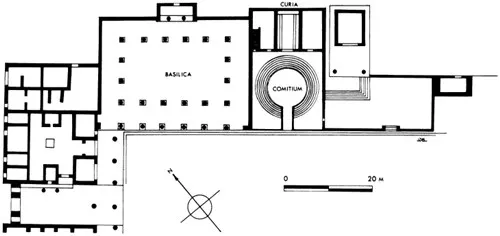

The town, laid out in 273 BC, is roughly trapezoidal in shape. It is enclosed by two kilometres of polygonal walls. The two highest points, one to the north and one to the south, are the sites of the most important temples. On the higher point stood the Capitolium (built 175–150 BC). In style it must have been similar to the old Etruscan temples, with its high podium, three cellas and a deep tetrastyle pronaos which takes up approximately half the ground area of the stylobate. The roofline particularly must have been reminiscent of Etruscan temples with its rich terracotta revetments and overhanging eaves (fig. 1). The long, rectangular Forum seems to have been completely surrounded by buildings in the later second century BC (fig. 6). On the north-east side stood a most important group of public buildings. The circular Comitium surrounded by steps seems to date from the earliest building period (270–250 BC). Behind the Comitium is a rectangular building which has been identified as the Curia. Access to the Curia was by way of the steps of the Comitium, an arrangement which may imitate that in Rome.

6 Cosa, buildings on the north side of the Forum, showing the basilica and Comitium. Plan as it appeared in the late second century BC

At Paestum, which became a Roman colony in 273 BC, a similar circular building surrounded on all sides by steps has been found, facing a rectangular forum like that of Cosa. It has been suggested that this too may have been a Comitium modelled on that at Rome. Next to the Comitium is a temple with an Italo-Etruscan ground plan. It has a high podium, steps at the front and a deep columnar porch. The columns also run along the sides of the temple, but not around the back. It has a single cella. It is thought to have been built shortly after the foundation of the colony, but remodelled about 100 BC with unorthodox Corinthian capitals supporting a Doric entablature.

During the fourth century BC the Romans still built lintelled or corbelled gateways, as at Arpinum (fig. 5), but by the third century BC they began to use the arch. It was not a Roman invention. Probably of eastern origin, it was making a tentative appearance in Hellenistic and Etruscan architecture by the fourth century. A fine early example of a voussoir arch (or arch made of separate stones) can be seen in a late fourth-century gateway at Velia. The first voussoir arche...