![]()

1

The First Revolution Writing

The Invention of Writing

With the cultivation of grains and the domestication of animals, tribes of hunters, fishers, and gatherers could put down roots in stable communities, expecting to be able to feed themselves from year to year. In alluvial valleys and deltas, the nomads settled down to the more certain life of farmers. So it was in the Nile delta of Egypt, along the banks of the Indus in northwest India, the Yellow in China, and the Tigris and Euphrates in the part of Mesopotamia that is now Iraq, where the Sumerians once dwelled. Communities grew, conquests united them, governments followed, and commerce spread. Priests required tribute to the gods and tax collectors came calling for much of what was left. All of this getting and giving required writing and record keeping.

On what medium were kept all these records, these calendars and contracts, these land deeds and calculations? To be practical the medium had to be transportable, storable, reasonably permanent, readily made, and cheap. The writing had to be fixed, so a contract, government document, or religious proclamation could not be altered. The writers of documents would get what they needed, for even at this early stage of history, the requirements of the users were driving the technology. Writing would be the foundation of progress. The tools themselves were ordinary, humble things. What ancient peoples eventually did with them was not.

Primeval Chinese ku-wan—gesture pictures—preceded pictographs, the picture symbols that first appeared in Western Asia. Native American tribes notched or painted sticks to convey messages. In South America, Incas knotted colored quipu cords to keep complex records. Aside from portability, however, these media were of limited use.

Writing on Clay

The Chauvet cave paintings recently discovered in France are 30,000 years old and those of Lascaux and Altamira perhaps half that old. But we must look to the Fertile Crescent, particularly to Mesopotamia, for the long trek to reproducing and storing spoken language, which began about 8,000 B.C. in Sumer. Small clay triangles, spheres, cones, and other tokens were molded to represent sheep, measures of grain, jars of oil, and other trading goods. These tokens served a community as a means of keeping track of goods for the purpose of pooling and redistributing the community’s resources.1 As status symbols for the elite members of the community, they were sometimes placed in burial sites. The tokens also indicated gifts brought to the temple for the gods, or brought to a ruler as tribute, or yielded with the best possible grace to the tax gatherer.

The shape of the token carried its meaning. Dozens of different clay tokens aided the accounting over an astonishing period of 5,000 years.2 Starting about 3,700 B.C., the tokens were placed in hollow clay balls, a kind of envelope, for storage. It may have been frustrating that, once the tokens had been sealed inside the ball, there was no way to determine what was inside without cracking the ball open. Sumerian accountants figured out that they could identify the contents of the ball either by fixing an identical token set into the ball’s soft clay surface or leaving an impression by pressing each token against the surface before it hardened. The next step toward writing was taken by scratching a representation of the token in the clay instead of impressing the actual token. In surviving specimens in the world’s museums, the shapes of the representation do not match the tokens, indicating an important step toward abstract thinking.3 Because the outside markings carried the meaning, there was really no need to stuff the actual tokens inside a hollow ball, nor was there really any need for the ball itself. Without the tokens, the ball could be flattened to the shape of a tablet that bore all the information anyone needed.

Sumerians also engraved pieces of stone or metal to make seals that, when pressed on the clay of a wine jar, announced its ownership. The stamped seal gave way to the cylinder seal, which was rolled over the wet clay. As it rolled along it reproduced a pattern, a forerunner of the cylinder press of our own era.

Advancing Knowledge

About 3100 B.C., the Sumerians invented numerals, separating the symbol for sheep from the number of sheep. So, some researchers believe, both writing and mathematics evolved together. The earliest Sumerian writings were pictographs, simple drawings of objects. Archaeological diggings at Uruk showed that the Sumerians advanced to ideographic writing, in which an image or symbol might stand for one or more objects; a symbol could also represent a concept. Writing developed into a tool that was able to communicate ideas. About the time that the Sumerians invented numerals, they advanced an additional step with phonetic writing, where the symbol meant the sound of a consonant and a vowel, thus combining the written and spoken language. The Sumerians had invented syllabic writing, somewhat like the modern Japanese kana, not yet an alphabet.

Babylon carried its predecessor Sumerian and Akkadian cultures to new heights. Writing, as the Sumerians and the Akkadians did on clay tablets with cuneiform script, plus a syllabary (each symbol is a syllable, usually a consonant and a vowel) that they interspersed with ideographs,4 the Babylonians recorded abstract religious and philosophical thoughts. They classified plants, animals, metals, and rocks. They advanced knowledge in mathematics, astronomy, and engineering. However, unlike the analytical thinking of the later Greeks, the Babylonians mixed logic with superstition and myth.5

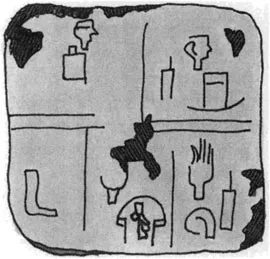

Figure 1.1 Pictographs carved into clay tablets enabled peoples of the ancient Near East to keep records.

The most famous of all documents in Mesopotamian history, Hammurabi’s legal code, written during the eighteenth century B.C. in the Semitic Babylonian language, was carved on stelae and placed in temples. Among the nearly 300 laws by this “Mighty King of the Four Quarters of the World,” was a reformed, standard writing system for the lands he had conquered, extending from present day Syria to Iran.

Writing that began in Sumer was later adopted by Egypt. How it traveled there is not known. Perhaps it moved along the trade route that had existed since prehistoric times.6 Hieroglyphics, serving mostly for sacred writing, were inscribed on Egyptian tomb walls and on pottery. Hieroglyphs were used also for recording each ruler’s version of history, not as a way for ordinary mortals to communicate with each other. Egyptian priests formulated a second written language, hieratic, for religious writing. From hieratic, a secular version, demotic, was conceived for daily use such as record keeping and correspondence. It was a combination of picture and phonetic writing, yet still not an alphabet. With demotic writing, the Egyptians had developed a writing system that brought written communication to a slightly wider segment of society, but it was still complicated and difficult to master, and it was by no means mass communication.

The next step up the evolutionary ladder of writing beyond the symbolic ideographs would be an integrated system of symbols for both written and spoken language. In a word, an alphabet. Neither the Sumerians nor the Chinese nor the Egyptians, for all their innovations in the uses of writing, had produced the simple, practical system in which one written symbol stands for one spoken sound, so a combination of visible symbols represents what is spoken aloud. The next step would be the phonetic alphabet.

Skin and Bones and Papyrus

Animal skins and bones, palm leaves and oak tree bark, wood and wax, metal and stone, seashells and pottery, silk and cotton, jade and ivory from elephant tusks have all been used to store humankind’s memory.

Other writing media included brass tablets and sheets of leather. Homer’s Iliad speaks of messages written on wood. In Roman times, wax coated the wood. That permitted reuse, as the wax could be warmed and smoothed over, an early recycling program. The reply to a letter might be written on the same letter while the messenger waited. Officials in Julius Caesar’s government used such wax tablets to provide a daily bulletin exhibited in the Forum; the Acta Diurna was a precursor to newspapers.

The familiar vocabulary of the written word began to take shape. Pliny speaks of early writing on leaves and tree bark. From the practice of writing on palm leaves comes our use of leaf as a page of a book. The Latin word liber, referring to the inner bark of trees, gives us library. From the Anglo-Saxon boc, also meaning bark, we get book. The word volume derives from the Latin word for revolve; papyrus scrolls were read by unrolling them. The word paper itself comes from the word papyrus. The Greek word for papyrus was byblos, after the Phœnicians city of Byblos, home of sea traders who carried the bales of papyrus to the Greek cities. From byblos comes the word bible, meaning book or books.

Across the ancient Near East from Sumer to Egypt, common, familiar clay was finding use as a writing medium. The clay was sometimes shaped as flat tablets, sometimes as octagonal cylinders. Moses received the Ten Commandments on “tablets of stone,” which some scholars think were actually sun-dried clay. Historical records might be preserved in books consisting of a series of tablets varying in size from one to twelve inches square.

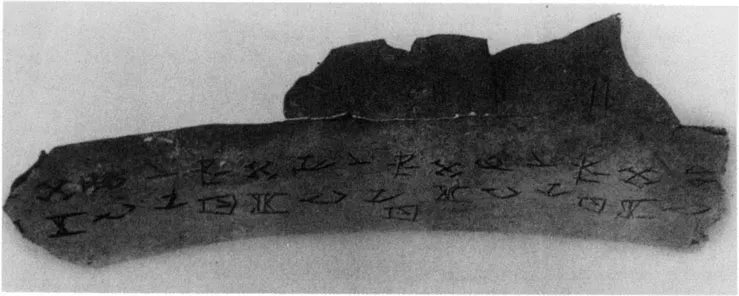

Figure 1.2 Bone inscribed with questions and answers was used to tell the future during the Shang dynasty in China, 1760-1122 B.C.

Ink and inking tools had evolved for untold centuries. Common soot such as collects on pots was mixed with water and some vegetable gum like plant sap to produce a serviceable ink. A reed cut to a point or a brush of hair from a braying animal served as a pen.

Systematic written language began with the Sumerians, who used reeds to scratch marks on tablets of clay. To solve the sticky problem that a reed scratching into wet clay will pull the clay up as it is withdrawn, they designed a writing tool with a wedge tip, resulting in the writing we know as cuneiform. Hardened in fire or the sun’s heat, thousands of these clay tablets have survived to this day, more durable than paper.

Although the medium of clay offered permanent writing and record keeping, plus widespread availability, its disadvantages of inconvenience and weight limited its value. The makers and keepers of records required something different, a medium that ideally was plentiful, cheap, lightweight, and reasonably durable in the short run.

Papyrus in Egypt

Ancient Egyptians found it in the Nile river delta, the reed called papyrus, growing 10 feet high along its banks. From it, peasants constructed boats and huts. It would also prove to be what Durant whimsically termed “the very stuff (and nonsense)” of which civilization was made.7 Workers split the reeds into thin strips, placed one layer crosswise over another in close-set rows, hammered them gently for a couple of hours, and let them dry in the sun. A sea-she...