![]()

1

Beliefs

Belief … does not exist in an abstract, discursive space, in an empyrean realm of pure proclamation, “I Believe.” Belief happens in and through things and what people do with them.

David Morgan, The Sacred Gaze, 2005, p. 8

This book seeks answers to two fundamental questions of human history. The first question concerns that which some use as a defining element of humanity: religious beliefs. Why do so many people believe in supreme beings and holy spirits? The second question concerns the relationship of those beliefs to history in terms of cause and effect. Does history cause beliefs, religious and otherwise, such that we and our beliefs are shaped by the times in which we live? Or do our beliefs change history?

Both of these questions logically lead to more, refined interrogations, such as those surrounding the Mississippian civilization of ancient North America, the focus of my attention. Are religious beliefs more resilient than others? If so, why? What makes any belief or experience religious? Many might look to philosophy or psychology for answers to such questions. But in so doing they often retrace explanatory pathways previously trod by others. And they may be overlooking the insights that come from examining the intersections of human perception, memory, the physical properties of things, and the movements of non-human bodies in space. Archaeology is the study of such intersections, and questions about beliefs can be answered through archaeology by adapting newer theories of agency and religion that draw, in turn, on relational, animist, phenomenological, practice-based, and non-anthropocentric notions of relationships, social fields, and landscapes (e.g., Alberti and Bray 2009; Ingold 2011; Johnson 2007; Knappett and Malafouris 2008).

To some extent, these theories parallel aspects of cognitive theories of religion, particularly the focus on animist sensibilities and practices (Guthrie 1980, 1993; Lawson and McCauley 1990; Saler 2009). That such sensibilities and practices are contingent on processes of human cognition is likely. But archaeologies of religion are able to focus more on ritual and the experiential aspects of beliefs (Fogelin 2007, 2008). Some of these archaeological approaches, such as the one espoused herein, posit that agency is not the same as human intentionality and that religion is not simply a set of canons or theoretical platitudes held in the mind. On the one hand, people may be cognizant of what they do without intending anything in particular. On the other hand, the supernatural associations, beings, and rituals of religion pervade all kinds and levels of social life, especially for ancient Americans. Religious beliefs and experiences may be distinguished from other beliefs and experiences but possibly not because they are qualitatively distinct from non-religious ones. Rather, they are more extreme versions of all beliefs and experiences.

So too are the lines between agency and religion blurred in the experience of living and being. In large part, this is because other beings, things, substances, places, and forces might also be more or less agentic, which is to say that they might possess more or less causal power to shape history (cf. Gell 1998; Giddens 1984). Their agency is always partial and contingent on the web of relationships that define them. Ritual objects, places, or people can call forth certain emotional states, sensibilities, or memories. Bodily exertions, chants, and ingested substances can induce visions and, possibly, altered plans of action. A massive earthquake in America’s heartland in 1811 turned many toward their gods. A great meteor shower in 1833 did likewise, and induced a Mormon migration. A radio broadcast of a supposed Martian invasion in 1938 led to mass hysteria (see Cantril 1941). Even a rising full moon or a passing comet might entail a mass movement of people under the right circumstances (Hartwell 2007; McCafferty 2007).

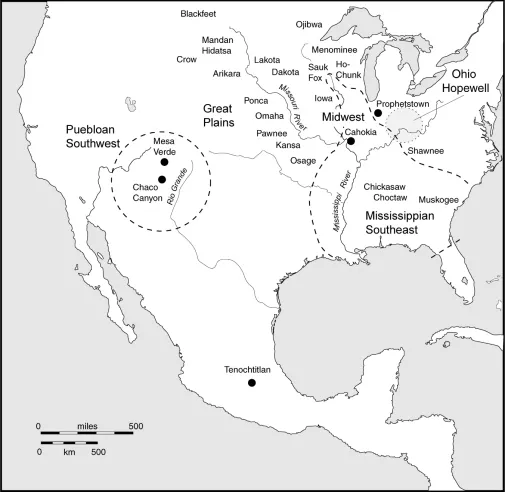

Such broadened views of agency that elevate the significance of earthly and celestial happenings bring us to the doorstep of religion, that amalgam of practices whereby people associate and align themselves with the cosmos and its otherworldly powers. We can understand this intimate association of agency and religion by studying how relationships between people, places, and things were bundled together and positioned in ways that constituted the fields of human experience. In this book, I develop such notions of bundling and positioning through archaeologies of agency and religion based, in turn, on case material from pre-Columbian and early historic-period North America. Much of this material derives from the Mississippi valley and Great Plains, especially the nine-century-old American Indian city of Cahokia. But I also draw to limited extent on the pre-Columbian and historic-era American Southwest and Ohio valley (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Map of ancient North America, showing archaeological complexes and historic-era tribes mentioned in the text

With regard to religion, I must hasten to add that this book does not focus on delimiting the boundaries of a discrete orthodoxy, or even a series of formal religions, as exemplified by other books on the “archaeology of religion” (Hinnells 2007; Insoll 2011). Various ancient indigenous North Americans did, of course, practice religion, by which I mean the ritualized venerations of mystical cosmic powers. But it is difficult to encapsulate and translate that religious practice into a written account. Indeed, I remain dubious of some contemporary attempts to do just that by purporting to read the meanings of symbols, imagery, art, and iconography as if there was one homogeneous and static belief system knowable to any contemporary analyst. Such attempts at reading the past, some based in normative and structural points of view, end up colonizing the past (Chapter 2). They do not allow the people of the past to speak, as it were, for themselves (Pauketat 2011). Instead, they appropriate the diversity of ancient beliefs—as lived in divergent ways by men, women, and children—and generate a single narrative understood only by the analyst.

Such scholarly appropriations of meaning also inhibit archaeological recognition of the religious causes of historical change (see Chapter 2). This is because religions are not merely sets of beliefs held in the collective consciousness of people and expressed through written words, images, or icons, awaiting clever archaeologists to read them like Rosetta Stones. Rather, beliefs “happen,” as Morgan (2005: 8) notes in the epigram, “in and through things and what people do with them.” Beliefs have a form, a materiality, and happen in space and time, on the land, and in the sky. They can be sensed—seen, heard, smelled, felt, and tasted—and have an emotional impact upon the people involved. They do not reside anywhere intact and complete. They exist only as an ever-changing web of relationships.

Dismissing Beliefs

I offer in these pages a way of rethinking theories of agency and religion. Like religion itself, I heavily reference the celestial realm via archaeoastronomy. Indeed, this book is partly a personal discovery of archaeoastronomy. Believe me, this has been as much a surprise to myself as it might be to those who thought they knew me. Of course, that’s what religious conversions do—they change you. And as a self-proclaimed minor prophet in a world full of diverse opinions and practices, my job here is to take up the mantle and proselytize you, the reader. Ultimately, my purpose with this book is not to create a full-blown archaeological religion. In this single book, I could not and do not aim to provide all of the necessary support for every point. Certain archaeoastronomical alignments posited in Chapter 6, for instance, remain untested and approximate. I am also less than comprehensive when it comes to all of the various astronomical bodies that might have been important to Native Americans. Indeed, I barely mention some stars, constellations, or celestial happenings—the Pleides, Venus, the dippers, supernovae, comets, or the Milky Way—that were undoubtedly of great importance to ancient people.

Of course, much of what passes as evidence in archaeoastronomy is highly questionable. The best archaeoastronomers—who tend to be professional astronomers (unlike myself)—are also the most suspect of such archaeoastronomical evidence (see Aveni 2001; Ruggles 1999). Some of them will (and perhaps should) remain unconvinced by my own attempts here. Certainly, in the recent past I would routinely brush off almost all archaeoastronomical argumentation with a dismissive wave of the hand: That’s nice but so what? Up to 2007, I was singularly concerned with answers to the proximate questions of human history: How did something happen in this place or that? I was not sure that ultimate questions—the big why questions of human history—were answerable through archaeology. Why do people believe anything? Why do they build square houses, tall monuments, or cities? Why do they accommodate social inequality or pay taxes to administrators? Why do some identify intimately with a leader, place, or thing, while others hate them?

And so, in 2001, I considered what archaeologists should be seeking to explain about the past, building on practice theory (and lumping the preferred approaches together as “historical-processual”):

In the new historical-processual archaeology, what people did and how they negotiated their views of others and of their own pasts was and is cultural process. This relocation of explanation may deprive archaeologists of direct and easy access to the ultimate why questions that we like to think we can answer. But in so doing, we will cease deluding ourselves that we can know – especially with our present limited databases – the ultimate truths behind complex histories.

(Pauketat 2001: 88)

But this was before a second excavation season at an extraordinary archaeological site near the ancient city of Cahokia (see Chapter 7). In 2007, my crew, students, and I returned to a site where we had previously uncovered an enigmatic temple and a series of pole-and-thatch houses and associated deposits. A linear depression on the floor of the temple proved especially problematic (see Chapter 8). But by 2007, I had begun to align the facts: the seemingly inexplicable patterns seemed to parallel astronomical phenomena. I had begun to get religion (the ancient sort). Of course, my religious conversion runs headlong into the deeply entrenched beliefs of others.

Many will remain dubious of any argument that includes appeals to the moon or other celestial objects and asterisms. There remains a pervasive Western, rationalist bias in archaeology that predisposes some researchers—even those who advocate various social-archaeological, landscape-based, or post-colonial approaches—to be suspicious of inferences about patterning that suggests cultural order and alignments realized at scales larger than the immediate and everyday. Such thinking goes beyond the inferences about human intentionality and choices with which they are comfortable.

This inability to think beyond intentionality and choice is particularly pronounced among historic archaeologies in North America. Understandably, some worry about researchers who might superimpose their own astronomical vision on the past, in much the same way that I worry about those who reconstruct ancient religions. But, I contend, such dubious researchers also frequently underappreciate the degree to which either their theories of practice, performance, phenomenology, and agency or, as likely, their local excavations of houses and individual sites prioritize “everyday practice” in biased ways rooted in the consumerism and alienation of modernity. We need to rethink agency and religion.

Other archaeologists also do not like theorizing at such high levels of abstraction (as in analyzing agency and religion). Many of them are content with small-scale hypothesis testing and avoid big-picture explanations (although they may think themselves more scientific than those who might dabble in theories of agency and religion). Their scientific precepts tend to be located in the realm of commonsense.

QUESTION: Does it matter if ancient people believed that seemingly inert things possessed a spirit?

COMMONSENSE ANSWER: No, they were thoughtlessly perpetuating an ancient tradition with little historical effect.

QUESTION: Why did people build Chacoan Great Houses, Hopewellian mounds, or the city of Cahokia?

COMMONSENSE ANSWER: There must be an adaptive reason for such behaviors; undoubtedly a perceived economic need or benefit was recognized in advance, and Chaco, Hopewell, and Cahokia were built in response.

Researchers who answer in such ways may believe that their logic is somehow more robust than the theoretical constructs of those who seek to interrogate agency and religion. But, contrary to what they might believe, their answers are not more scientific. In many cases the opposite is true. Their views are beliefs about science rooted in a modern rationality that fails to appreciate the alternate ontologies—the theories of being—of ancient worlds. Those theories were relational and animistic, recognizing the interrelatedness of life and the lack of clear boundaries between animate and inanimate things, places, and substances.

A scientific archaeology of religion, if such a thing be allowed, does not seek to reconstruct beliefs nor does it reject religion as if peripheral to explanations of the past. Rather it attempts to understand how religion—as performed in the open, practiced on the landscape, and experienced in and through things, elements, and substances—was related to human history. Call it hubris but, in hindsight and with sufficient empirical data, I do believe that archaeologists can answer the big why questions of human history. Some of these are to be found by rethinking agency and religion and by approaching relational ontologies via a theory of bundling and its related concepts (translation, transference, transubstantiation, positioning, alignment, and hierophany). My reformulation of our understanding of agency and religion in the past, using those data and via such theories, should lead one to answers.

Plan of the Book

To reach such heady conclusions, I begin in the next chapter with a historical introduction to some traditional ways of thinking about religion, with the help of two prominent early 19th-century Native American leaders, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, and their Shawnee politico-religious movement. The focus there is on delineating how certain past approaches in archaeology have constrained our approach to ancient religion. These have been labeled “representational” and subsume everything from the idealism and functionalism of the early 20th century to the materialism of the late 20th century and the structural approaches popular in some archaeological circles today (Barrett 1994: 155; 2000). All of these assume that cultures and cultural materials are the results, not causes of the beliefs and behavioral processes which they then merely reflect or represent. I use Mississippian culture and religion to illustrate the problems of locating belief only in the mind.

In Chapter 3 we begin to move toward more relational, historicized, and phenomenological approaches to understanding religion, largely developed in archaeology via considerations of human agency. The broad issues underlying these considerations involve causality. Archaeologies of agency and religion have perpetuated the errors of older approaches. Newer animist, phenomenological, neuro-phenomenological, and practice-based applications permit us to recognize the inseparability of religion and agency as these were manifest in material culture, interactive space, and all other aspects of social life. These newer approaches are part of theories of bundling and entanglement that emphasize relationships over agents, the former as defined via motions and experiences in social fields of beings and things, and the latter as afforded by particular intersections of these web-like networks, what Tim Ingold (2007b, 2011) now calls “meshworks.”

Such a theory resonates with the cultural practices of North America’s indigenous people. In Chapter 4, I examine these practices, specifically via the ethnohistory of American Indian medicine bundles, those carefully wrapped and curated sets of prized, magical, or ritual objects that defined one’s identities and enabled one’s relationships to all of the causal powers of this world and the next. In the past, these bundles were both cultural metaphors and agents of change in their own right. They remain so today.

Chapter 5 begins to consider bundling at a larger scale of analysis, that of the cosmos. Here, we see in broad outline how people have intimately connected themselves and their environs to the heavens, especially the moving celestial bodies in the sky: the sun, moon, planets, and stars. The illustrative material in this chapter derives from the North ...