eBook - ePub

Management of Knowledge in Project Environments

Peter Love, Patrick Fong, Zahir Irani, Peter Love, Patrick Fong, Zahir Irani

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 256 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Management of Knowledge in Project Environments

Peter Love, Patrick Fong, Zahir Irani, Peter Love, Patrick Fong, Zahir Irani

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Management of knowledge in project environments is a unique text that brings together contributions from leading academic practitioners, to demonstrate how the management of knowledge can lead to project success in today's complex and changing business environment. The work examines how the management of knowledge, particularly the sharing of knowledge and the importance of learning through reflection, can lead to project success and improved business performance. This book is written by an international contributor team and offers practical applications, models and case studies from a variety of international perspectives.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Management of Knowledge in Project Environments un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Management of Knowledge in Project Environments de Peter Love, Patrick Fong, Zahir Irani, Peter Love, Patrick Fong, Zahir Irani en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Business y Business General. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Chapter 1

Conceptualizing and implementing knowledge management

Introduction

Knowledge management (KM), in many ways, is more of an art than a science (Liebowitz, 1999). Knowledge management is the process of creating value from an organization’s intangible assets. Simply put, KM refers to sharing and leveraging knowledge within an organization and outwards toward customers and stakeholders. According to Liebowitz (2004), however, many organizations do not have a systematic approach to sharing and leveraging knowledge internally and externally.

In any growing field, the art often precedes the science until various methodologies, techniques, processes and tools are developed to underpin the field. This has certainly been the case with KM, as there has been a blurring of the true meaning of data, information, knowledge, expertise, wisdom and beyond (Liebowitz, 1999). In addition, the early contemporary works in KM promised improved knowledge-sharing techniques to increase innovation, improve customer service, retain expertise and enhance learning. As a result, many organizations appointed chief knowledge officers or chief learning officers to develop a KM strategy to spearhead knowledge initiatives. Several organizations, such as Dell and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), preferred a codification approach, which emphasizes a systems approach to capturing and sharing knowledge, often emanating from their information technology (IT) department. Others, such as Hewlett-Packard, Hallmark and the US Federal Aviation Administration, felt that a personalization approach to accentuate people-to-people connections was a better fit for their organization (Zack, 1999). Often both approaches have been used by organizations, but one generally dominates.

Knowledge management has such strategic value that organizations should include it as one of the key pillars of their human capital strategy (Liebowitz, 2004). Liebowitz (2004) suggested that KM strategy should be used to complement other strategic initiatives such as competency management, performance management and change management. It has been estimated that about half of the Federal civil servants in the US government are eligible to retire in the next five years, about 71 per cent of whom are senior executives (Liebowitz, 2004). In the coming years in the US government, there will be a severe knowledge bleed effect resulting from retirements. Knowledge management can play a significant role in addressing some of these human capital concerns (Liebowitz, 2004). Knowledge management can help to capture, share and leverage knowledge before it leaves the organization. Newly appointed chief human capital officers in the US government have undertaken the task of developing human capital plans for their agencies (Liebowitz, 2004).

A key question is whether KM will be the ‘management fad of the day’, and fall peril to the demise similar to business process re-engineering efforts. It has been estimated that about 70 per cent of business process re-engineering efforts have been failures in organizations (Love and Gunasekaran, 1997). Many people feel that KM may also become a similar victim if science and rigour in the discipline are not accomplished (Liebowitz, 1999). Knowledge management sceptics believe that knowledge cannot be managed; however, there are those who believe that it is possible to manage the environment in which knowledge exists. Others, such as Davenport and Glasser (2002), have suggested that KM is too amorphous, although it has an excellent altruistic value; however, the returns on investment for KM efforts are difficult to calculate. Liebowitz (2004) has suggested that KM is often viewed as being a ‘no brainer’ philosophy that is adopted by businesses; that is, taking advantage of learning what others know and have experienced is essential in today’s competitive, fast moving, global environment.

Thus, a mystique of doubt and optimism surrounds KM. Part of this mystique is attributed to the evolution of the field as it develops. Certainly, to convert the doubters to believers, there must be a great degree of rigour imparted into the KM field. This chapter will examine some of these areas, and will suggest how KM can form an integral part of an organization’s fabric and strategy for managing projects.

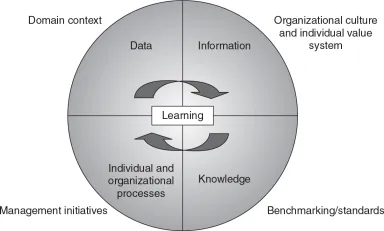

A knowledge framework

A framework that organizations can use to conceptualize KM is presented in Figure 1.1. Here, data refer to discerned elements, and when processed or patterned in some way, they are transformed into information. Once the information becomes actionable, it is transformed into knowledge. When knowledge is then learned and embedded into individual and organizational processes, the value of knowledge to the individual and organization increases in worth. The environmental factors affecting this knowledge cycle relate to domain context, organizational culture and individual value system, management initiatives and benchmarking/standards. Knowledge must have context if it is to be useful to an organization. In addition, the promotion or inhibition of knowledge will be affected by the organizational culture, as well as the individual’s value system. How knowledge is internalized and then externalized is related to an individual’s worldviews. Management initiatives and standards will also affect the creation of knowledge in the organization.

Figure 1.1 Conceptual view of the knowledge framework.

Suppose a project manager is currently concerned with testing a satellite that their team is building, for possible vibration problems. The project manager could receive some test data showing the results of the vibration testing experiment. By looking at some of the trends in the data, various patterns could be revealed (i.e. information). By examining these patterns, the project manager decides also to consult an available organizational ‘lessons learned’ database and discovers that a previous satellite experienced the same types of vibration testing problems that their satellite is experiencing. The project manager acts on this new information through their knowledge to determine the criticality of the testing results and what should be done to resolve these problems. At this point, this information is transformed into knowledge. As this knowledge is shared with others, either via word of mouth or through the lessons learned system, this knowledge will be embedded into the working processes of future project teams involved with testing.

The domain context in this example deals with satellite vibration testing. Certain standards are typically used to ensure the ‘safety and health’ of the satellite. If the organizational culture lacks a pervasive knowledge-sharing flavour, then the creation and exchange of vibration testing knowledge may be at risk of not being codified and transferred to other project teams that need these lessons learned. However, if the organization promotes the active capture, analysis and dissemination of lessons learned, then those project teams involved with vibration testing will be better informed. Coupled with the organizational culture and climate, the synergistic effect of management initiatives could influence how the knowledge is shared throughout the organization; that is, if there are competing management initiatives that shift work priorities on a frequent basis, then there may be more risk of not capturing and sharing the necessary knowledge with all appropriate project teams.

Knowledge is often gained through experience. Experiential learning typically generates rules of thumb (heuristics). These rules of thumb are pieces of knowledge that can be in the form of lessons learned, anecdotes, cases, rules, guidelines or the like. In the project management or business environment, a general rule of thumb may be to take an estimate for the software development schedule and budget and double it. In the university setting, a rule of thumb is never to miss the first committee meeting. Usually the chair of the committee is selected at the first committee meeting of the year, and whoever is absent is unanimously selected as the chair (mainly because most people prefer not to have that responsibility and added workload).

Knowledge without context is futile. For example, Americans enjoy having a ‘comfort zone’ or personal space when speaking to others. Comfort zone refers to the physical distance between a person and others when speaking at an informal gathering (Kramer, 2001). In Asia and Latin America, the intimate distance or personal space is much closer than that in the USA. These cross-cultural differences influence the universality and generality of applying knowledge. These cross-cultural differences also impact the management of projects in organizations, as international team members must respect each other’s culture and customs, yet are able to move the project along within time, cost and schedule constraints. For example, NASA often works with international partners on space projects, so having the ability to respect each other’s practices is a necessity. Hence, context is an important part in producing knowledge.

Knowledge can be distilled from successes as well as failures. In project management, lessons learned and best practices abound. For example, NASA has a Lessons Learned Information System (LLIS), which has over 1300 lessons relating to project management, systems engineering and other areas. NASA project managers are now required to capture, access and apply lessons learned from the LLIS to their projects. Both successes and failures should populate a lessons learned repository to allow knowledge to be internalized and created in the context of various project environments.

The knowledge management cycle

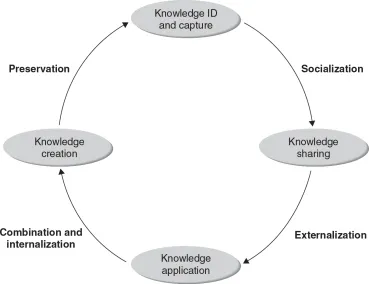

The KM cycle consists of four major stages, as shown in Figure 1.2, and is used to support the framework presented in Figure 1.1. Knowledge is identified and captured, shared with others, applied in combination with existing pertinent knowledge, and then created in the form of new knowledge, which is then captured and continues as noted in Figure 1.2.

Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) Socialization–Externalization– Combination–Internalization (SECI) model can be included as part of the KM cycle. Once key knowledge has been identified and codified in some way, a socialization effect occurs resulting in knowledge sharing. Knowledge resulting from this knowledge-sharing experience becomes externalized, resulting in an application of the knowledge. This knowledge is then combined with other knowledge that the individual possesses, as well as internalized along with the individual’s worldviews and value hierarchy. This should hopefully result in new knowledge being created, which then needs to be preserved as it becomes captured and the cycle begins again.

Figure 1.2 The knowledge management cycle.

Knowledge management strategy and implementation

Now that a KM framework has been built, we can better understand how to develop a KM strategy and resulting implementation plan. Several researchers and practitioners have been studying techniques and methodologies for developing KM strategies and implementation plans (Apostolou and Mentzas, 2003; Liebowitz and Megbolugbe, 2003). According to Chourides et al. (2003), for KM to be successful, an organization must have a strategy and individuals must be persuaded to contribute to its formulation and implementation. The KM strategic plan has greater focus on the knowledge needs of the organization and an evaluation of capabilities. Apostolou and Mentzas (2003) developed the Know-Net KM approach, which includes the interplay among strategy, assets, process, systems, structure, individuals and teams, across organizations and within the organization itself. They use a systems thinking approach to KM that looks at the interlinking, feedback and control between these areas. Similarly, Sveiby (2001) discusses his knowledge-based theory of the firm and indicates nine important knowledge strategy questions:

- How can we improve the transfer of competence between people in our organization?

- How can the organization’s employees improve the competence of customers, suppliers and other stakeholders?

- How can the organization’s customers, suppliers and otherstakeholders improve the competence of the employees?

- How can we improve the conversion of individually held competence to systems, tools and templates?

- How can we improve individual competence by using systems, tools and templates?

- How can we enable the conversations among the customers, suppliers and stakeholders so they improve their competence?

- How can competence from the customers, suppliers and other stakeholders improve the organization’s systems,tools, processes and products?

- How can the organization’s systems, tools, processes and products improve the competence of the customers, suppliers and other stakeholders?

- How can the organization’s systems, tools, processes and products be effectively integrated?

O’Dell et al. (1999) performed benchmarking studies on KM strategies. They found organizations using KM strategies as a matrix of KM as a business strategy, transfer of knowledge and best practices, customer-focused knowledge, personal responsibility for knowledge, intellectual asset management, and innovation and knowledge creation. In project management terms, the work of O’Dell et al. implies that successful project teams need to have a shared vision for the project, as well as a sharing of responsibilities to achieve the project’s goal. Levett and Guenov (2000) developed a methodology for KM implementation that looks at a four-phase approach of case-study definition, capturing KM practice, building a KM strategy, and implemention and evaluation. April (2002) developed guidelines for building a knowledge strategy looking at the interlinking of assets or resources, complementary resource combinations and the strategic architecture of the company. Nickerson and Silverman (1998) examined intellectual capital management strategies and proposed a strategy integration analysis methodology that uses six steps: assemble a multidisciplinary team, identify and select a target market and position, identify investments and technology, identify unique or idiosyncratic technologies that form the basis of competitive adv...