CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Hans-Georg Gadamer was one of the most prominent European thinkers of the twentieth century. His philosophy is above all dedicated to discovering the most general patterns of experience and thinking that occur whenever people seek to understand the world and one another, whenever they interpret texts or other expressions of meaning, and whenever they experience art or nature as intriguing, enjoyable, and significant. The pattern that Gadamer came to see running through all of these forms of experience he called “hermeneutic,” and he characterized his philosophy as “philosophical hermeneutics.” Today in many fields of study one can find theorists who take a “hermeneutic” approach to their subject, and in most such cases the influence of Gadamer can be recognized.

While Gadamer wrote little on the subject of architecture specifically, his writings on art and aesthetics are extensive, and they play a central role in his overall philosophical program. for this reason his thinking has, for decades, been influential on a variety of architects and architectural theorists. A hermeneutic approach to architecture discovers the hermeneutic pattern of thought and experience in several areas of the architectural enterprise. It may be found in the creative activity of the architect and the aesthetic appreciation of the architect’s creations. It may be found in the way architects seek to understand architectural traditions and writings on architecture. It may be found in the ways that all of those who collaborate in the architectural enterprise—the clients, the community, the developers, the regulators, and the designers—understand one another and work together. It is important to note that in all such cases the hermeneutic pattern is, Gadamer would say, inevitably at work. It is something that happens whether or not we intend it. But by realizing and acknowledging that the pattern is at work we may consciously and deliberately seek to follow the path that it opens for us.

“Hermeneutics” and “hermeneutic”

The root of the word “hermeneutics” is an ancient one referring to the activity of interpretation. Already in the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle, and in the writings of ancient rhetoricians, there occurred the question as to how people understand and misunderstand one another, and how words that are written down can be interpreted when the author is not present to be questioned in dialogue. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in europe, “hermeneutics” became an important subfield within the disciplines of law, theology, and modern rhetoric. Theorists in these fields sought to develop rigorous standards and techniques for determining how texts that were written in previous ages should be applied in contemporary circumstances. Religious scriptures and legal statutes, for example, may have been formulated in a very different time, yet they intend that their readers should live by them today. The documents are not merely of historical interest, but make real claims upon their readership. Hence the work of hermeneutics in these disciplines always combines understanding with practical decision and action (Gadamer 1990b, 324–34).

Gadamer claims that this quality of traditional hermeneutics—its combination of intellectual grasp and practical application—is at work in the interpretation of any text, and indeed in every instance of trying to understand the thoughts and beliefs of another person or culture. He holds that the hermeneutic dimension of understanding is universal (1976, 3–17). architecture, like texts, always functions, to some degree, as a carrier of cultural meaning. Dalibor Vesely has said this in a dramatic way: “what the book is to literacy,” he writes, “architecture is to culture as a whole” (Vesely 2004, 8). If there is an inevitable pattern of understanding that occurs whenever a work of architecture is interpreted, should the architect not have a sense of how that pattern unfolds? If architecture itself interprets a culture, would it not benefit the architect to examine the pattern by which architecture forms such an interpretation? If buildings from the past, like books from the past, have a continued relevance for the present, should the architect not ponder the pattern by which that relevance is achieved? Hermeneutics, in both the study of texts and in relation to architecture, holds the promise of fundamentally altering the way one thinks about interpretation, understanding, and the communication of culture.

Hermeneutics holds the promise of fundamentally altering the way one thinks about interpretation, understanding, and the communication of culture.

The hermeneutic pattern that Gadamer seeks to articulate has been called “the hermeneutic circle.” This idea does not originate with Gadamer. Already in the hermeneutics of the nineteenth century (which Gadamer calls “Romantic hermeneutics”) there was a sense that the interpretation of texts must move in a circular pattern. This circle is often characterized in terms of a relationship of parts and wholes: to understand the whole of a book it is necessary to grasp its individual words and sentences, but those words and sentences only have meaning within the larger context of the book, hence interpretation must be a matter of constant revision: revising one’s sense of the whole as one grasps the individual parts, and revising one’s sense of the parts as the meaning of the whole emerges. Thus the hermeneutic circle is not a vicious circle but a cumulatively productive one (1988, 68–78; 1990b, 190–91).

There is another, more subtle, way in which a hermeneutic circle is at work in such cases. When the philosopher and theologian augustine (354–430) explained how one should study the Bible, he recommended interpreting the more obvious passages first and then going on to make sense of the difficult and obscure passages in terms of the obvious ones (augustine 1958, 42–3). But practitioners of Romantic hermeneutics realized that what makes a passage obvious to a reader might be less a matter of its inherent transparency than a matter of the assumptions that the reader brings to the text. Moreover, because the passage seems obvious, one might be less inclined to question those assumptions than one might otherwise be. So the hermeneutic circle, in this light, must proceed by beginning with assumptions, but must then revise them as an understanding of the text deepens. Ultimately, one may come to see all of the obvious readings with which one began as misinterpretations born of naïveté and bias (Gadamer 1990b, 179–80; Schleiermacher, 1998).

Gadamer’s major philosophical work is entitled Truth and Method. The first word in this title is meant to suggest that the hermeneutic pattern is involved whenever one seeks truth. Here Gadamer deliberately echoes Plato. Plato used the word “dialectic” to refer to the general form of socratic inquiry that questions commonsense assumptions, seeks consistent definitions of terms, considers explanatory hypotheses, formulates arguments, considers objections, and refutes those objections or revises the theory in light of them. Dialectic can be undertaken with regard to any question or any topic, be it a question of nature, of morality, of politics, of religion, or of art. It can be pursued in good-natured discussion among friends, or it can be practiced in the privacy of one’s own reflections (Gadamer 1980, 93–123; 1990b, 362–9). Gadamer advocated the same kind of generality for his hermeneutic pattern that Plato claimed for dialectic. To make this point, Gadamer sometimes proposed dropping the “s” off of the end of the English word “hermeneutics” to show that “hermeneutic” has the same comprehensiveness and generality as dialectic, and goes together with dialectic.

“Method,” on the other hand, is something more modern and narrower in scope than either hermeneutic or dialectic. The notion of “method,” as it is commonly used today, was born of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment period, when thinkers were seeking to associate rationality with the investigative techniques of natural science. A “method,” in this context, identifies a limited set of questions to be asked, a limited range of evidence to be consulted, and a strict empirical procedure to be followed. A Newtonian discussion of the interaction of a set of billiard balls, for example, would be limited to questions of the physical forces by which they move and are moved; the evidence would be the observable interactions of the individual balls; the procedure might involve experiments that would isolate one kind of impact of one ball on another ball. Nothing would be said about the human interests of the people manipulating the cues or the about the game in which they are engaged. Never would the ultimate meaning of the movement of the balls or the value of the game come into consideration.

This narrowed form of investigation is of incalculable value within the limited scope of natural-scientific questions. The problem, however, is that Enlightenment culture began promoting this kind of rationality as the premier form while demoting all other forms. In the centuries since, as ever-increasing numbers of disciplines have sought to become “scientific,” it is not uncommon to hear natural-scientific rationality proclaimed as the only legitimate form of rationality. Gadamer, in contrast, resists all such narrowing of the ideal of reason. For most of human history there has been a belief that the arts and humanities promote crucial forms of rationality, forms that civilize us and justify our ethics, our laws, and our institutions of government. To denigrate or to lose those forms of rationality is to risk a dehumanized society. It is for this reason that philosophical hermeneutics aims at recovering, in a contemporary manner, a more generalized and broadly applicable notion of reasoning and its uses. The search for truth, Gadamer’s book title intends to suggest, is in some degree of tension with the idea of method (1984c, 151–69; 1990b, 3–9).

The search for truth, Gadamer’s book title intends to suggest, is in some degree of tension with the idea of method.

Philosophical hermeneutics and the aims of architecture

As the book is to literacy, says Vesely, so architecture is to culture. This cultural significance of architecture is what attracts many students to the field. They have a sense that architecture is not simply interesting or enjoyable, but is important to life. It can contribute, in its own way, to enriching a community and expressing that community’s significance. This dimension of meaning is part of what gives architecture an affinity to philosophy, but one need not be a student of either philosophy or architecture to understand, at some level, that architecture carries profound human meaning. countless tourists board airplanes every year to be awed by the world’s great buildings, gardens, and cities. In their visits to palaces, temples, and pyramids these people have a sense that they are not just encountering works of art, but expressions of the deepest cultural aspirations of a people. The great works of architecture compound many kinds of meaning and purpose into a single creation, and do so in an astoundingly integral way.

But how is architecture able to accomplish this? And how is it able to continue doing so through historical changes in style, technique, and materials? Such questions embroil us a complex set of issues within the field. Let us approach them simply by identifying four basic puzzles that characterize the discussion. A first of these would concern the matter of functionality. Architecture must be functional, and yet it should not be reducible to its functionality. A kitchen appliance may be called “wonderful,” and even “the perfect combination of utility and design,” but a building, even if it is a “machine for living,” is a disappointment if it is only wonderful in the ways that an appliance is wonderful. A building should signify more than that. This is not to say that buildings must be monumental or overtly representational. A humble structure can be highly communicative; an abstract style can be rich with suggestiveness. But the architect always faces the challenge of making a structure meaningful, or of relating the structure to traditions of meaningful building, while at the same time fulfilling contemporary expectations for functionality under the constraints of a budget.

Secondly, while architecture is certainly an art, its cultural significance involves more than its aesthetics. For most of human history this point has seemed fairly obvious. The beauty of a Gothic arch—the way it fashions stone into elegant and dramatic shapes—is not separable from its structural function of holding up the roof—nor, for that matter, from the symbolic meaning it communicates by pointing to heaven and making heavy stone seem to evaporate into the air. All of these qualities are thoroughly intertwined. But a number of writers on the history of architecture (and notably several who are familiar with Gadamer) identify trends beginning in the Baroque period that separate the aesthetic dimension from the structural underpinning. The beauty of the work, the way it pleases the senses, comes to be associated with ornament, and the structure becomes mere scaffolding for ornament. The first part of Gadamer’s Truth and Method gives an account of how this attenuated sense of the aesthetic came to dominate art criticism and the philosophy of art. The trend, for Gadamer, represents a weakening of the sense of the power and importance of art and architecture. Karsten Harries and Alberto Pérez-Gómez, drawing on Martin Heidegger and others in the european philosophical tradition, approach the issue in terms of architecture’s ability to embody a cultural ethos. The aestheticization of architecture’s sensuous qualities would seem to impair its ability to fulfill this “ethical” function (Harries 1997; Pérez-Gómez 2008, ch. 9; sharr 2007, 101–3). Vesely speaks, in a similar vein, of the division of architectural representation from its technological support as a conundrum for contemporary architects, something calling for a new integration (2004, chs. 4 and 5; Sharr 2007, 103–4).

The modern innovations of figures such as Adolf Loos, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Le Corbusier, and Louis Kahn represent daring efforts to reintegrate architecture in a radically new way, decrying superfluous ornament and seeking to draw out of the potentialities of new materials and engineering principles a meaningful vision of a thoroughly modern human community. But the realization of this modern vision has not gone entirely smoothly, with backlashes that include charges of social engineering, demands for historic preservation, and the emergence of various forms of “post”- modernism. It would be fair to say that the question persists as to how the aesthetic dimension can be reintegrated in a fully successful way with the other important qualities of architecture.

The question persists as to how the aesthetic dimension can be reintegrated in a fully successful way with the other important qualities of architecture.

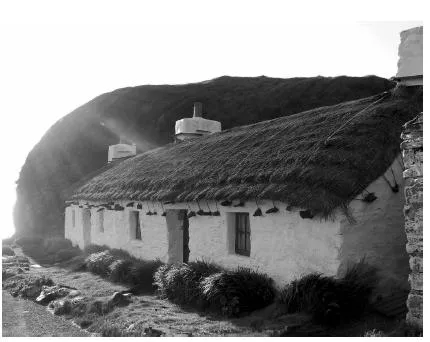

A third kind of puzzle has to do with the symbolic function of architecture. When we speak of the “meaning” of architecture, or when we follow, say, the approach of christian Norberg-Schulz in his classic survey Meaning in Western Architecture (1975), what is intended by the word “meaning” is primarily the symbolic dimension of architectural works. The most primordial of structures can possess commanding symbolic suggestiveness. The monolith or the stone circle may employ the most elementary of building technologies, and yet they align with the stars and track the seasons in ways that seem to connect the structures with the whole of the cosmos. To create settlements in a landscape is always also to symbolize the human relationship to that landscape. Many forms of local and traditional architecture, for example, identify with the environment by building with the materials that it provides, orienting the resulting dwellings to the topography, the light, and the climate patterns of the region. As human construction identifies with landscape, it simultaneously complements the landscape by symbolizing the ways that human life stands out from nature. The monolith and the tower, for example, announce, by their rising-up from the ground and their orientation to the sky, the human way of standing-out from the world of minerals, plants, and non-human animals. The civic gateway and the domestic threshold (to take another simple example) divide, both practically and symbolically, varieties of public space from the interiority of community, family, or the individual psyche (cf. Norberg-Schulz 1979; 1985).

Cottage at Niarbyl, near Peel, Isle of Man

Countless symbolisms of this sort can be elaborated, yet a host of questions accompanies the task. What, one may ask, does it mean, after all, to be a symbol? How does symbolism embody meaning? Of the many kinds of scholars who study symbolism—psychologists, philosophers, theologians, anthropologists, historians—who is best equipped to explain the symbols of architecture? Do the architectural forms that carry symbolism need to be representational? Do they need to be part of a narrative? If so, does this mean that a more abstract kind of architecture is also a less symbolic kind? And what about those architects who go about their work without giving a thought to symbolism? Is their work free of symbolisms or do they symbolize in spite of themselves?

In the fourth place, all of the features that I have been describing—the functionality, the artistry, and the symbolism—are shaped within history and traditions. In “traditional” forms of architecture this fact can be expressed in a straightforward manner: the building solutions and stylistic tastes were preserved and handed down as the legacy of a tradition. But to the extent that modernism made its project the overcoming of the limitations of the past, it raised new questions as to how modern styles should relate to past styles. The nature of modernism is not simply to invent new artistic conventions for a new age, but to keep endlessly innovating. An avant garde will constantly be reinventing everything, and the most prominent architects today are under pressure to keep reinventing themselves—as Picasso regularly did—resisting the repetition of even their own former creations. Yet at the same time there are those who consider the idea of stepping out of history and forming an utterly new age or a new humanity as regrettably naïve. The past has a power over us, it is argued, that runs deeper than our abilities to consciously master it, and to reject our origins in a totalizing way is to leave ourselves alienated and homeless. This is the dilemma of history, within which every architect must take a stand.

Gadamer’s hermeneutics is relevant to all four of these areas of questions and challenges for architecture. His efforts to recover ideals of rationality that are broader than empirical and technical reason parallel efforts in architectural theory to resist the reduction of architecture’s significance to its practical functioning. The distinctive understanding of the notion of “play” that Gadamer develops in the first chapters of Truth and Method goes a long way toward integrating artistic activity with other forms of meaning-making, and particularly the search for truth. In a number of his writings Gadamer gives attention to the distinctive nature of symbolism when it occurs ...